(Press-News.org) Bats are masters of flight in the night sky, capable of steep nosedives and sharp turns that put our best aircraft to shame. Although the role of echolocation in bats' impressive midair maneuvering has been extensively studied, the contribution of touch has been largely overlooked. A study published April 30 in Cell Reports shows, for the first time, that a unique array of sensory receptors in the wing provides feedback to a bat during flight. The findings also suggest that neurons in the bat brain respond to incoming airflow and touch signals, triggering rapid adjustments in wing position to optimize flight control.

"This study provides evidence that the sense of touch plays a key role in the evolution of powered flight in mammals," says co-senior study author Ellen Lumpkin, a Columbia University associate professor of dermatology and physiology and cellular biophysics. "This research also lays the groundwork for understanding what sensory information bats use to perform such remarkable feats when flying through the air and catching insects. Humans cannot currently build aircrafts that match the agility of bats, so a better grasp of these processes could inspire new aircraft design and new sensors for monitoring airflow."

Bats must rapidly integrate different types of sensory information to catch insects and avoid obstacles while flying. The contribution of hearing and vision to bat flight is well established, but the role of touch has received little attention since the discovery of echolocation. Recently, co-senior study author Cynthia Moss and co-author Susanne Sterbing-D'Angelo of The Johns Hopkins University discovered that microscopic wing hairs stimulated by airflow, are critical for flight behaviors such as turning and controlling speed. But until now, it was not known how bats use tactile feedback from their wings to control flight behaviors.

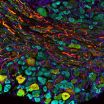

In the new study, the Lumpkin and Moss labs analyzed, for the first time, the distribution of different sensory receptors in the wing and the organization of the wing skin's connections to the nervous system. Compared to other mammalian limbs, the bat wing has a unique distribution of hair follicles and touch-sensitive receptors, and the spatial pattern of these receptors suggests that different parts of the wing are equipped to send different types of sensory information to the brain.

"While sensory cells located between the "fingers" could respond to skin stretch and changes in wind direction, another set of receptors associated with hairs could be specialized for detecting turbulent airflow during flight," says Sterbing-D'Angelo, who also holds an appointment at the University of Maryland.

Moreover, bat wings have a distinct sensory circuitry in comparison to other mammalian forelimbs. Sensory neurons on the wing send projections to a broader and lower section of the spinal cord, including much of the thoracic region. In other mammals, this region of the spinal cord usually receives signals from the trunk rather than the forelimbs. This unusual circuitry reflects the motley roots of the bat wing, which arises from the fusion of the forelimb, trunk, and hindlimb during embryonic development.

"This is important because it gives us insight into how evolutionary processes incorporate new body parts into the nervous system," says first author Kara Marshall of Columbia University. "Future studies are needed to determine whether these organizational principles of the sensory circuitry of the wing are conserved among flying mammals."

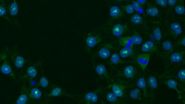

The researchers also found that neurons in the brain responded when the wing was either stimulated by air puffs or touched with a thin filament, suggesting that airflow and tactile stimulation activate common neural pathways.

"Our next steps will be following the sensory circuits in the wings all the way from the skin to the brain. In this study, we have identified individual components of these circuits, but next we would like to see how they are connected in the central nervous system," Moss says. "An even bigger goal will be to understand how the bat integrates sensory information from the many receptors in the wing to create smooth, nimble flight."

INFORMATION:

Cell Reports, Marshall et al.: "Somatosensory Substrates of Flight Control in Bats" http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.001

Cell Reports, published by Cell Press, is a weekly open-access journal that publishes high-quality papers across the entire life sciences spectrum. The journal features reports, articles, and resources that provide new biological insights, are thought-provoking, and/or are examples of cutting-edge research. For more information, please visit http://www.cell.com/cell-reports. To receive media alerts for Cell Reports or other Cell Press journals, contact press@cell.com.

Neuroscientists have perfected a chemical-genetic remote control for brain circuitry and behavior. This evolving technology can now sequentially switch the same neurons - and the behaviors they mediate - on-and-off in mice, say researchers funded by the National Institutes of Health. Such bidirectional control is pivotal for decoding the brain workings of complex behaviors. The findings are the first to be published from the first wave of NIH grants awarded last fall under the BRAIN Initiative.

