INFORMATION:

Link to paper: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1038/ncomms7762

Mapping language in the brain

2015-04-16

(Press-News.org) The exchange of words, speaking and listening in conversation, may seem unremarkable for most people, but communicating with others is a challenge for people who have aphasia, an impairment of language that often happens after stroke or other brain injury. Aphasia affects about 1 in 250 people, making it more common than Parkinson's Disease or cerebral palsy, and can make it difficult to return to work and to maintain social relationships. A new study published in the journal Nature Communications provides a detailed brain map of language impairments in aphasia following stroke.

"By studying language in people with aphasia, we can try to accomplish two goals at once: we can improve our clinical understanding of aphasia and get new insights into how language is organized in the mind and brain," said Daniel Mirman, PhD, an assistant professor in Drexel University's College of Arts and Sciences who was lead author of the study.

The study is part of a larger multi-site research project funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and led by senior author Myrna Schwartz, PhD of the Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute. The researchers examined data from 99 people who had persistent language impairments after a left-hemisphere stroke. In the first part of the study, the researchers collected 17 measures of cognitive and language performance and used a statistical technique to find the common elements that underlie performance on multiple measures.

They found that spoken language impairments vary along four dimensions or factors:

Semantic Recognition: difficulty recognizing the meaning or relationship of concepts, such as matching related pictures or matching words to associated pictures.

Speech Recognition: difficulty with fine-grained speech perception, such as telling "ba" and "da" apart or determining whether two words rhyme.

Speech Production: difficulty planning and executing speech actions, such as repeating real and made-up words or the tendency to make speech errors like saying "girappe" for "giraffe."

Semantic Errors: making semantic speech errors, such as saying "zebra" instead of "giraffe," regardless of performance on other tasks that involved processing meaning.

Mapping the Four Factors in the Brain

Next, the researchers determined how individual performance differences for each of these factors were associated with the locations in the brain damaged by stroke. This procedure created a four-factor lesion-symptom map of hotspots the language-specialized left hemisphere where damage from a stroke tended to cause deficits for each specific type of language impairment. One key area was the left Sylvian fissure: speech production and speech recognition were organized as a kind of two-lane, two-way highway around the Sylvian fissure. Damage above the Sylvian fissure, in the parietal and frontal lobes, tended to cause speech production deficits; damage below the Sylvian fissure, in the temporal lobe, tended to cause speech recognition deficits. These results provide new evidence that the cortex around the Sylvian fissure houses separable neural specializations for speech recognition and production.

Semantic errors were most strongly associated with lesions in the left anterior temporal lobe, a location consistent with previous research findings from these researchers and several other research groups. This finding also made an important comparison point for its opposite factor - semantic recognition, which many researchers have argued critically depends on the anterior temporal lobes. Instead, Mirman and colleagues found that semantic recognition deficits were associated with damage to an area they call a "white matter bottleneck" -- a region of convergence between multiple tracts of white matter that connect brain regions required for knowing the meanings of words, objects, actions and events.

"Semantic memory almost certainly involves a widely distributed neural system because meaning involves so many different kinds of information," said Mirman. "We think the white matter bottleneck looks important because it is a point of convergence among multiple pathways in the brain, making this area a vulnerable spot where a small amount of damage can have large functional consequences for semantic processing."

In a follow-up article soon to be published in the journal Neuropsychologia, Mirman, Schwartz and their colleagues also confirmed these findings with a re-analysis using a new and more sophisticated statistical technique for lesion-symptom mapping.

These studies provide a new perspective on diagnosing different kinds of aphasia, which can have a big impact on how clinicians think about the condition and how they approach developing treatment strategies. The research team at the Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute works closely with its clinical affiliate, the MossRehab Aphasia Center, to develop and test approaches to aphasia rehabilitation that meet the individualized, long-term goals of the patients and are informed by scientific evidence.

According to Schwartz, "A major challenge facing speech-language therapists is the wide diversity of symptoms that one sees in stroke aphasia. With this study, we took a major step towards explaining the symptom diversity in relation to a few primary underlying processes and their mosaic-like representation in the brain. These can serve as targets for new diagnostic assessments and treatment interventions."

Studying the association between patterns of brain injury and cognitive deficits is a classic approach, with roots in 19th century neurology, at the dawn of cognitive neuroscience. Mirman, Schwartz and their colleagues have scaled up this approach, both in terms of the number of participants and the number of performance measures, and combined it with 21st century brain imaging and statistical techniques. A single study may not be able to fully reveal a system as complex as language and brain, but the more we learn, the closer we get to translating basic cognitive neuroscience into effective rehabilitation strategies.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Keep moving, studies advise cancer survivors

2015-04-16

Three or more hours of walking per week can boost the vitality and health of prostate cancer survivors. Men and women who have survived colorectal cancer and are regular walkers as well report lower sensations of burning, numbness, tingling or loss of reflexes that many often experience post-treatment. These are among the findings of two studies published in Springer's Journal of Cancer Survivorship that highlight the benefits of exercise for cancer survivors.

