(Press-News.org) URBANA, Ill. - Two University of Illinois food scientists have learned that understanding and manipulating porosity during food manufacturing can affect a food's health benefits.

Youngsoo Lee reports that controlling the number and size of pores in processed foods allows manufacturers to use less salt while satisfying consumers' taste buds. Pawan Takhar has found that meticulously managing pore pressure in foods during frying reduces oil uptake, which results in lower-fat snacks without sacrificing our predilection for fried foods' texture and taste.

Both scientists are experts in food engineering and professors in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences' Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition.

Regarding salt, Lee said, "Six in 10 American adults either have high blood pressure or are on the borderline of this diagnosis largely because they eat too much salt. Overconsuming salt is also associated with the development and severity of cardiovascular and bone diseases, kidney stones, gastric cancer, and asthma."

Because 70 percent of the salt Americans consume comes from processed foods, Lee began to study the relationship between the microstructural properties of these foods and the way salt is released when it is chewed.

"Much of the salt that is added to these foods is not released in our mouths where we can taste it, and that means the rest of the salt is wasted," he said. "We wanted to alter porosity in processed food, targeting a certain fat-protein emulsion structure, to see if we could get more of the salt released during chewing. Then food manufacturers won't have to add as much salt as before, but the consumer will taste almost the same amount of saltiness."

Increasing porosity also changed the way the foods broke apart when they were chewed, exposing more surface area and increasing saltiness, he said.

"When foods crumble easily, we further reduce the amount of salt that is needed. Changing the number or size of pores in the food's surface can help us to accomplish this," he said.

Takhar said that his porous media approach to understanding the behavior of water, oil, and gas during frying will help create strategies that optimize the frying process, reduce oil uptake, and produce lower-fat foods.

The articles Takhar publishes in academic journals feature page after page of complex mathematical equations that describe the physics involved in the transport of fluids and in textural changes in foods. These equations then guide the simulations that he performs in his laboratory.

"Frying is such a complicated process involving more than 100 equations. In a matter of seconds, when you put the food in the fryer, water starts evaporating, vapors form and escape the surface, oil penetration starts, and heat begins to rise while at the same time there's evaporative cooling off at different points in the food. Some polymers in the food matrix may also change their state, and chemical reactions can occur. It's not an easy set of changes to describe," he said.

Within 40 seconds of frying, the texture of gently fried processed foods like crackers is fully developed, the scientist said. "That's the cracker's peak texture. Any longer and you're just allowing more oil to penetrate the food.

"A lot of frying research has focused on capillary pressure in the oil phase of the process, but we have found that capillary pressure in the water phase also critically affects oil uptake," Takhar said.

Capillary pressure makes overall pore pressure negative, and that negative pressure tends to suck oil from inside. His simulations show when that pressure is becoming more negative.

"The trick is to stop when pore pressure is still positive (or less negative)--that is, when oil has had less penetration. Of course, other variables such as moisture level, texture, taste, and structure formation, must be monitored as well. It's an optimization problem," he noted.

When this exquisite balance is achieved, lower-fat, healthier fried foods are the result, he added.

INFORMATION:

"Temporal Sodium Release Related to Gel Microstructural Properties--Implications for Sodium Reduction" was published in a recent issue of Journal of Food Science. Lee and Wan-Yuan Kuo are co-authors of the study, which will continue to be funded by USDA. "Modeling Multiscale Transport Mechanisms, Phase Changes, and Thermomechanics during Frying" was published in a recent issue of Food Research International. Co-authors are Takhar and Harkirat S. Bansal of the U of I and Jirawan Maneerote of Kasetsart University in Bangkok, Thailand. The Takhar study was funded by USDA and the Royal Thai Government.

BOSTON (April 9, 2015)- Making small, consistent changes to the types of protein- and carbohydrate-rich foods we eat may have a big impact on long-term weight gain, according to a new study led by researchers at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science & Policy at Tufts University. The results were published on-line this week in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

Based on more than 16 years of follow-up among 120,000 men and women from three long-term studies of U.S. health professionals, the authors first found that diets with a high glycemic load (GL) from ...

The one common element in recent weather has been oddness. The West Coast has been warm and parched; the East Coast has been cold and snowed under. Fish are swimming into new waters, and hungry seals are washing up on California beaches.

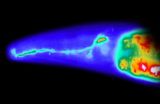

A long-lived patch of warm water off the West Coast, about 1 to 4 degrees Celsius (2 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal, is part of what's wreaking much of this mayhem, according to two University of Washington papers to appear in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union.

"In the fall of 2013 and ...

April 9, 2015 - A new University of Utah study is the first to provide clear insight into contributors to suicide risk among military personnel and veterans who have deployed.

The study, published today in the journal Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, found that exposure to killing and death while deployed is connected to suicide risk. Previous studies that looked solely at the relationship between deployment and suicide risk without assessing for exposure to killing and death have shown inconsistent results.

"Many people assume that deployment equals exposure ...

When black holes tango, one massive partner spins head over heels (or in this case heels over head) until the merger is complete, said researchers at Rochester Institute of Technology in a paper published in Physical Review Letters.

This spin dynamic may affect the growth of black holes surrounded by accretion disks and alter galactic and supermassive binary black holes, leading to observational effects, according to RIT scientists Carlos Lousto and James Healy.

The authors of the study will present their findings at the American Physical Society meeting in Baltimore ...

The RapidScat instrument that flies aboard the International Space Station (ISS) provided data about Tropical Cyclone Joalane's surface winds that showed how the strongest sustained winds consolidated as the tropical cyclone intensified and developed an eye. As of April 9, warnings were in effect at Rodrigues Island in the Southern Indian Ocean as Joalane approached.

RapidScat measured the surface winds within Tropical Cyclone Joalane late on April 7 and on April 8, revealing that the strongest winds consolidated over a 24 hour period. RapidScat measured Joalane's winds ...

Outbreaks of leukemia that have devastated some populations of soft-shell clams along the east coast of North America for decades can be explained by the spread of cancerous tumor cells from one clam to another. Researchers call the discovery, reported in the Cell Press journal Cell on April 9, 2015, "beyond surprising."

"The evidence indicates that the tumor cells themselves are contagious--that the cells can spread from one animal to another in the ocean," said Stephen Goff of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Columbia University. "We know this must be true because ...

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can produce strikingly different clinical outcomes in young children, with some having strong conversation abilities and others not talking at all. A study published by Cell Press April 9th in Neuron reveals the reason: At the very first signs of possible autism in infants and toddlers, neural activity in language-sensitive brain regions is already similar to normal in those ASD toddlers who eventually go on to develop good language ability but nearly absent in those who later have a poor language outcome.

"Why some toddlers with ASD get ...

Using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), a team led by Mount Sinai researchers has gained new insight into genetic changes that may turn a well known anti-cancer signaling gene into a driver of risk for bone cancers, where the survival rate has not improved in 40 years despite treatment advances.

The study results, published today in the journal Cell, revolve around iPSCs, which since their 2006 discovery have enabled researchers to coax mature (fully differentiated) bodily cells (e.g. skin cells) to become like embryonic stem cells. Such cells are pluripotent, able ...

LA JOLLA--If you had 10 chances to roll a die, would you rather be guaranteed to receive $5 for every roll ($50 total) or take the risk of winning $100 if you only roll a six?

Most animals, from roundworms to humans, prefer the more predictable situation when it comes to securing resources for survival, such as food. Now, Salk scientists have discovered the basis for how animals balance learning and risk-taking behavior to get to a more predictable environment. The research reveals new details on the function of two chemical signals critical to human behavior: dopamine--responsible ...

A genetic mutation associated with an increased risk of developing eating disorders in humans has now been found to cause several behavioral abnormalities in mice that are similar to those seen in people with anorexia nervosa. The findings, published online April 9 in Cell Reports, may point to novel treatments to reverse behavioral problems associated with disordered eating.

"It's been known for a long time that about 50% to 70% of the risk of getting an eating disorder was inherited, but the identity of the genes that mediate this risk is unknown," explains senior author ...