(Press-News.org) Today's computer chips pack billions of tiny transistors onto a plate of silicon within the width of a fingernail. Each transistor, just tens of nanometers wide, acts as a switch that, in concert with others, carries out a computer's computations. As dense forests of transistors signal back and forth, they give off heat -- which can fry the electronics, if a chip gets too hot.

Manufacturers commonly apply a classical diffusion theory to gauge a transistor's temperature rise in a computer chip. But now an experiment by MIT engineers suggests that this common theory doesn't hold up at extremely small length scales. The group's results indicate that the diffusion theory underestimates the temperature rise of nanoscale heat sources, such as a computer chip's transistors. Such a miscalculation could affect the reliability and performance of chips and other microelectronic devices.

"We verified that when the heat source is very small, you cannot use the diffusion theory to calculate temperature rise of a device. Temperature rise is higher than diffusion prediction, and in microelectronics, you don't want that to happen," says Professor Gang Chen, head of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at MIT. "So this might change the way people think about how to model thermal problems in microelectronics."

The group, including graduate student Lingping Zeng and Institute Professor Mildred Dresselhaus of MIT, Yongjie Hu of the University of California at Los Angeles, and Austin Minnich of Caltech, has published its results this week in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Phonon mean free path distribution

Chen and his colleagues came to their conclusion after devising an experiment to measure heat carriers' "mean free path" distribution in a material. In semiconductors and dielectrics, heat typically flows in the form of phonons -- wavelike particles that carry heat through a material and experience various scatterings during their propagation. A phonon's mean free path is the distance a phonon can carry heat before colliding with another particle; the longer a phonon's mean free path, the better it is able to carry, or conduct, heat.

As the mean free path can vary from phonon to phonon in a given material -- from several nanometers to microns -- the material exhibits a mean free path distribution, or range. Chen, the Carl Richard Soderberg Professor in Power Engineering at MIT, reasoned that measuring this distribution would provide a more detailed picture of a material's heat-carrying capability, enabling researchers to engineer materials, for example, using nanostructures to limit the distance that phonons travel.

The group sought to establish a framework and tool to measure the mean free path distribution in a number of technologically interesting materials. There are two thermal transport regimes: diffusive regime and quasiballistic regime. The former returns the bulk thermal conductivity, which masks the important mean free path distribution. To study phonons' mean free paths, the researchers realized they would need a small heat source compared with the phonon mean free path to access the quasiballistic regime, as larger heat sources would essentially mask individual phonons' effects.

Creating nanoscale heat sources was a significant challenge: Lasers can only be focused to a spot the size of the light's wavelength, about one micron -- more than 10 times the length of the mean free path in some phonons. To concentrate the energy of laser light to an even finer area, the team patterned aluminum dots of various sizes, from tens of micrometers down to 30 nanometers, across the surface of silicon, silicon germanium alloy, gallium arsenide, gallium nitride, and sapphire. Each dot absorbs and concentrates a laser's heat, which then flows through the underlying material as phonons.

In their experiments, Chen and his colleagues used microfabrication to vary the size of the aluminum dots, and measured the decay of a pulsed laser reflected from the material -- an indirect measure of the heat propagation in the material. They found that as the size of the heat source becomes smaller, the temperature rise deviates from the diffusion theory.

They interpret that as the metal dots, which are heat sources, become smaller, phonons leaving the dots tend to become "ballistic," shooting across the underlying material without scattering. In these cases, such phonons do not contribute much to a material's thermal conductivity. But for much larger heat sources acting on the same material, phonons tend to collide with other phonons and scatter more often. In these cases, the diffusion theory that is currently in use becomes valid.

A detailed transport picture

For each material, the researchers plotted a distribution of mean free paths, reconstructed from the heater-size-dependent thermal conductivity of a material. Overall, they observed the anticipated new picture of heat conduction: While the common, classical diffusion theory is applicable to large heat sources, it fails for small heat sources. By varying the size of heat sources, Chen and his colleagues can map out how far phonons travel between collisions, and how much they contribute to heat conduction.

Zeng says that the group's experimental setup can be used to better understand, and potentially tune, a material's thermal conductivity. For example, if an engineer desires a material with certain thermal properties, the mean free path distribution could serve as a blueprint to design specific "scattering centers" within the material -- locations that prompt phonon collisions, in turn scattering heat propagation, leading to reduced heat carrying ability. Although such effects are not desirable in keeping a computer chip cool, they are suitable in thermoelectric devices, which convert heat to electricity. For such applications, materials that are electrically conducting but thermally insulating are desired.

"The important thing is, we have a spectroscopy tool to measure the mean free path distribution, and that distribution is important for many technological applications," Zeng says.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded in part by in part by MIT's Solid-State Solar Thermal Energy Conversion Center, which is funded by U.S. Department of Energy.

