(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- Duke University scientists have discovered a previously unknown dual mechanism that slows peat decay and may help reduce carbon dioxide emissions from peatlands during times of drought.

"This discovery could hold the key to helping us find a way to significantly reduce the risk that increased drought and global warming will change Earth's peatlands from carbon sinks into carbon sources, as many scientists have feared," said Curtis J. Richardson, director of the Duke University Wetland Center and professor of resource ecology at Duke's Nicholas School of the Environment.

The naturally occurring mechanism was discovered in 5,000-year-old pocosin bogs in coastal North Carolina. Preliminary field experiments suggest it may occur in, or be exportable to, peatlands in other regions as well.

"When we took peat extracts from the southern peatlands and put them into Canadian peatlands, they slowed down decomposition there, too," said Richardson.

Peatlands are wetlands that cover only 3 percent of Earth's land but store one-third of the planet's total soil carbon. Left undisturbed, stored carbon can remain locked in their organic soil for millennia due to natural antimicrobial compounds called phenolics that prevent the waterlogged peat from decaying.

If the peat dries out, however, many scientists have theorized peatlands would switch from storing carbon to pumping it out instead.

"The accepted scientific paradigm is that prolonged drought, coupled with global warming and increased drainage of peatlands for agriculture and forestry, will lower water levels. This could cause peatlands to dry out, decay and release massive amounts of carbon back into the atmosphere," Richardson said. "Our research supports a less dire scenario. It finds that moderate long-term drought might have less impact on the release of carbon dioxide from peatlands than expected."

The reason, he said, lies buried in the peatland soil itself.

By comparing the chemistry of soil from pocosin bog peatlands in North Carolina with soil from boreal peatlands in Canada, Richardson and his team discovered a significant and previously unrecognized difference between the two.

"Southern wooded peatlands are up to 5,000 years old and have more complex plant-derived compounds that have allowed them to adapt to drought through a mechanism that regulates the buildup of phenolics and helps slow down decomposition," said Hongjun Wang, a research scientist at the Duke Wetland Center.

This natural adaptation, which was not found as abundantly in soil from boreal peatlands of the north, protects stored carbon directly by reducing decay-promoting phenol oxidase activity during short-term drought. The mechanism also indirectly protects stored carbon by spurring a shift in the peatlands' plant cover in response to moderate long-term drought. As water levels drop, plants that contain low levels of phenolics, such as sphagnum moss, ferns and sedges, are replaced by trees and shrubs, which are high in the decay-retarding compounds.

"This dual mechanism helps peat resist decay and adapt to climate change," Wang said.

He believes high-phenolic shrubs could naturally expand into northern peatlands or be introduced there as water levels drop, offering hope that scientists might be able to reduce the risk of large carbon releases.

"We still need to identify the specific aromatic components or groups of phenolics that are responsible for the decay-retarding mechanism," Richardson said. "Plants produce and contain thousands of compounds, so this may take time. But it will be worth the effort. What we learn will provide us with new approaches for managing storage and losses of carbon from millions of acres of peatlands worldwide."

INFORMATION:

Richardson and Wang, who also holds a research appointment at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, published their study in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Climate Change. Mengchi Ho, associate in research at the Duke Wetland Center, co-authored the study.

Principal funding came from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Additional funding came from The Nature Conservancy of North Carolina and the Duke University Wetland Center Endowment.

CITATION: "Dual-Controls on Carbon Loss During Drought in Peatlands," Hongjun Wang, Curtis J. Richardson, Mengchi Ho. Nature Climate Change, May 11, 2015. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2643.

Fifty miles out to sea from San Diego, in the middle of April, under a perfectly clear blue sky, NOAA Fisheries scientists Tomo Eguchi and Jeff Seminoff leaned over the side of a rubber inflatable boat and lowered a juvenile loggerhead sea turtle into the water. That turtle was a trailblazer -- the first of its kind ever released off the West Coast of the United States with a satellite transmitter attached.

Once he was in the water, the little guy -- "he's about the size of a dinner plate," Seminoff said -- paddled away to begin a long journey. He's been beaming back ...

Going to the dentist might have just gotten a little less scary for the estimated 1 in 68 U.S. children with autism spectrum disorder as well as children with dental anxiety, thanks to new research from USC.

