Redesigned systems may increase access to MRI for patients with implanted medical devices

Massachusetts General-led team uses stealth technology to prevent excess heating of signal-carrying device leads

2015-05-05

(Press-News.org) New technology developed at the Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) may extend the benefits of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to many patients whose access to MRI is currently limited. A redesign of the wire at the core of the leads that carry signals between implanted medical devices and their target structures significantly reduces the generation of heat that occurs when standard wires are exposed to the radiofrequency (RF) energy used in MRI. The novel system is described in a paper published in the online Nature journal Scientific Reports.

"Clinical electrical stimulation systems such as pacemakers and deep-brain stimulators are increasingly common therapies for patients with a large range of medical conditions, but a significant limitation of these devices is restricted compatibility with MRI," says Giorgio Bonmassar, PhD, of the Martinos Center, senior and corresponding article of the paper. "The tests performed on our prototype deep-brain stimulation lead indicate a three-fold reduction in heat generation, compared with a commercially available lead; and the use of such leads could significantly expand how many patients may safely access the benefits of MRI."

For many years the primary limitation to the use of MRI in patients with implanted devices was the risk that the powerful magnetic fields would dislodge devices containing ferromagnetic (attracted by magnetic fields) metals, but the devices now available avoid using those metals. However, the RF energy used in MRI can increase the electrical current induced in the nonmagnetic metallic wires at the center of presently available device leads, producing heat that can damage tissues at the site where a stimulating signal is delivered. Even though the FDA has authorized a group of "MR conditional" devices that can be used in some situations, those are limited to low-power scanners that cannot provide the information available from today's more powerful state-of-the-art MRI systems. It is estimated that around 300,000 patients worldwide are prevented from receiving MRI exams each year because of implanted devices.

The wires designed by the MGH/Martinos Center team use what is called resistive tapered stripline (RTS) technology that breaks up the RF-induced current increase by means of an abrupt change in the electrical conductivity of wires made from conductive polymers, a "cloaking" technique also used in some forms of stealth aircraft. After calculating the features required to produce an RTS lead that would minimize heat generation, the investigators designed and tested a deep-brain stimulation device with such a lead in a standard system used for MRI testing of medical implants - a gel model the size of an adult human head and torso. Compared with a commercially available lead, the RTS lead generated less than half the heat produced by exposure to a powerful MRI-RF field, a result well within current FDA limits.

Study co-author Emad Eskandar, MD, of the MGH Department of Neurosurgery notes that the ability to conduct MR exams on patients with deep-brain stimulation implants would significantly improve the critical process of ensuring that the signal is being delivered to the right area, something that is not possible with CT imaging. "For epilepsy patients and their providers, brain MRIs could provide much more accurate information about the sites where seizures originate and their relation to other brain structures, maximizing the effectiveness and improving the safety of implants that reduce or eliminate seizures. MR-compatible leads also would allow patients with brain implants to have MRIs of other parts of their body - knee, spine, breast - something that is currently prohibited," he says.

Bonmassar stresses that the team's RTS lead technology would be applicable to any type of active implant - including pacemakers, defibrillators and spinal cord stimulators. The research team is now pursuing an FDA Investigational Device Exemption that will allow clinical trials of devices with RTS leads. "The Obama administration's BRAIN initiative is sponsoring grant applications to study recording and/or stimulation devices to treat nervous system disorders and better understand the human brain," he says. "By pursuing these opportunities we hope that one day no patients will be denied access to state-of-the-art MRI examinations."

INFORMATION:

Bonmassar is an assistant professor of Radiology, and Eskandar is the Pappas Professor of Neurosciences at Harvard Medical School. The co-lead authors of the Scientific Reports paper are Peter Serano, University of Maryland, and Leonardo Angelone, PhD, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Husam Katnani, PhD, MGH Neurology, is also a co-author. The study was supported by National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant U01-NS075026, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering grant 1R21EB016449-01A1, National Center for Research Resources grant P41-RR14075, and by the MIND Institute. Massachusetts General Hospital has filed a patent application for the technology described in this paper.

Massachusetts General Hospital , founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The MGH conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, with an annual research budget of more than $760 million and major research centers in AIDS, cardiovascular research, cancer, computational and integrative biology, cutaneous biology, human genetics, medical imaging, neurodegenerative disorders, regenerative medicine, reproductive biology, systems biology, transplantation biology and photomedicine.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-05-05

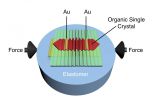

AMHERST, Mass. -- A revolution is coming in flexible electronic technologies as cheaper, more flexible, organic transistors come on the scene to replace expensive, rigid, silicone-based semiconductors, but not enough is known about how bending in these new thin-film electronic devices will affect their performance, say materials scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Writing in the current issue of Nature Communications, polymer scientists Alejandro Briseño and Alfred Crosby at UMass Amherst, with their doctoral student Marcos Reyes-Martinez, now ...