"With its new push-pull control, this tool sharpens the cutting edge of ...

The feeling of being inside one's own body is not as self-evident as one might think. In a new study from Sweden's Karolinska Institutet, neuroscientists created an out-of-body illusion in participants placed inside a brain scanner. They then used the illusion to perceptually 'teleport' the participants to different locations in a room and show that the perceived location of the bodily self can be decoded from activity patterns in specific brain regions.

The sense of owning one's body and being located somewhere in space is so fundamental that we usually take it for granted. ...

First study to show pattern of telomere changes at multiple time points as cancer develops

Telomeres can look 15 years older in people developing cancer

Pattern suggests when cancer hijacks the cell's aging process

CHICAGO -- A distinct pattern in the changing length of blood telomeres, the protective end caps on our DNA strands, can predict cancer many years before actual diagnosis, according to a new study from Northwestern Medicine in collaboration with Harvard University.

The pattern -- a rapid shortening followed by a stabilization three or four years before ...

Rochester, Minn. -- Over the last decade, numerous studies have shown that many Americans have low vitamin D levels and as a result, vitamin D supplement use has climbed in recent years. Vitamin D has been shown to boost bone health and it may play a role in preventing diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease and other illnesses. In light of the increased use of vitamin D supplements, Mayo Clinic researchers set out to learn more about the health of those with high vitamin D levels. They found that toxic levels are actually rare.

Their study appears in the May issue of ...

LA JOLLA--Stem cells, which have the potential to turn into any kind of cell, offer the tantalizing possibility of generating new tissues for organ replacements, stroke victims and patients of many other diseases. Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have uncovered details about stem cell growth that could help improve regenerative therapies.

While it was known that two key cellular processes--called Wnt and Activin--were needed for stem cells to grow into specific mature cells, no one knew exactly how these pathways worked together. The details of how Wnt and Activin ...

Many human communities want answers about the current status and future of Arctic marine mammals, including scientists who dedicate their lives to study them and indigenous people whose traditional ways of subsistence are intertwined with the fate of species such as ice seals, narwhals, walruses and polar bears.

But there are many unknowns about the current status of 11 species of marine mammals who depend on Arctic sea ice to live, feed and breed, and about how their fragile habitat will evolve in a warming world.

A recently published multinational study attempted ...

AUSTIN, Minn. (4/30/15) - Taking aspirin reduces a person's risk of colorectal cancer, but the molecular mechanisms involved have remained unknown until a recent discovery by The Hormel Institute, University of Minnesota.

Researchers led by The Hormel Institute's Executive Director Dr. Zigang Dong and Associate Director Dr. Ann M. Bode, who co-lead the Cellular & Molecular Biology section, discovered that aspirin might exert its chemopreventive activity against colorectal cancer, at least partially, by normalizing the expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ...

New York, NY (April 30, 2015) - The use of integrative medicine interventions leads to significant improvements in patient activation and patient-reported outcomes in the treatment of chronic pain, depression, and stress, according to a new report released by The Bravewell Collaborative. The findings are based on data collected by the Patients Receiving Integrative Medicine Interventions Effectiveness Registry (PRIMIER), the first-ever patient registry on integrative medicine.

"We are encouraged by these early results, and we see tremendous potential for PRIMIER to provide ...

Philadelphia, April 30, 2015 -- The American College of Physicians (ACP) today released clinical advice aimed at reducing overuse of cervical cancer screening in average risk women without symptoms. "Cervical Cancer Screening in Average Risk Women" is published in Annals of Internal Medicine and lists two concurring organizations: the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Clinical Pathology.

"ACP's advice for cervical cancer screening is designed to maximize the benefits and minimize the harms of testing," said Dr. David Fleming, ...

1. American College of Physicians releases Best Practice Advice for the proper time, test, and interval for cervical cancer screening

ACP's advice is supported by ACOG and endorsed by ASCP

New clinical advice from the American College of Physicians (ACP) aims to reduce overuse of cervical cancer screening in average risk women without symptoms. "Cervical Cancer Screening in Average Risk Women" is published in Annals of Internal Medicine and lists two concurring organizations: the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society for Clinical ...