(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - A new study in animals suggests that skipping meals sets off a series of metabolic miscues that can result in abdominal weight gain.

In the study, mice that ate all of their food as a single meal and fasted the rest of the day developed insulin resistance in their livers - which scientists consider a telltale sign of prediabetes. When the liver doesn't respond to insulin signals telling it to stop producing glucose, that extra sugar in the blood is stored as fat.

These mice initially were put on a restricted diet and lost weight compared to controls that had unlimited access to food. The restricted-diet mice regained weight as calories were added back into their diets and nearly caught up to controls by the study's end.

But fat around their middles - the equivalent to human belly fat - weighed more in the restricted-diet mice than in mice that were free to nibble all day long. An excess of that kind of fat is associated with insulin resistance and risk for type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

"This does support the notion that small meals throughout the day can be helpful for weight loss, though that may not be practical for many people," said Martha Belury, professor of human nutrition at The Ohio State University and senior author of the study. "But you definitely don't want to skip meals to save calories because it sets your body up for larger fluctuations in insulin and glucose and could be setting you up for more fat gain instead of fat loss."

The research is published online in the Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry.

Belury and colleagues were able to tie these findings to the human tendency to skip meals because of the behavior they expected to see - based on previous work - in the mice on restricted diets. For three days, these mice received half of the calories that were consumed daily by control mice. Food was gradually added so that by day six, all mice received the same amount of food each day.

But the mice that had been on restricted diets developed gorging behavior that persisted throughout the study, meaning they finished their day's worth of food in about four hours and then ended up fasting for the next 20 hours.

"With the mice, this is basically bingeing and then fasting," Belury said. "People don't necessarily do that over a 24-hour period, but some people do eat just one large meal a day."

The gorging and fasting in these mice affected a host of metabolic measures that the researchers attributed to a spike and then severe drop in insulin production. In mice that gorged and then fasted, the researchers saw elevations in inflammation, higher activation of genes that promote storage of fatty molecules and plumper fat cells - especially in the abdominal area - compared to the mice that nibbled all day.

To check for insulin resistance, the scientists used a sophisticated technique to assess glucose production. The liver pumps out glucose when it receives signals that insulin levels are low - for example, while people sleep, the liver supplies glucose to the brain. But that production stops after a meal, when insulin is released by the pancreas and performs its main task of removing sugar from the blood and shepherding the glucose to multiple types of cells that absorb it for energy.

With this research technique, Belury and colleagues found that glucose lingered in the blood of mice that gorged and fasted - meaning the liver wasn't getting the insulin message.

"Under conditions when the liver is not stimulated by insulin, increased glucose output from the liver means the liver isn't responding to signals telling it to shut down glucose production," Belury said. "These mice don't have type 2 diabetes yet, but they're not responding to insulin anymore and that state of insulin resistance is referred to as prediabetes."

Insulin resistance is also a risk for gaining abdominal fat known as white adipose tissue, which stores energy.

"Even though the gorging and fasting mice had about the same body weights as control mice, their adipose depots were heavier. If you're pumping out more sugar into the blood, adipose is happy to pick up glucose and store it. That makes for a happy fat cell - but it's not the one you want to have. We want to shrink these cells to reduce fat tissue," Belury said.

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the Carol S. Kennedy endowment, the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, a Pelotonia graduate fellowship and grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Co-authors include Kara Kliewer, Jia-Yu Ke, Hui-Young Lee, Michael Stout and Rachel Cole of the Department of Human Sciences at Ohio State; and Varman Samuel and Gerald Shulman of Yale University.

Contact: Martha Belury, 614-292-1680; Belury.1@osu.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, 614-292-8152; Caldwell.151@osu.edu

(SACRAMENTO, Calif.) -- Many of those who should get it, don't. And many of those who shouldn't, do. That's the story of a common screening test for osteoporosis, according to new research from UC Davis Health System.

The study, published online today in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, found that screening rates increased sharply among women at age 50, despite guidelines suggesting screening at age 65 unless risk factors are present. The presence of risk factors only had a modest influence on screening decisions.

