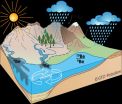

(Press-News.org) Over geologic time, the work of rain and other processes that chemically dissolve rocks into constituent molecules that wash out to sea can diminish mountains and reshape continents.

Scientists are interested in the rates of these chemical weathering processes because they have big implications for the planet's carbon cycle, which shuttles carbon dioxide between land, sea, and air and influences global temperatures.

A new study, published online on June 8 in the journal Nature Geoscience, by a team of scientists from Stanford and Germany's GFZ Research Center for Geosciences reveals that, contrary to expectations, weathering rates over the past 2 million years do not appear to have varied significantly between glacial and interglacial periods.

Scientists expect weathering rates to slow down during Earth's ice ages because temperatures were lower, and as a consequence much of the water that might fall as rain is trapped as ice in glaciers blanketing Europe and North America.

"If you look at how these attributes of climate control weathering rates today, you would expect that weathering and sedimentation rates can vary widely between glacial to interglacial times," said study author Friedhelm von Blanckenburg, a geochemist at the German Research Centre for Geosciences GFZ Potsdam.

For example, North America's Sierra Nevada mountain range is pockmarked by U-shaped valleys that were carved out by ice sheets during their relentless march southward in glacial times. When temperatures warmed, the ice sheets retreated, exposing pulverized rocks in the crater that could be easily weathered and transported out to sea by rivers and streams. Even in regions not covered by glaciers, scientists know that rainfall changed between glacial and interglacial times. Studies of now-dry lakebeds that once dotted the western U.S. and cone-shaped sedimentation deposits, called alluvial fans, from ancient rivers suggest water flow varied widely as temperature and rainfall patterns waxed and waned between ice ages and the warmer periods that followed.

But all of these lines of evidence testified only to local variations of weathering and sedimentation rates. "If you want to know the global weathering rate," von Blanckenburg said, "you have to go to the oceans, where local variations rates are averaged out."

von Blanckenburg and his colleague, Julien Bouchez, a research scientist at the Global Institue of Physics in Paris, turned to a geochemical technique that compares the concentration of two forms, or isotopes, of the element beryllium (Be). 9Be is found naturally in silicate rocks on Earth; 10Be is a radioactive cosmogenic isotope produced by the collision of cosmic rays with nitrogen and oxygen molecules in the atmosphere.

"Because 10Be rains down onto Earth's continents and oceans at more or less a constant rate, it's like a clock that can be used to time processes," von Blanckenburg said. "9Be, on the other hand, can be used to calculate how much dissolved rock has washed into the oceans from rivers."

By determining the ratio of 10Be to 9Be in marine sediment layers, von Blanckenburg was able to reconstruct the weathering flux for nearly the entire Quaternary Period, a timespan encompassing 2.6 million years. To his surprise, he found that there was little change between glacial and interglacial periods.

To understand why, von Blanckenburg teamed up with Stanford researchers Kate Maher, an assistant professor of geological sciences, and graduate student Daniel Ibarra, who specialize in using computer models to understand how the flow of water controls weathering. Maher and Ibarra compiled data about river-to-ocean flow from an ensemble of climate models and calculated the average discharge from rivers at different latitudes during glacial and interglacial times.

The Stanford scientists reached the same conclusion that von Blanckenburg and Bouchez did using their beryllium ratio observations. "Our results suggested that globally the aggregate change in discharge from all the rivers was effectively zero between the glacial and interglacial times. That was surprising," Maher said.

The models offered a likely explanation for this: they showed that while the change in water discharge for rivers at higher latitudes in the northern hemisphere could vary wildly between glacial and interglacial times, the flux for rivers in the tropics-which remained temperate even during ice ages-did not change by more than a few percent.

"The tropics account for more than half of the river runoff globally, so they strongly moderate chemical weathering fluxes during global shifts in climate," Ibarra said. "Because weathering helps balance the global carbon cycle, that means the tropical weathering is a primary driver of atmospheric CO2 levels over very long time scales."