In the first, a group of American researchers led by Siobhan Phillips of Northwestern University weighed up the ...

Bacterial 'memory' targets invading viruses

2015-04-16

One of the immune system's most critical challenges is to differentiate between itself and foreign invaders -- and the number of recognized autoimmune diseases, in which the body attacks itself, is on the rise. But humans are not the only organisms contending with "friendly fire."

Even single-celled bacteria attack their own DNA. What protects these bacteria, permitting them to survive the attacks?

A new study published in Nature by a team of researchers at Tel Aviv University and the Weizmann Institute of Science now reveals the precise mechanism that bacteria's defense ...

Inducing labor at full term not associated with higher C-section rates

2015-04-16

(PHILADELPHIA) - As cesarean section rates continue to climb in the United States, researchers are looking to understand the factors that might contribute. There has been debate in the field about whether non-medically required induction of labor leads to a greater likelihood of C-section, with some studies showing an association and others demonstrating that inductions at full term can actually protect both the mothers and babies. In order to tease apart the evidence, a new analysis pooled the results from five randomized controlled trials including 844 women, and found ...

Wildfires emit more greenhouse gases than assumed in California climate targets

2015-04-16

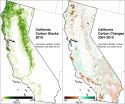

Berkeley - A new study quantifying the amount of carbon stored and released through California forests and wildlands finds that wildfires and deforestation are contributing more than expected to the state's greenhouse gas emissions.

The findings, published online today (Wednesday, April 15), in the journal Forest Ecology and Management, came from a collaborative project led by the National Park Service and the University of California, Berkeley. The results could have implications for California's efforts to meet goals mandated by the state Global Warming Solutions Act, ...

A novel mechanism involved in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

2015-04-16

Researchers at the Angiocardioneurology Department of the Neuromed Scientific Institute for Research, Hospitalisation and Health Care of Pozzilli (Italy), have found, in animal models, that the absence of a certain enzyme causes a syndrome resembling the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The study, published in the international journal EMBO Molecular Medicine, paves the way for a greater understanding of this childhood and adolescent disease, aiming at innovative therapeutic approaches.

Described for the first time in 1845, but came to the fore only in ...

Systems-wide genetic study of blood pressure regulation in the Framingham Heart Study

2015-04-16

HEIDELBERG, 15 April 2015 - A genetic investigation of individuals in the Framingham Heart Study may prove useful to identify novel targets for the prevention or treatment of high blood pressure. The study, which takes a close look at networks of blood pressure-related genes, is published in the journal Molecular Systems Biology.

More than one billion people worldwide suffer from high blood pressure and this contributes significantly to deaths from cardiovascular disease. It is hoped that advances in understanding the genetic basis of how blood pressure is regulated ...

Increasing evidence points to inflammation as source of nervous system manifestations of Lyme disease

2015-04-16

Philadelphia, PA, April 16, 2015 - About 15% of patients with Lyme disease develop peripheral and central nervous system involvement, often accompanied by debilitating and painful symptoms. New research indicates that inflammation plays a causal role in the array of neurologic changes associated with Lyme disease, according to a study published in The American Journal of Pathology. The investigators at the Tulane National Primate Research Center and Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center also showed that the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone prevents many ...

Study: Breastfeeding may prevent postpartum smoking relapse

2015-04-16

New York, NY--While a large number of women quit or reduce smoking upon pregnancy recognition, many resume smoking postpartum. Previous research has estimated that approximately 70% of women who quit smoking during pregnancy relapse within the first year after childbirth, and of those who relapse, 67% resume smoking by three months, and up to 90% by six months.

A new study out in the Nicotine & Tobacco Research indicates the only significant predictor in change in smoking behaviors for women who smoked during pregnancy was in those who breastfed their infant, finding ...

Teaching children in schools about sexual abuse may help them report abuse

2015-04-16

Children who are taught about preventing sexual abuse at school are more likely than others to tell an adult if they had, or were actually experiencing sexual abuse. This is according to the results of a new Cochrane review published in the Cochrane Library today. However, the review's authors say that more research is needed to establish whether school-based programmes intended to prevent sexual abuse actually reduce the incidence of abuse.

It is estimated that, worldwide, at least 1 in 10 girls and 1 in 20 boys experience some form of sexual abuse in childhood. Those ...

New research agenda provides roadmap to improve care for hospitalized older adults

2015-04-16

Older adults with complex medical needs are occupying an increasing number of beds in acute care hospitals, and these patients are commonly cared for by hospitalists with limited formal geriatrics training. These clinicians are also hindered by a lack of research that addresses the needs of the older adult population. A new paper published today in the Journal of Hospital Medicine outlines a research agenda to address these issues.

To help support hospitalists in providing acute inpatient geriatric care, the Society of Hospital Medicine has developed a research agenda ...