(Press-News.org) New research published in Nature Communications led by Meiyun Lin of NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and NOAA's cooperative institute at Princeton University, reveals a strong connection between high ozone days in the western U.S. during late spring and La Niña, an ocean-atmosphere phenomena that affects global weather patterns.

Recognizing this link offers an opportunity to forecast ozone several months in advance, which could improve public education to reduce health effects. It would also help western U.S. air quality managers prepare to track these events, which can have implications for attaining the national ozone standard.

Exposure to ozone is harmful to human health, can cause breathing difficulty, coughing, scratchy and sore throats, and asthma attacks, and can damage sensitive plants.

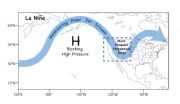

"Ozone in the stratosphere, located 6 to 30 miles (10 to 48 kilometers) above the ground, typically stays in the stratosphere," said Lin. "But not on some days in late spring following a strong La Niña winter. That's when the polar jet stream meanders southward over the western U.S. and facilitates intrusions of stratospheric ozone to ground level where people live."

Over the last two decades, there have been three La Niña events - 1998-1999, 2007-2008 and 2010-2011. After these events, scientists saw spikes in ground level ozone for periods of two to three days at a time during late spring in high altitude locations of the U.S. West.

While high ozone typically occurs on muggy summer days when pollution from cars and power plants fuels the formation of regional ozone pollution, high-altitude regions of the U.S. West sometimes have a different source of high ozone levels in late spring. On these days, strong gusts of cold dry air associated with downward transport of ozone from the stratosphere pose a risk to these communities.

Lin and her colleagues found that these deep intrusions of stratospheric ozone could add 20 to 40 parts per billion of ozone to the ground-level ozone concentration, which can provide over half the ozone needed to exceed the standard set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA has proposed tightening that standard currently set at 75 parts per billion for an eight-hour average to between 65 and 70 parts per billion.

Under the Clean Air Act, these deep stratospheric ozone intrusions can be classified as "exceptional events" that are not counted towards EPA attainment determinations. As our national ozone standard becomes more stringent, the relative importance of these stratospheric intrusions grows, leaving less room for human-caused emissions to contribute to ozone pollution prior to exceeding the level set by the U.S. EPA.

"Regardless of whether these events count towards non-attainment, people are living in these regions and the possibility of predicting a high-ozone season might allow for public education to minimize adverse health effects," said Arlene Fiore, an atmospheric scientist at Columbia University and a co-author of the research.

Predicting where and when stratospheric ozone intrusions may occur would also provide time to deploy air sensors to obtain evidence as to how much of ground-level ozone can be attributed to these naturally occurring intrusions and how much is due to human-caused emissions.

The study involved collaboration across two NOAA laboratories, NOAA's cooperative institutes at Princeton and the University of Colorado Boulder, and scientists at partner institutions in the U.S., Canada and Austria. It was also supported in part by the NASA Air Quality Applied Sciences Team whose mission is to apply earth science data to help address air quality management needs.

"This study brings together observations and chemistry-climate modeling to help understand the processes that contribute to springtime high-ozone events in the western U.S.," said Andrew Langford, an atmospheric scientist at NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, whose teams measure ozone concentrations using lidar and balloon-borne sensors.

"You've heard about good ozone, the kind found high in the stratosphere that protects the earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation," said Langford. "And you've heard about bad ozone at ground level. This study looks at the factors that cause good ozone to go bad."

INFORMATION:

Lin, Fiore and Langford conducted the research with Larry Horowitz of NOAA's Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory; Samuel Oltmans of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, who works in NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory; David Tarasick of Environment Canada; and Harald Rieder of the University of Graz in Austria.

LAWRENCE -- Political discussions conducted on social networking sites like Facebook mirror traditional offline discussions and don't provide a window into previously untapped participants in the political process, according to a new study that includes two University of Kansas researchers.

"Social networking is important, but what we've shown in political science is that the people who are using the Internet, be it Facebook, Twitter or whatever else for political activities, are really the same people who are politically active offline anyway," said Patrick Miller, a ...

AURORA, Colo. (May 12, 2015) - A team of neuroscientists and bioengineers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have created a miniature, fiber-optic microscope designed to peer deeply inside a living brain.

The researchers, including scientists from the University of Colorado Boulder, published details of their revolutionary microscope in the latest issue of Optics Letters journal.

"Microscopes today penetrate only about one millimeter into the brain but almost everything we want to see is deeper than that," said Prof. Diego Restrepo, PhD, one of the ...

A study of 2,377 children with autism, their parents and siblings has revealed novel insights into the genetics of the condition.

The findings were reported May 11 in Nature Genetics.

By analyzing data from families with one child with autism and one or more children without the condition, the researchers collected new information on how different types of mutations affect autism risk. The genetic data was obtained from exome sequencing, which looks at only the protein-coding portions of the genome.

Significant progress in the past five years has been made in ...

The fixed-dose combination aclidinium bromide/formoterol has been approved since November 2014 for long-term treatment of adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) examined in a dossier assessment whether this drug combination offers an added benefit over the appropriate comparator therapy.

According to the findings, there is an indication of minor added benefit for adult patients with moderate COPD (grade II). For adults with grade III and fewer than 2 exacerbations (flare-ups) per ...

Male HIV patients in rural South Africa reach the low immunity levels required to become eligible for antiretroviral treatment in less than half the time it takes for immunity levels to drop to similar levels in women, according to new research from the University of Southampton.

Researchers also found a link between potential proxy measures of nutritional status and disease progression, with those reporting food shortages and use of nutritional supplements reaching lower levels of immunity faster.

CD4 cell count is a measure of the immune system which indicates the ...

They are 'strange' materials, insulators on the inside and conductors on the surface. They also have properties that make them excellent candidates for the development of spintronics ('spin-based electronics') and more in general quantum computing. However, they are also elusive as their properties are extremely difficult to observe. Now a SISSA study, published in Physical Review Letters, proposes a new family of materials whose topological state can be directly observed experimentally, thus simplifying things for researchers.

"What interests us of topological insulators ...

A gap year between high school and the start of university studies does not weaken young people's enthusiasm to study or their overall performance once the studies have commenced. On the other hand, adolescents who continue to university studies directly after upper secondary school are more resilient in their studies and more committed to the study goals. However, young people who transfer directly to university are more stressed than those who start their studies after a gap year. These research results have been achieved in the Academy of Finland's research programme ...

In a study published this month in Malaria Journal, researchers from Uppsala University and other institutions present a new model for systematically evaluating new malaria treatment programs in routine conditions across multiple countries.

Despite major investments in malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) in recent years, there remains limited evidence of their impact on treatment decisions in routine program conditions. Evidence to date is largely derived from small-scale facility studies conducted within a limited number of countries, notably Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, ...

It is six times more expensive for society - and for you individually - if you travel by car instead of cycling. This has been shown in a Lund University study of Copenhagen, a city of cyclists. It is the first time a price has been put on car use as compared to cycling.

In the comparative study, Stefan Gössling from Lund University and Andy S. Choi from the University of Queensland have investigated a cost-benefit analysis that the Copenhagen Municipality uses to determine whether new cycling infrastructure should be built.

It considers how much cars cost society ...

Offenders enrolled in alcohol treatment programmes as part of their sentence are significantly less likely to be charged or reconvicted in the 12 months following their programme, a study led by Plymouth University has shown.

Researchers from the University's School of Psychology led a project, supported by the European Social Fund, which saw males with alcohol problems related to offending being assigned to a range of different treatments when convicted.

They then calculated the participants' charged and reconviction rates over the following year, with the results ...