INFORMATION:

The global movement patterns of all four seasonal influenza viruses are illustrated in research published today in the journal Nature, providing a detailed account of country-to-country virus spread over the last decade and revealing unexpected differences in circulation patterns between viruses.

In the study, an international team of researchers led by the University of Cambridge and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and including all five World Health Organization (WHO) Influenza Collaborating Centres, report surprising differences between the various types ...

Sydney, Australia: Patterns of peak rainfall during storms will intensify as the climate changes and temperatures warm, leading to increased flash flood risks in Australia's urban catchments, new UNSW Australia research suggests.

Civil engineers from the UNSW Water Research Centre have analysed close to 40,000 storms across Australia spanning 30 years and have found warming temperatures are dramatically disrupting rainfall patterns, even within storm events.

Essentially, the most intense downpours are getting more extreme at warmer temperatures, dumping larger volumes ...

New York, NY, June 8, 2015 - Professional physician associations consider certain routine tests before elective surgery to be of low value and high cost, and have sought to discourage their utilization. Nonetheless, a new national study by researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center finds that despite these peer-reviewed recommendations, no significant changes have occurred over a 14-year period in the rates of several kinds of these pre-operative tests.

The results are to publish online on June 8, 2015 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

"Our findings suggest that professional ...

Both statin and nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs were associated with memory loss in the first 30 days after patients started taking the medications when compared with nonusers, but researchers suggest the association may have resulted because patients using the medications may have more contact with their physicians and therefore be more likely to detect any memory loss, according to an article published online by JAMA Internal Medicine.

Acute memory loss associated with the use of statins has been described in case reports and case studies, as well as in some studies, ...

Researchers at University of Helsinki, Finland, and Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, discovered previously uncharacterized mutational patterns in the human regulatory genome, especially in gastrointestinal tract cancers. The study was published in Nature Genetics.

The research led by Academy Professor Lauri Aaltonen and Professor Jussi Taipale, was based on study of more than two hundred whole genomes of colorectal cancer samples. The scientists detected a distinct accumulation of mutations specifically at sites where the proteins CTCF and cohesin bind the DNA.

Both ...

It's a notion that might be pulled from the pages of science-fiction novel - electronic devices that can be injected directly into the brain, or other body parts, and treat everything from neurodegenerative disorders to paralysis.

It sounds unlikely, until you visit Charles Lieber's lab.

A team of international researchers, led by Lieber, the Mark Hyman, Jr. Professor of Chemistry, an international team of researchers developed a method for fabricating nano-scale electronic scaffolds that can be injected via syringe. Once connected to electronic devices, the scaffolds ...

Genes linked to creativity could increase the risk of developing schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, according to new research carried out by researchers at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King's College London.

Previous studies have identified a link between creativity and psychiatric disorders such as bipolar disorder, but it has remained unclear whether this association is due to common genes. Published today in Nature Neuroscience, this new study lends support to the direct influence on creativity of genes found in people with schizophrenia ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - If you want people to choose healthier foods, emphasize the positive, says a new Cornell University study.

Published in the American Journal of Agricultural Economics, the Cornell Food and Brand Lab study showed that when it comes to nutrition education, dos work a lot better than don'ts. This is especially important when determining policies that encourage healthy eating.

Media note: A short video explaining the research, as well as an informational graphic and additional details about this research can be found at, http://foodpsychology.cornell.edu/OP/Hidden_Costs ...

This news release is available in French. A new joint study by researchers at the Montreal Neurological Institute and the Centre for the Study of Democratic Citizenship, both at McGill University, has cast some light on the brain mechanisms that support people's voting decisions. Evidence in the study shows that a part of the brain called the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (LOFC) must function properly if voters are to make choices that combine different sources of information about the candidates. The study found that damage to the LOFC leads people to base their vote ...

A new study gives insight into the mental health of children and teens with Down syndrome and the behavioral medications that medical caregivers sometimes prescribe for them.

The Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center study shows that teens and young adults between the ages of 12 and 21 were significantly more likely to be on psychotropic medications than children 5 to 11 years old. Among children less than 12, the odds of being on a psychotropic medication increased with age for all classes of medications studied. For 12 to 18 year olds, the odds of being on ...