Osteoporosis causes bone density to diminish ...

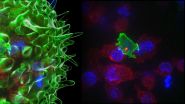

A dramatic video has captured the behaviour of cytotoxic T cells - the body's 'serial killers' - as they hunt down and eliminate cancer cells before moving on to their next target.

In a study published today in the journal Immunity, a collaboration of researchers from the UK and the USA, led by Professor Gillian Griffiths at the University of Cambridge, describe how specialised members of our white blood cells known as cytotoxic T cells destroy tumour cells and virally-infected cells. Using state-of-the-art imaging techniques, the research team, with funding from the ...

Decades' worth of textbook precepts about how our immune systems manage to avoid attacking our own tissues may be wrong.

Contradicting a long-held belief that self-reactive immune cells are weeded out early in life in an organ called the thymus, a new study by Stanford University School of Medicine scientists has revealed that vast numbers of these cells remain in circulation well into adulthood.

"This overturns 25 years of what we've been teaching," said Mark Davis, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology and director of Stanford's Institute for Immunity, Transplantation ...

Scientists are reporting development of a new way to modify interleukin-2 (IL-2), a substance known as a cytokine that plays key roles in regulating immune system responses, in order to fine-tune its actions. Harnessing the action of IL-2 in a controllable fashion is of clinical interest with potential benefit in a range of situations, including transplantation and autoimmune disease. The modified IL-2 molecules inhibited the actions of endogenous IL-2, potentially more effectively than existing agents, as well as inhibited the actions of another interleukin, IL-15, with ...

A team led by researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard has found that the most common bacterial community in the genital tract among healthy South Africa women not only is significantly different from that of women in developed countries but also leads to elevated levels of inflammatory proteins. In a paper in the May 19 issue of Immunity, the investigators describe finding potential mechanisms by which particular bacterial species induce inflammation and show that the presence of those species and of elevated ...

Ever since single-layer graphene burst onto the science scene in 2004, the possibilities for the promising material have seemed nearly endless. With its high electrical conductivity, ability to store energy, and ultra-strong and lightweight structure, graphene has potential for many applications in electronics, energy, the environment, and even medicine.

Now a team of Northwestern University researchers has found a way to print three-dimensional structures with graphene nanoflakes. The fast and efficient method could open up new opportunities for using graphene printed ...

HIV infections continue to rise in a new generation of young, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (YMSM) despite three decades of HIV prevention as well as recent availability of biomedical technologies to prevent infection. In the U.S., it is estimated that 63% of incident HIV infections in 2010 were among YMSM despite the fact that they represent a very small portion of the population. Given this heightened risk for HIV seroconversion among YMSM, researchers at New York University's Center for Health, Identity, Behavior & Prevention Studies (CHIBPS) sought ...

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- Why do some cancer cells break away from a tumor and travel to distant parts of the body? A team of oncologists and engineers from the University of Michigan teamed up to help understand this crucial question.

Cancer becomes deadly when it spreads, or metastasizes. Not all cells have the same ability to travel through the body, but researchers don't understand why.

In a paper published in Scientific Reports, researchers describe a new device that is able to sort cells based on their ability to move. The researchers were then able to take the sorted ...

Run far or run fast? That is one of the questions NASA is trying to answer with one of its latest studies--and the answers may help keep us in shape on Earth, as well as in space. Even with regular exercise, astronauts who spend an extended period of time in space experience muscle weakening, bone loss, and decreased cardiovascular conditioning. This is because they no longer have to work against gravity in everyday living.

NASA's Human Research Program Integrated Resistance and Aerobic Training study, known as iRAT, completed recently to evaluate the use of high intensity ...

Human error is estimated to cause more than 90% of traffic accidents, a percentage that might be drastically reduced by the implementation of self-driving cars featuring smart systems that control most aspects of driving. Although the potential benefits of self-driving cars have been widely touted, their success on the roadways of the near future is largely reliant on whether or not drivers are willing to trust these smart systems enough to hand over the wheel. A new study published in Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society evaluated whether ...