The study results, published today in the journal Cell, revolve around iPSCs, which since their 2006 discovery have enabled researchers to coax mature (fully differentiated) bodily cells (e.g. skin cells) to become like embryonic stem cells. Such cells are pluripotent, able to become many cell types as they multiply and differentiate to form tissues. The iPSCs can then be converted again as needed into differentiated cells such as heart muscle, nerve cells, bone, etc.

While some seek to use iPSCs as replacements for cells compromised by disease, the new Mount Sinai study sought to determine if they could serve as an accurate model of genetic disease "in a dish." In this context, the dish stands for a self-renewing, unlimited supply of iPSCs or a cell line - which enables in-depth study of disease versions driven by each person's genetic differences. When matched with patient records, iPSCs and iPSC-derived target cells may be able to predict a patient's prognosis and whether or not a given drug will be effective for him or her.

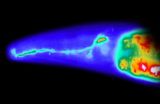

In the current study, skin cells from patient with and without disease were turned into patient-specific iPSC lines, and then differentiated into bone-making cells where both rare and common bone cancers start. This new bone cancer model does a better job than previously used mouse or cellular models of "recapitulating" the features of bone cancer cells driven by key genetic changes.

"Our study is among the first to use induced pluripotent stem cells as the foundation of a model for cancer," said lead author Dung-Fang Lee, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Developmental and Regenerative Biology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. "This model, when combined with a rare genetic disease, revealed for the first time how a protein known to prevent tumor growth in most cases, p53, may instead drive bone cancer when genetic changes cause too much of it to be made in the wrong place."

Rare Disease Sheds Light on Common Disease The Mount Sinai disease model research is based on the fact that human genes, the DNA chains that encode instructions for building the body's structures and signals, randomly change all the time. As part of evolution, some code changes, or mutations, make no difference, some confer advantages, and others cause disease. Beyond inherited mutations that contribute to cancer risk, the wrong mix of random, accumulated DNA changes in bodily (somatic) cells as we age also contributes to cancer risk.

The current study focused on the genetic pathways that cause a rare genetic disease called Li-Fraumeni Syndrome or LFS, which comes with high risk for many cancers in affected families. A common LFS cancer type is osteosarcoma (bone cancer), with many diagnosed before the age of 30. Beyond LFS, osteosarcoma is the most common type of bone cancer in all children, and after leukemia, the second leading cause of cancer death for them.

Importantly, about 70 percent of LFS families have a mutation in their version of the gene TP53, which is the blueprint for protein p53, well known by the nickname "the tumor suppressor." Common forms of osteosarcoma, driven by somatic versus inherited mutations, have also been closely linked by past studies to p53 when mutations interfere with its function.

Rare genetic diseases like LFS are good study models because they tend to proceed from a change in a single gene, as opposed to many, overlapping changes seen in more related common diseases, in this case more common, non-inherited bone cancers. The LFS-iPSC based modeling highlights the contribution of p53 alone to osteosarcoma.

Combining iPSC lines, and bone cancer driven by p53 mutations in LFS patients, the research team revealed for the first time that the LFS bone cancer results from an overactive p53 gene. Too much p53 in bone-making cells called osteoblasts dials down a gene, H19, and a related protein, decorin, that would otherwise help stem cells mature (differentiate) to become normal osteoblasts.

The inability of cells to differentiate makes them vulnerable to genetic mistakes that drive cancer, since more "stemness" means a tendency toward rapid, abnormal growth seen in tumors. One tragic feature of osteosarcoma is the rapid, error-prone production of weaker bone by cancerous bone-making cells, where a young person surprisingly breaks a bone to reveal undiagnosed, advanced cancer.

The research team found that the H19 gene may control a network of interconnected genes that fine-tunes the balance between cell growth and resistance to growth. Decorin is a protein that is part of connective tissue like bone, but that also plays a signaling role, interacting with growth factors to slow the rate that cells divide and multiply, unless turned off by too much p53.

"Our experiments showed that restoring H19 expression hindered by too much p53 restored "protective differentiation" of osteoblasts to counter events of tumor growth early on in bone cancer," said co-author, Ihor Lemischka, PhD, Director of The Black Family Stem Cell Institute within the Icahn School of Medicine. "The work has implications for the future treatment or prevention of LFS-associated osteosarcoma, and possibly for all forms of bone cancer driven by p53 mutations, with H19 and p53 established now as potential targets for future drugs."

INFORMATION:

Along with Drs. Lee and Lemischka, study authors Jie Su, Huen Suk Kim, Betty Chang, Dmitri Papatsenko, Ye Yuan, Julian Gingold, Henia Darr and Christoph Schaniel made important contributions within the Department of Developmental and Regenerative Biology, and The Black Family Stem Cell Institute, both within the Icahn School of Medicine. Drs. Schaniel and Lemischka are also faculty within the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and the Department of Pharmacology and Systems Therapeutics. Also making important contributions were study authors Ruiying, Zhao, Weiya Xia and Mien-Chie Hung in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Oncology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and Razmik Mirzayans in the Department of Oncology, University of Alberta.

This research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (5R01GM078465 and K99CA181496), the Empire State Stem Cell Fund through New York State Department of Health (NYSTEM) (C024176 and C024410), The University of Texas MD Anderson-China Medical University and Hospital Sister Institution Fund, and The National Breast Cancer Foundation.

About the Mount Sinai Health System

The Mount Sinai Health System is an integrated health system committed to providing distinguished care, conducting transformative research, and advancing biomedical education. Structured around seven member hospital campuses and a single medical school, the Health System has an extensive ambulatory network and a range of inpatient and outpatient services--from community?based facilities to tertiary and quaternary care.

The System includes approximately 6,600 primary and specialty care physicians, 12?minority?owned free?standing ambulatory surgery centers, over 45 ambulatory practices throughout the five boroughs of New York City, Westchester, and Long Island, as well as 31 affiliated community health centers. Physicians are affiliated with the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which is ranked among the top 20 medical schools both in National Institutes of Health funding and by U.S. News & World Report.

For more information, visit http://www.mountsinai.org, or find Mount Sinai on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.