(Press-News.org) For more than a decade, scientists have had a working map of the human genome, a complete picture of the DNA sequence that encodes human life. But new pages are still being added to that atlas: maps of chemical markers called methyl groups that stud strands of DNA and influence which genes are repressed and when.

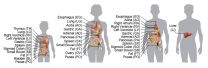

Now, Salk scientists have constructed the most comprehensive maps yet of these chemical patterns--collectively called the epigenome--in more than a dozen different human organs from individual donors (including a woman, man and child). While the methylation does not change an individual's inherited genetic sequence, research has increasingly shown it has a profound effect on development and health.

"What we found is that not all organs we surveyed are equal in terms of their methylation patterns," says senior author Joseph R. Ecker, professor and director of Salk's Genomic Analysis Laboratory and codirector of The Center of Excellence for Stem Cell Genomics. "The signatures of methylation are distinct enough between organs that we can look at the methylation patterns of a tissue and know whether the tissue is muscle or thymus or pancreas." The new data was published June 1, 2015 in Nature.

While the genome of an individual is the same in every cell, epigenomes vary since they are closely related to the genes a cell is actually using at any given time. Methylation marks help blood cells ignore the genes required to be a brain or liver cell, for instance. And they can vary over time--a change in a person's age, diet or environment, for instance, has been shown to affect methylation.

"We wanted to make a baseline assessment of what the epigenome, in particular DNA methylation, looks like in normal human organs," says Ecker. To do that, the scientists collected cells from 18 organs in 4 individuals and mapped out their methylation profiles.

As expected, the patterns aligned somewhat with genes known to be important for a cell's function--there was less methylation close to muscle genes in cells collected from muscle, for instance. But other aspects of the new maps were surprising. The researchers detected an unusual form of methylation, called non-CG methylation, which was thought to be widespread only in the brain and stem cells.

"The only place this had been observed before was in the brain, skeletal muscle, germ cells and stem cells," says Matthew Schultz, formerly a graduate student in the Ecker lab and a first author of the new work. "So, to see it in a variety of normal adult tissues was really exciting." Researchers don't yet know the function of that non-CG methylation in adults, but hypothesize that it may suggest the presence of stem cell populations in the adult tissues.

The team found other surprises in their research, which point to new avenues to explore. For example, they found that many regions showing dynamic methylation aren't located where expected--in a section of DNA called the promoter, as well as the regulatory regions that are upstream of the promoter. "In the past, people have really thought the promoter or the upstream regions are where everything is happening," says Ecker. "But we found that methylation changes that are most correlated with gene transcription are often in the downstream regions of the promoter." The observation could affect how and where researchers search for methylation when they're studying how an individual gene is regulated.

Another surprise was how extensively organs differed from each other in the degree of genome-wide methylation. The pancreas had an unusually low level of methylation, while the thymus had high levels of methylation. Researchers don't yet know why.

The new results just scratch the surface of completely understanding DNA methylation patterns--there are dozens more organs to profile, numerous unknowns about what shapes and changes the epigenome, and questions about whether different cells--even within a single organ--vary in their methylation patterns.

"What would be interesting to do next is split out different cell types," says Yupeng He, a graduate student in the Ecker lab and co-first author of the new paper. "The samples we have are heterogeneous mixtures of many cells."

The researchers hope the results offer a jumping off point, however, to start understanding how diseases, such as those affecting the organs they profiled, may be reflected in changes to the epigenome.

"You could imagine that eventually, if someone is having a problem, a biopsy might not only look at characterizing the cells or genes, but the epigenome as well," says Ecker.

INFORMATION:

Other researchers on the study were Manoj Hariharan, Eran A. Mukamel, Joseph R. Nery, Mark A. Urich, Huaming Chen, and Terrence J. Sejnowski, of the Salk Institute; John W. Whitaker, Siddarth Selvaraj and Wei Wang, of the University of California, San Diego; Danny Leung, Nisha Rajagopal, Inkyung Jung, Anthony D. Schmitt and Bing Ren, of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research; Shin Lin, of Stanford University; and Yiing Lin, of the Washington University School of Medicine.

The work and the researchers involved were supported by the National Institutes of Health Epigenome Roadmap Project, the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines. Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, M.D., the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- New compounds that specifically attack fungal infections without attacking human cells could transform treatment for such infections and point the way to targeted medicines that evade antibiotic resistance.

