INFORMATION:

Journal Reference:

Wen Yang, Vincent R. Sherman, Bernd Gludovatz, Eric Schaible, Polite Stewart, Robert O. Ritchie, Marc A. Meyers. On the tear resistance of skin. Nature Communications, 2015; 6: 6649 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7649

Engineers elucidate why skin is resistant to tearing

2015-04-13

(Press-News.org) Skin is remarkably resistant to tearing and a team of researchers from the University of California, San Diego and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory now have shown why.

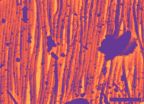

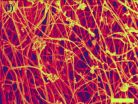

Using powerful X-ray beams and electron microscopy, researchers made the first direct observations of the micro-scale mechanisms that allow skin to resist tearing. They identified four specific mechanisms in collagen, the main structural protein in skin tissue, that act together to diminish the effects of stress: rotation, straightening, stretching, and sliding. Researchers say they hope to replicate these mechanisms in synthetic materials to provide increased strength and in better resistance to tearing.

"Collagen fibrils and fibers rotate, straighten, stretch and slide to carry load and reduce the stresses at the tip of any tear in the skin," said Berkeley Lab's Robert Ritchie, co-leader of this study with Marc Meyers, a professor of mechanical engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. "The movement of the collagen acts to effectively diminish stress concentrations associated with any hole, notch or tear."

"The mechanistic understanding we've identified in skin could be applied to the improvement of artificial skin, or to the development of thin film polymers for applications such as flexible electronics," Ritchie said.

Ritchie and Meyers published their results in the March 31 issue of Nature Communication. The other authors of the study are Wen Yang, Vincent Sherman, Bernd Gludovatz, Eric Schaible and Polite Stewart.

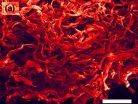

Skin consists of three layers -- the epidermis, dermis and endodermis. Mechanical properties are largely determined in the dermis, which is the thickest layer and is made up primarily of collagen and elastin proteins. "Collagen is by far the most important protein in the skin structure because it controls its mechanical response," said Yang, who mechanically tested skin and other natural materials for the study.

The research team began their work by establishing that a tear in the skin does not propagate or induce fracture, unlike other materials such as bone or tooth dentin, which are composed of mineralized collagen fibrils. Instead, the tearing or notching of skin triggers structural changes in the collagen fibrils of the dermis layer to reduce stress concentration. Initially, these collagen fibrils are curvy and highly disordered. However, in response to a tear, they rearrange themselves in the direction in which the skin is being stressed, and prevent failure through rotation, straightening, stretching, sliding and delamination prior to fracturing.

"The rotation mechanisms recruit collagen fibrils into alignment with the tension axis at which they are maximally strong or can accommodate shape change," says Meyers. "Straightening and stretching allow the uptake of strain without much stress increase, and sliding allows more energy dissipation during inelastic deformation. This reorganization of the fibrils is responsible for blunting the stress at the tips of tears and notches."

This new study of the skin is part of an on-going collaboration between Ritchie and Meyers to examine how nature achieves specific properties through architecture and structure. After its online publication, the study immediately captured the attention of the public and researchers alike. Five days after it was released, it had been picked up by a number of news outlets.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Moffitt develops new method to characterize the structure of a protein that promotes tumor growth

2015-04-13

TAMPA, Fla. - Moffitt Cancer Center researchers have developed a new method to identify a previously unknown structure in a protein called MDMX. MDMX is a crucial regulatory protein that controls p53 - one of the most commonly mutated genes in cancer.

Known as the tumor suppressor gene, p53 protects the body from cancer development by ensuring that DNA remains intact and does not have mutations. If p53 senses DNA damage, it can either stimulate the cells to repair its DNA, or cause cells to stop growing and undergo cell death. Because of its functions, p53 is often ...

Chimpanzees show ability to plan route in computer mazes, research finds

2015-04-13

ATLANTA--Chimpanzees are capable of some degree of planning for the future, in a manner similar to human children, while some species of monkeys struggle with this task, according to researchers at Georgia State University, Wofford College and Agnes Scott College.

Their findings were published on March 23 in the Journal of Comparative Psychology.

The study assessed the planning abilities of chimpanzees, two monkey species (rhesus macaques and capuchin monkeys) and human children (ages 28 to 66 months old) using a computerized game-like program that presented 100 unique ...

Improving work conditions increases parents' time with their children

2015-04-13

A workplace intervention designed to reduce work-family conflict gave employed parents more time with their children without reducing their work time.

"These findings may encourage changes in the structure of jobs and culture of work organizations to support families," said Kelly Davis, research assistant professor of human development and family studies.

The research is part of the Work, Family and Health Network's evaluation of the effects of a workplace intervention designed to reduce work-family conflict by increasing both employees' control over their schedule ...

Study finds emergency departments may help address opioid overdose, education

2015-04-13

(Boston) - Emergency departments (ED) provide a promising venue to address opioid deaths with education on both overdose prevention and appropriate actions in a witnessed overdose. In addition, ED's have the potential to equip patients with nasal naloxone rescue kits as part of this effort.

These findings are from a study published in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, and is the first study to demonstrate the feasibility of ED-based opioid overdose prevention education and naloxone distribution to trained laypersons, patients and their social network.

In ...

Gold by special delivery intensifies cancer-killing radiation

2015-04-13

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Researchers from Brown University and the University of Rhode Island have demonstrated a promising new way to increase the effectiveness of radiation in killing cancer cells.

The approach involves gold nanoparticles tethered to acid-seeking compounds called pHLIPs. The pHLIPs (pH low-insertion peptides) home in on high acidity of malignant cells, delivering their nanoparticle passengers straight to the cells' doorsteps. The nanoparticles then act as tiny antennas, focusing the energy of radiation in the area directly around the cancer ...

Mechanism outlined by which inadequate vitamin E can cause brain damage

2015-04-13

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Researchers at Oregon State University have discovered how vitamin E deficiency may cause neurological damage by interrupting a supply line of specific nutrients and robbing the brain of the "building blocks" it needs to maintain neuronal health.

The findings - in work done with zebrafish - were just published in the Journal of Lipid Research. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

The research showed that zebrafish fed a diet deficient in vitamin E throughout their life had about 30 percent lower levels of DHA-PC, which is a ...

Pitt cancer virology team reveals new pathway that controls how cells make proteins

2015-04-13

PITTSBURGH, April, 13, 2015 - A serendipitous combination of technology and scientific discovery, coupled with a hunch, allowed University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute (UPCI) researchers to reveal a previously invisible biological process that may be implicated in the rapid growth of some cancers.

The project, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), is described in today's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

"I was so amazed by what I was seeing," said lead author Masahiro Shuda, Ph.D., research assistant professor in Pitt's ...

Mystery of Rett timing explained in MeCP2 binding

2015-04-13

HOUSTON - (April 13, 2015) - For decades, scientists and physicians have puzzled over the fact that infants with the postnatal neurodevelopmental disorder Rett syndrome show symptoms of the disorder from one to two years after birth.

In a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Dr. Huda Zoghbi and her colleagues from Baylor College of Medicine and the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children's Hospital, unravel the mystery by looking at when and how the causal gene involved (methyl-CpG binding protein 2 or MECP2) binds ...

Bacterial raincoat discovery paves way to better crop protection

2015-04-13

Fresh insights into how bacteria protect themselves - by forming a waterproof raincoat - could help develop improved products to protect plants from disease.

Researchers have discovered how communities of beneficial bacteria form a waterproof coating on the roots of plants, to protect them from microbes that could potentially cause plant disease.

Their insights could lead to ways to control this shield and improve its efficiency, which could help curb the risk of unwanted infections in agricultural or garden plants, the team says.

Scientists at the Universities of ...

Meteorites key to the story of Earth's layers: ANU media release

2015-04-13

A new analysis of the chemical make-up of meteorites has helped scientists work out when the Earth formed its layers.

The research by an international team of scientists confirmed the Earth's first crust had formed around 4.5 billion years ago.

The team measured the amount of the rare elements hafnium and lutetium in the mineral zircon in a meteorite that originated early in the solar system.

"Meteorites that contain zircons are rare. We had been looking for an old meteorite with large zircons, about 50 microns long, that contained enough hafnium for precise analysis," ...