Brain activity in infants predicts language outcomes in autism spectrum disorder

2015-04-09

(Press-News.org) Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can produce strikingly different clinical outcomes in young children, with some having strong conversation abilities and others not talking at all. A study published by Cell Press April 9th in Neuron reveals the reason: At the very first signs of possible autism in infants and toddlers, neural activity in language-sensitive brain regions is already similar to normal in those ASD toddlers who eventually go on to develop good language ability but nearly absent in those who later have a poor language outcome.

"Why some toddlers with ASD get better and develop good language and others do not has been a mystery that is of the utmost importance to solve," says senior author Eric Courchesne, co-director of the UC San Diego Autism Center, where the study was designed and conducted. "Discovering the early neural bases for these different developmental trajectories now opens new avenues to finding causes and treatments specific to these two very different subtypes of autism."

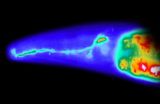

The researchers studied 60 ASD and 43 non-ASD infants and toddlers using the natural sleep functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) method developed by the UCSD Autism Center investigators to record brain activity in the participants as they listened to excerpts from children's stories. All toddlers were clinically followed until early childhood to make a final determination of which ones eventually had good versus poor language outcomes.

In ASD, good language outcomes by early childhood were preceded by normal patterns of neural activity in language-sensitive brain regions, including superior temporal cortex, during infant and toddler ages. By contrast, ASD children with poor language outcomes showed very little activity in superior temporal cortex when they were toddlers or infants.

"Our study is important because it's one of the first large-scale studies to identify very early neural precursors that help to differentiate later emerging and clinically relevant heterogeneity in early language development in ASD toddlers," says first author Michael Lombardo of the University of Cyprus.

The researchers also found that, when combined with behavioral tests, these striking early neural differences may help predict later language outcome by early childhood. The prognostic accuracy of the combined neural and behavioral measures was 80%, compared with 68% for each measure alone. "One of the first things parents of a toddler with ASD want to know is what lies ahead for their child," says co-author Karen Pierce, also co-director of the UC San Diego Autism Center. "These findings open insight into the first steps that lead to different clinical and treatment outcomes, and in the future, one can imagine clinical evaluation and treatment planning incorporating multiple accurate behavioral and medical prognostic assessments. That would be a huge practical benefit for families."

Moving forward, the researchers will further investigate the early neural functional substrates that precede and underlie language and social heterogeneity in ASD. They also plan to test the idea that activation, or its absence, in language cortex predicts treatment responsiveness in toddlers with ASD. Moreover, future research on the molecular underpinnings of variable clinical outcomes in individuals with ASD could pave the way for the development of novel pharmacological interventions. "Understanding that there are discrete subgroups of early developing ASD that are distinguished by developmental behavioral trajectories, neural underpinnings, and brain-behavioral relationships, really lays the groundwork for a whole range of really fruitful directions," Lombardo says.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Foundation for Autism Research, and fellowships from Jesus College, Cambridge and the British Academy.

Neuron, Lombardo et al.: "Different functional neural substrates for good and poor language outcome in autism" http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.023

Neuron, published by Cell Press, is a bimonthly journal that has established itself as one of the most influential and relied upon journals in the field of neuroscience and one of the premier intellectual forums of the neuroscience community. It publishes interdisciplinary articles that integrate biophysical, cellular, developmental, and molecular approaches with a systems approach to sensory, motor, and higher-order cognitive functions. For more information, please visit http://www.cell.com/neuron. To receive media alerts for Neuron or other Cell Press journals, please contact press@cell.com.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-04-09

Using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), a team led by Mount Sinai researchers has gained new insight into genetic changes that may turn a well known anti-cancer signaling gene into a driver of risk for bone cancers, where the survival rate has not improved in 40 years despite treatment advances.

The study results, published today in the journal Cell, revolve around iPSCs, which since their 2006 discovery have enabled researchers to coax mature (fully differentiated) bodily cells (e.g. skin cells) to become like embryonic stem cells. Such cells are pluripotent, able ...