Led by University of Illinois chemistry professor Martin D. Burke, a team of chemists, microbiologists and immunologists developed and tested several derivatives of the antifungal drug amphotericin B (pronounced am-foe-TARE-uh-sin B). They published their findings in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Amphotericin B is doctors' last, best defense ...

WASHINGTON, DC, June 1, 2015 -- Non-heterosexual women who feel a disconnect between who they are attracted to and how they identify themselves may have a higher risk of alcohol abuse, according to a new study led by Amelia E. Talley, an assistant professor in Texas Tech University's Department of Psychological Sciences.

The study, titled "Longitudinal Associations among Discordant Sexual Orientation Dimensions and Hazardous Drinking in a Cohort of Sexual Minority Women," appears in the June issue of the Journal of Health and Social Behavior. It delves into the reasons ...

A new study links a commonly used household pesticide with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and young teens.

The study found an association between pyrethroid pesticide exposure and ADHD, particularly in terms of hyperactivity and impulsivity, rather than inattentiveness. The association was stronger in boys than in girls.

The study, led by researchers at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, is published online in the journal Environmental Health.

"Given the growing use of pyrethroid pesticides and the perception that they may ...

WASHINGTON, D.C. - In northwestern Greenland, glaciers flow from the main ice sheet to the ocean in see-sawing seasonal patterns. The ice generally flows faster in the summer than in winter, and the ends of glaciers, jutting out into the ocean, also advance and retreat with the seasons.

Now, a new analysis shows some important connections between these seasonal patterns, sea ice cover and longer-term trends. Glaciologists hope the findings, accepted for publication in the June issue of the American Geophysical Union's Journal of Geophysical Research-Earth Surface and ...

Washington, DC, June 1, 2015 - Tweets regarding the Ebola outbreak in West Africa last summer reached more than 60 million people in the three days prior to official outbreak announcements, according to a study published in the June issue of the American Journal of Infection Control, the official publication of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

Researchers from the Columbia University School of Nursing in New York analyzed over 42,000 Ebola-related tweets posted to the social networking site Twitter, from July 24 - August ...

In the last 40 years, fructose, a simple carbohydrate derived from fruit and vegetables, has been on the increase in American diets. Because of the addition of high-fructose corn syrup to many soft drinks and processed baked goods, fructose currently accounts for 10 percent of caloric intake for U.S. citizens. Male adolescents are the top fructose consumers, deriving between 15 to 23 percent of their calories from fructose--three to four times more than the maximum levels recommended by the American Heart Association.

A recent study at the Beckman Institute for Advanced ...

Biology isn't the only reason women eat less as they near ovulation, a time when they are at their peak fertility.

Three new independent studies found that another part of the equation is a woman's desire to maintain her body's attractiveness, says social psychologist and assistant professor Andrea L. Meltzer, Southern Methodist University, Dallas.

Women nearing ovulation who also reported an increase in their motivation to manage their body attractiveness reported eating fewer calories out of a desire to lose weight, said Meltzer, lead researcher on the study.

When ...

Bethesda, MD (June 1, 2015) -- The antiviral drug telbivudine prevents perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV), according to a study1 in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association.

"If we are to decrease the global burden of hepatitis B, we need to start by addressing mother-to-infant transmission, which is the primary pathway of HBV infection," said study author Yuming Wang from Institute for Infectious Diseases, Southwest Hospital, Chongqing, China. "We ...

The following research will be presented at the American Physical Society's 2015 Division of Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics (DAMOP) meeting that will take place June 8-12, 2015 at the Hyatt Regency Columbus and the Greater Columbus Convention Center in Columbus, Ohio.

FINDING VENUS AND SEARCHING FOR EXOPLANETS

Thursday, June 11, 8:48 AM, Room: Franklin CD

Telescopes aren't the only way to detect the presence of Venus passing by. It's also now possible to measure the relative motion of the Earth and Sun so precisely that physicists can use the measurement to ...

Policy makers need to budget more than 288 million pounds over the next 40 years to adequately provide health care to all British soldiers who suffered amputations because of the Afghan war. This is the prediction of Major DS Edwards of the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine in the UK, in a new article appearing in the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, published by Springer. He led a study into the scale and long-term economic cost of military amputees following Britain's involvement in Afghanistan between 2003 and 2014.

The authors describe the traumatic ...