Related links

ARCHIVE:

Tunneling across a tiny gap

ARCHIVE:

Refrigerator magnets

Bacteria and viruses have an obvious role in causing infectious diseases, but microbes have also been identified as the surprising cause of other illnesses, including cervical cancer (Human papilloma virus) and stomach ulcers (H. pylori bacteria).

A new study by University of Iowa microbiologists now suggests that bacteria may even be a cause of one of the most prevalent diseases of our time - Type 2 diabetes.

The research team led by Patrick Schlievert, PhD, professor and DEO of microbiology at the UI Carver College of Medicine, found that prolonged exposure to a toxin ...

As the world's population of older adults increases, so do conversations around successful aging -- including seniors' physical, mental and social well-being.

A variety of factors can impact aging adults' quality of life. Two big ones, according to new research from the University of Arizona, are the health and cognitive functioning of a person's spouse.

Analyzing data from more than 8,000 married couples -- with an average age in the early 60s -- researchers found that the physical health and cognitive functioning of a person's spouse can significantly affect a person's ...

A team of scientists at Virginia Commonwealth University has synthesized a powerful new magnetic material that could reduce the dependence of the United States and other nations on rare earth elements produced by China.

"The discovery opens the pathway to systematically improving the new material to outperform the current permanent magnets," said Shiv Khanna, Ph.D., a commonwealth professor in the Department of Physics in the College of Humanities and Sciences.

The new material consists of nanoparticles containing iron, cobalt and carbon atoms with a magnetic domain ...

COLLEGE PARK, Md. -- The introduction of Craigslist led to an increase in HIV-infection cases of 13.5 percent in Florida over a four-year period, according to a new study conducted at the University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business. The estimated medical costs for those patients will amount to $710 million over the course of their lives.

Online hookup sites have made it easier for people to have casual sex -- and also easier to transmit sexually transmitted diseases. The new study measured the magnitude of the effect of one platform on HIV infection rates ...

Selling one's body to provide another person with sexual pleasure and selling organs to restore another person's health are generally prohibited in North America on moral grounds, but two new University of Toronto Mississauga studies illustrate how additional information about the societal benefits of such transactions can have an impact on public approval.

The research, conducted by Professor Nicola Lacetera of the University of Toronto (Institute for Management and Innovation, U of T Mississauga, with a cross-appointment to the Rotman School of Management) and his ...

Going into space might wreak havoc on our bodies, but a new set of microgravity experiments may help shed light on new approaches for treating cartilage diseases on Earth. In a new research report published in the June 2015 issue of The FASEB Journal, a team of European scientists suggests that our cartilage--tissue that serves as a cushion between bones--might be able to survive microgravity relatively unscathed. Specifically, when in a microgravity environment, chondrocytes (a main component of cartilage) were more stable and showed only moderate alterations in shape ...

There's an urgent demand for new antimicrobial compounds that are effective against constantly emerging drug-resistant bacteria. Two robotic chemical-synthesizing machines, named Symphony X and Overture, have joined the search. Their specialty is creating custom nanoscale structures that mimic nature's proven designs. They're also fast, able to assemble dozens of compounds at a time.

The machines are located in a laboratory on the fifth floor of the Molecular Foundry, a DOE Office of Science User Facility at Berkeley Lab. They make peptoids, which are synthetic versions ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. -- If a picture is worth a thousand words, UF Health Type 1 diabetes researchers and their colleagues have tapped into an encyclopedia, revealing new insights into how young people cope with the disease.

The sophisticated scientific instrument? A camera.

More than 13,000 children and teens are diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes each year. To find out more about their experiences as they live with this chronic disorder, a group of diabetes researchers from three universities, including the University of Florida, gave 40 adolescents disposable cameras and ...

People with achromatopsia, an inherited eye disorder, see the world literally in black and white. Worse yet, their extreme sensitivity to light makes them nearly blind in bright sunlight. Now, researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and Shiley Eye Institute at UC San Diego Health System have identified a previously unknown gene mutation that underlies this disorder.

The study published online June 1 in the journal Nature Genetics.

"There are whole families with this sort of vision problem all over the world," said Jonathan Lin, MD, ...

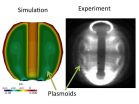

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy's Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) have for the first time simulated the formation of structures called "plasmoids" during Coaxial Helicity Injection (CHI), a process that could simplify the design of fusion facilities known as tokamaks. The findings, reported in the journal Physical Review Letters, involve the formation of plasmoids in the hot, charged plasma gas that fuels fusion reactions. These round structures carry current that could eliminate the need for solenoids - large magnetic coils that wind down the center ...