2015-04-09

LA JOLLA--If you had 10 chances to roll a die, would you rather be guaranteed to receive $5 for every roll ($50 total) or take the risk of winning $100 if you only roll a six?

Most animals, from roundworms to humans, prefer the more predictable situation when it comes to securing resources for survival, such as food. Now, Salk scientists have discovered the basis for how animals balance learning and risk-taking behavior to get to a more predictable environment. The research reveals new details on the function of two chemical signals critical to human behavior: dopamine--responsible ...

2015-04-09

A genetic mutation associated with an increased risk of developing eating disorders in humans has now been found to cause several behavioral abnormalities in mice that are similar to those seen in people with anorexia nervosa. The findings, published online April 9 in Cell Reports, may point to novel treatments to reverse behavioral problems associated with disordered eating.

"It's been known for a long time that about 50% to 70% of the risk of getting an eating disorder was inherited, but the identity of the genes that mediate this risk is unknown," explains senior author ...

2015-04-09

Two types of touch information -- the feel of an object and the position of an animal's limb -- have long been thought to flow into the brain via different channels and be integrated in sophisticated processing regions. Now, with help from a specially devised mechanical exoskeleton that positioned monkeys' hands in different postures, Johns Hopkins researchers have challenged that view. In a paper published in the April 22 issue of Neuron, they present evidence that the two types of information are integrated as soon as they reach the brain by sense-processing brain cells ...

2015-04-09

It turns out sea turtles, even at a tender 6-18 months of age, are very active swimmers. They don't just passively drift in ocean currents as researchers once thought. NOAA and University of Central Florida researchers say it's an important new clue in the sea turtle "lost years" mystery. Where exactly turtles travel in their first years of life, before returning to coastal areas as adults to forage and reproduce, has puzzled scientists for decades.

"All species of sea turtles are endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act; knowing their distribution is ...

2015-04-09

Building on their discovery of a gene linked to eating disorders in humans, a team of researchers at the University of Iowa has now shown that loss of the gene in mice leads to several behavioral abnormalities that resemble behaviors seen in people with anorexia nervosa.

The team, led by Michael Lutter, MD, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry in the UI Carver College of Medicine, found that mice that lack the estrogen-related receptor alpha (ESRRA) gene are less motivated to seek out high-fat food when they are hungry and have abnormal social interactions. The effect ...

2015-04-09

WASHINGTON -- Facial plastic surgery may do more than make you look youthful. It could change -- for the better -- how people perceive you. The first study of its kind to examine perception after plastic surgery finds that women who have certain procedures are perceived as having greater social skills and are more likeable, attractive and feminine.

The study is not superficial -- the importance of facial appearance is rooted in evolution and studies suggest that judging a person based on his or her appearance boils down to survival. The results were published online ...

2015-04-09

Facial rejuvenation surgery may not only make you look younger, it may improve perceptions of you with regard to likeability, social skills, attractiveness and femininity, according to a report published online by JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery.

The relationship between facial features and personality traits has been studied in other science fields, but it is lacking in the surgical literature, according to the study background.

Michael J. Reilly, M.D., of the MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, and coauthors measured the changes in personality perception ...

2015-04-09

Axillary lymph node evaluation is performed frequently in women with ductal carcinoma in situ breast cancer, despite recommendations generally against such an assessment procedure in women with localized cancer undergoing breast-conserving surgery, according to a study published online by JAMA Oncology.

While axillary lymph node evaluation is the standard of care in the surgical management of invasive breast cancer, a benefit has not been demonstrated in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). For women with invasive breast cancer, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) replaced ...

2015-04-09

LAWRENCE -- A team of scientists at the University of Kansas has pinpointed six chemical compounds that thwart HuR, an "oncoprotein" that binds to RNA and promotes tumor growth.

The findings, which could lead to a new class of cancer drugs, appear in the current issue of ACS Chemical Biology.

"These are the first reported small-molecule HuR inhibitors that competitively disrupt HuR-RNA binding and release the RNA, thus blocking HuR function as a tumor-promoting protein," said Liang Xu, associate professor of molecular biosciences and corresponding author of the paper.

The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Brain activity in infants predicts language outcomes in autism spectrum disorder