In an article published on May 1 by the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, researchers from USC and Children's Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) examined the feasibility of adapting dental environments to be more calming for children with autism spectrum disorder.

"The regular dental environment can be quite frightening for children with autism who, not knowing ...

PITTSBURGH, May 11, 2015 - A computer simulation, or "in silico" model, of the body's inflammatory response to traumatic injury accurately replicated known individual outcomes and predicted population results counter to expectations, according to a study recently published in Science Translational Medicine by a University of Pittsburgh research team.

Traumatic injury is a major health care problem worldwide. Trauma induces acute inflammation in the body with the recruitment of many kinds of cells and molecular factors that are crucial for tissue survival, explained senior ...

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- Over nearly 15 years spent studying ticks, Indiana University's Keith Clay has found southern Indiana to be an oasis free from Lyme disease, the condition most associated with these arachnids that are the second most common parasitic disease vector on Earth.

He has also seen signs that this low-risk environment is changing, both in Indiana and in other regions of the U.S.

A Distinguished Professor in the IU Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Biology, Clay has received support for his research on ticks from over $2.7 million ...

Around 55 million years ago, an abrupt global warming event triggered a highly corrosive deep-water current through the North Atlantic Ocean. The current's origin puzzled scientists for a decade, but an international team of researchers has now discovered how it formed and the findings may have implications for the carbon dioxide emission sensitivity of today's climate.

The researchers explored the acidification of the ocean that occurred during a period known as the Paleocene Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), when the Earth warmed 9 degree Fahrenheit in response to a ...

On Sunday, May 10, 2015, Super Typhoon Noul (designated Dodong in the Philippines) made landfall in Santa Ana, a coastal town in Cagayan on the northeastern tip of the Philippine Islands. Close to 2,500 residents evacuated as the storm crossed over, and as of today no major damage or injuries have been reported. Trees were downed by the high winds and power outages occurred during the storm. Noul is expected to weaken now that it has made land, and to move faster as it rides strong surrounding winds. It is forecast to completely leave the Philippines by Tuesday morning ...

This was no Mother's Day gift to South Carolina as Ana made landfall on Sunday. Just before 6 am, Ana made landfall north of Myrtle Beach, SC with sustained winds of 45 mph, lower than the 50 mph winds it was packing as a tropical storm over the Atlantic. After making landfall, Ana transitioned to a tropical depression and is currently moving northward through North Carolina and will continue its trek northward. Heavy rain and storm surges are expected in the storm's wake. Storms of this size will create dangerous rip currents so beachgoers should be wary of Ana as ...

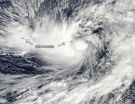

The MODIS instrument on the Aqua satellite captured this image of Tropical Storm Dolphin riding roughshod over the Federated States of Micronesia. Dolphin strengthened to tropical storm status between Bulletin 272 and 273 (1620 GMT and 2200 GMT) of the Joint Typhoon Weather Center on May 09, 2015.

The AIRS instrument on Aqua captured the images below of Dolphin between 10:59 pm EDT on May 9 and 11:00 am May 10 (02:59 UTC/15:17 UTC).

Dolphin is currently located (as of 5:00am EDT/0900 GMT) 464 miles ENE of Chuuk moving northwest at 9 knots (10 mph). It is expected ...

New York, NY - The United States has a serious shortage of organs for transplants, resulting in unnecessary deaths every day. However, a fairly simple and ethical change in policy would greatly expand the nation's organ pool while respecting autonomy, choice, and vulnerability of a deceased's family or authorized caregiver, according to medical ethicists and an emergency physician at NYU Langone Medical Center.

The authors share their views in a new article in the May 11 online edition of the Journal of American Medical Association's "Viewpoint" section.

"The U.S. ...

Hepatitis B stimulates processes that deprive the body's immune cells of key nutrients that they need to function, finds new UCL-led research funded by the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust.

The work helps to explain why the immune system cannot control hepatitis B virus infection once it becomes established in the liver, and offers a target for potential curative treatments down the line. The research also offers insights into controlling the immune system, which could be useful for organ transplantation and treating auto-immune diseases.

Worldwide 240 million ...