2015-05-05

ALEXANDRIA, VA, MAY 5, 2015 -- A statistical analysis of Job Corps data strongly suggests positive average effects on wages for individuals who participated in the federal job-training program.

Results of the analysis recently were included in an article in the Journal of Business & Economic Statistics (http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/ubes20/current), a professional journal published by the American Statistical Association . The study was conducted by Xuan Chen of Renmin University of China and Carlos A. Flores of California Polytechnic State University.

Job Corps is ...

2015-05-05

DURHAM, N.C. -- A 12-week dose of an investigational three-drug hepatitis C combination cleared the virus in 93 percent of patients with liver cirrhosis who hadn't previously been treated, according to a study in the May 5, 2015, issue of The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Bristol-Myers Squibb funded the trial of the combination of three drugs -- daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and beclabuvir. None of the three drugs are FDA-approved, but daclatasvir is currently under review by the FDA. Duke Medicine researchers collaborated on the design and analysis of the ...

2015-05-05

In two studies appearing in the May 5 issue of JAMA, patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1 infection and with or without cirrhosis achieved high rates of sustained virologic response after 12 weeks of treatment with a combination of the direct-acting-antiviral drugs daclatasvir, asunaprevir, and beclabuvir.

Current estimates indicate that 130 million to 150 million people worldwide are chronically infected with HCV, resulting in up to 350,000 deaths per year. Of the 7 HCV genotypes identified, genotype 1 is the most prevalent worldwide, accounting for ...

2015-05-05

Among patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) who recovered following standard treatment with the antibiotics metronidazole or vancomycin, oral administration of spores of a strain of C difficile that does not produce toxins colonized the gastrointestinal tract and significantly reduced CDI recurrence, according to a study in the May 5 issue of JAMA.

C difficile is the cause of one of the most common and deadly health care-associated infections, linked to 29,000 U.S. deaths each year. Rates of CDI remain at unprecedented high levels in U.S. hospitals. Clinical ...

2015-05-05

In what is a major step towards the prevention of recurring bouts of Clostridium difficile (Cdiff) infection, an international team led by Dale Gerding, MD, Hines Veterans Administration (VA) research physician and professor of Medicine at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, has shown that giving spores of non-toxic Cdiff by mouth is effective in stopping repeated bouts of Cdiff infection which occurs in 25-30 percent of patients who suffer an initial episode of diarrhea or colitis. The study is published in the May 5 issue of the Journal of American ...

2015-05-05

For the first time, scientists have imaged thunder, visually capturing the sound waves created by artificially triggered lightning. Researchers from Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) are presenting the first images at a joint meeting of American and Canadian geophysical societies in Montreal, Canada, May 3-7.

"Lightning strikes the Earth more than 4 million times a day, yet the physics behind this violent process remain poorly understood," said Dr. Maher A. Dayeh, a research scientist in the SwRI Space Science and Engineering Division. "While we understand the general ...

2015-05-05

Employing online training programs to teach psychotherapists how to use newer evidence-based treatments can be as successful as in-person instruction, according to a new RAND Corporation study.

Psychotherapy treatments can lag years behind what research has shown to be effective because there simply are not enough clinicians trained in new methods. That means that many people with mental health disorders are not getting the most effective nonpharmacological treatments, RAND researchers say.

For one such treatment, Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy to treat bipolar ...

2015-05-05

Tropical Storm Noul is still threatening Yap Island located in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, and a part of the Federated States of Micronesia. Micronesia has posted a typhoon warning for the tiny island. The storm is currently 22 miles south-southwest of Ulithi (one of the outer islands of the State of Yap) and is moving west at 2 knots per hour. Maximum sustained winds for the storm is 55 knots gusting to 70 knots and maximum wave height is 20 feet.

Noul is moving to the west and is expected to veer west northwest and later to the northwest. ...

2015-05-05

After gobbling the fourth Oreo in a row while bathed in refrigerator light, have you ever thought, "That wasn't enough," and then proceeded to search for something more?

Researchers at BYU have shed new light on why you, your friends, neighbors and most everyone you know tend to snack at night: some areas of the brain don't get the same "food high" in the evening.

In a newly published study, exercise sciences professors and a neuroscientist at BYU used MRI to measure how people's brains respond to high- and low-calorie food images at different times of the day. The ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Redesigned systems may increase access to MRI for patients with implanted medical devices

Massachusetts General-led team uses stealth technology to prevent excess heating of signal-carrying device leads