Now, new evidence published in the European Heart Journal [1] today (Wednesday) has shown that doctors who try to detect these heartbeat irregularities (known as arrhythmias) by focusing on the left ventricle of the heart, or on the right ventricle while an athlete is resting, will miss important signs of right ventricular dysfunction that can only be detected during exercise and that could be fatal.

The findings have important clinical implications because, at present, routine assessments of athletes with suspected arrhythmias often involve looking at the heart while it is resting, with a focus on the left ventricle.

Previous research by Professors Hein Heibuchel and André La Gerche had already demonstrated that the thin-walled right ventricle of the heart, which pumps blood through the lungs, is subjected to much greater stresses during exertion than the left ventricle, and that prolonged exercise is associated with temporary damage to the right ventricle.

In this new study, Prof La Gerche and his colleagues in Australia and Belgium have found that problems in the way the right ventricle works become apparent only during exercise and cannot be detected when an athlete is resting.

Prof La Gerche said: "You do not test a racing car while it is sitting in the garage. Similarly, you can't assess an athlete's heart until you assess it under the stress of exercise."

The researchers tested the performance of the hearts in 17 athletes with right ventricular arrhythmias, eight of whom had an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) in place to control the rhythm of their hearts, 10 healthy endurance athletes and seven non-athletes. They used several different imaging techniques to see the heart at rest and during exercise. Some of these techniques were invasive, such as cardiac magnetic resonance combined with catheters inserted in blood vessels to measure pressures, and some that were not, such as echocardiography, which uses ultrasound.

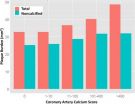

They found that measurements of how well the heart was functioning when the athletes were resting were similar in all three groups, as was left ventricular function during exercise. However, measurements taken while the participants were exercising showed changes in the functioning of the right ventricle in the athletes who were known to have arrhythmias when compared with the other two groups.

"By measuring the blood pressure in the lungs and the body during exercise we have shown that the right side of the heart has to increase its work more than the left side of the heart. Hence, the right side of the heart is a potential 'weak link' in athletes. In the normal healthy athletes, the right side of the heart was able to manage the increased work requirements. In the athletes with arrhythmias the right side of the heart was weak during exercise, it could not handle the increase in work and we could detect problems accurately that were not apparent at rest," explained Prof La Gerche, associate professor and head of sports cardiology at Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute, Melbourne, Australia, and visiting professor at University Hospitals Leuven, Belgium.

"The dysfunction of the right ventricle during exercise suggests that there is damage to the heart muscle. This damage is causing both weakness and heart rhythm problems. Whilst the weakness is mild, the heart rhythm problems are potentially life threatening."

Prof La Gerche found that there were few differences between the different imaging methods in their ability to detect right ventricular dysfunction. Non-invasive echocardiography could detect the changes accurately. In their paper, the authors write: "Given the widespread availability and cost-effectiveness of echocardiography, this is an important finding. While a focus on RV [right ventricle] measures is not commonly practiced, the measures employed in this study are relatively simple and could easily be included in clinical routine."

Prof La Gerche said: "Exercise echocardiography can be used right now to assess heart function in the manner that we have done. The only issue is that we cannot get good pictures with echocardiography in everyone, whereas it is always possible to get good images with magnetic resonance imaging. As cardiac magnetic resonance imaging becomes more and more mainstream, we think that this will become the test of choice."

Now the researchers are using the same techniques, but without invasive catheters, to assess more athletes. "It will be important to validate this study in a larger group of athletes and in athletes who are presenting for the first time in whom it is not yet clear whether or not their problem is serious," said Prof La Gerche. However, he thinks his findings could influence clinical practice now. "These results should stimulate cardiologists who manage athletes to pay greater attention to the right side of the heart. The tests that we describe are ready for clinical use right now and are not too challenging. It is simply a case of 'you will not find unless you look'."

In an accompanying editorial [2], Professor Sanjay Sharma, of St George's University of London (UK), who is medical director of the London Marathon and chair of the European Society of Cardiology's sports cardiology nucleus, and Dr Abbas Zaidi, a research fellow at St George's University of London, and a marathon runner, describe the study as "novel and important in several regards". They write: "Importantly, assessment of the right ventricle should form an integral component of risk assessment in athletes presenting with potentially lethal rhythm disturbances. Until only recently considered to be a Pandora's box of spurious and detrimental public messages, the right ventricle and its potential for adverse remodelling is increasingly acknowledged to represent the true Achilles' heel of the endurance athlete."

INFORMATION:

Notes:

[1] "Exercise-induced right ventricular dysfunction is associated with ventricular arrhythmias in endurance athletes", by André La Gerche et al. European Heart Journal. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv202

[2] "Arrhythmogenic right ventricular remodelling in endurance athletes: Pandora's box or Achilles' heel?" by Abbas Zaidi and Sanjay Sharma. European Heart Journal. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv199