(Press-News.org) Researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center and its Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center are reporting a potentially important discovery in the battle against one of the most devastating forms of leukemia that accounts for as many as one in five children with a particularly aggressive form of the disease relapsing within a decade.

In a cover story set to appear in the journal Cancer Cell online June 8, researchers at NYU Langone and elsewhere report that they have successfully halted and reversed the growth of certain cancerous white blood cells at the center of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or T-ALL, by stalling the action of a specific protein receptor found in abundance on the surface of T cells at the core of T-ALL.

In experiments in mice and human cells, researchers found that blocking CXCR4 -- a so-called homing receptor protein molecule that helps T cells mature and attracts blood cells to the bone marrow -- halted disease progression in bone marrow and spleen tissue within two weeks. The experiments also left white blood cells cancer free for more than 30 weeks in live mice. Further, the research team found that in mice bred to develop T-ALL, depleting levels of the protein to which CXCR4 binds (CXCL12) also stalled T-ALL progression.

Researchers say their study results for the first time "clearly establish CXCR4 signaling as essential for T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cell growth and disease progression."

"Our experiments showed that blocking CXCR4 decimated leukemia cells," says co-senior study investigator and NYU Langone cell biologist Susan Schwab, PhD.

Schwab, an assistant professor at NYU Langone and its Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine, says similar laboratory test plans are underway for more potent CXCR4 antagonists, most likely in combination with established chemotherapy regimens. She notes that anti-CXCR4 drugs are already in preliminary testing for treating certain forms of myeloid leukemia, and have so far proven to be well-tolerated, but such treatments have not yet been tried for T-ALL.

Schwab says T-ALL is "a particularly devastating cancer" because there are not many treatment options.

One American survey, she points out, showed that only 23 percent of patients lived longer than five years after failing to sustain remission with standard chemotherapy drugs.

Co-senior study investigator and cancer biologist Iannis Aifantis, PhD, says the study offers the first evidence that "drugs targeting and disrupting leukemia cells' microenvironment -- or what goes on around them -- could prove effective against the disease."

Aifantis, the chair of the Department of Pathology at NYU Langone and a member of its Perlmutter Cancer Center, and an early career scientist at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, says experiments in his laboratory had shown that leukemia-initiating cells concentrate in the bone marrow near CXCL12-producing blood vessels. This finding prompted a collaborative effort to investigate expression and function of CXCR4 because it binds to CXCL12, which in turn led to the researchers determining the vital role played by CXCR4-CXCL12 molecular signaling in disease growth.

Aifantis says more research needs to be done to decipher how CXCR4 is able to promote and sustain T-ALL.

As part of the new study, researchers deleted CXCL12 production specifically from bone marrow vasculature in leukemic mice. Disease progression in the bone marrow stalled within three weeks and tumors were smaller than in similar mice that retained CXCL12 production. Deletion of the CXCR4 gene led to sustained T-ALL remission within a month in similar mice, as well as movement of the cancerous blood cells away from the bone marrow. Subsequent transplant of millions of human T-ALL cells into normal mice that were then treated with an anti-CXCR4 drug induced remission within two weeks, with diseased spleen and bone marrow tissue nearly returning to normal.

INFORMATION:

Funding support for the study was provided by the U.S. National Cancer Institute, National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases -- all parts of the National Institutes of Health. Corresponding federal grant numbers are R01 CA133379, R01 CA105129, R01 CA149655, R01 CA173636, R01 CA169784, R01 GM088847, T32-CA009161-37, R01 AI085166, and P30 CA016087. Further funding support was provided by the William Lawrence and Blanche Hughes Foundation, the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (corresponding grant numbers TRP#6340 -11 and LLS#6373-13), the Chemotherapy Foundation, the Irma T. Hirschl Trust; the V Foundation for Cancer Research, the St. Baldrick's Foundation, the Children's Leukemia Research Foundation, and the Dana Foundation.

Besides Schwab and Aifantis, other NYU Langone researchers involved in these experiments were lead study investigators Lauren Pitt, PhD, and Anastasia Tikhonova, PhD; and study co-investigators Hai Hu, BS; Thomas Trimarchi, PhD; Bryan King, PhD; and Yixia Gong, PhD; Aris Tsirigos, PhD; and Dan Littman, MD, PhD. Additional research support was provided by Marta Sanchez-Martin, PhD, and Adolfo Ferrando, MD, PhD, at Columbia University in New York; Sean Morrison at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas; and David Fooksman, PhD, at Albert Einstein Medical College in New York.

For more information, go to:

http://www.med.nyu.edu/skirball-lab/schwablab/Home.html

http://www.aifantislab.com/

http://www.cell.com/cancer-cell/home

Media Contact:

David March

212-404-3528?david.march@nyumc.org

A research group at Disney Research Pittsburgh has developed a computer vision system that, much like humans, can continuously improve its ability to recognize objects by picking up hints while watching videos.

Like most other object recognition systems, the Disney system builds a conceptual model of an object, be it an airplane or a soap dispenser, by using a learning algorithm to analyze a number of example images of the object.

What's different about the Disney system is that it then uses that model to identify objects, when it can, in videos. As it does, it sometimes ...

An algorithm developed through collaboration of Disney Research Pittsburgh and Boston University can improve the automated recognition of actions in a video, a capability that could aid in video search and retrieval, video analysis and human-computer interaction research.

The core idea behind the new method is to express each action, whether it be a pedestrian strolling down the street or a gymnast performing a somersault, as a series of space-time patterns. These begin with elementary body movements, such as a leg moving up or an arm flexing. But these movements also ...

URBANA, Ill. - Contrary to popular belief, foreclosed properties do not always lead to unkempt lawns. University of Illinois researchers used remote sensing technology to observe rapid change in U.S. urban settings, specifically homes in Maricopa County, Arizona, that foreclosed over about a 10-year period.

"We learned that when a property is foreclosed, it's more nuanced than nature just coming in and taking over," said U of I professional geographer Bethany Cutts. "Foreclosure doesn't always mean management stops."

Cutts said the team of researchers chose to test ...

Tropical Cyclone 01A has been moving in a northerly direction through the Northern Indian Ocean, and is now curving to the west, moving into the Gulf of Oman. NASA's Aqua satellite and RapidScat instruments gathered imagery and data on the storm. Three days of RapidScat imagery showed how sustained winds increased around the entire storm.

The first tropical cyclone of the Northern Indian Ocean Season was born on Sunday, June 7. Tropical Cyclone 1A developed near 16.3 North latitude and 68.5 East longitude, about 536 nautical miles (616.8 miles/992.7 km) south of Karachi, ...

Raising healthy chicks is always a challenge, but in a cold, fish-free Arctic lake, it's an enormous undertaking. Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata) parents must constantly fly back and forth between their nesting lakes and the nearby ocean, bringing back fish to feed their growing young, and a new study suggests that the chicks grow fast and fledge while they're still small so that they can reach the food-rich ocean themselves and give their parents a break.

Growing chicks must take in enough energy to move around, grow, and maintain their body temperature. The bigger ...

That weathering has to do with the weather is obvious in itself. All the more astonishing, therefore, are the research results of a group of scientists from the GFZ German Research Center for Geosciences in Potsdam and Stanford University, USA, which show that variations in the weathering of rocks over the past 2 million years have been relatively uniform despite the distinct glacial and interglacial periods and the associated fluctuations in the Earth's climate.

The researchers have observed a most stable behavior in marine sediments, fed year after year through the ...

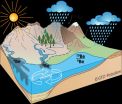

Over geologic time, the work of rain and other processes that chemically dissolve rocks into constituent molecules that wash out to sea can diminish mountains and reshape continents.

Scientists are interested in the rates of these chemical weathering processes because they have big implications for the planet's carbon cycle, which shuttles carbon dioxide between land, sea, and air and influences global temperatures.

A new study, published online on June 8 in the journal Nature Geoscience, by a team of scientists from Stanford and Germany's GFZ Research Center for Geosciences ...

The global movement patterns of all four seasonal influenza viruses are illustrated in research published today in the journal Nature, providing a detailed account of country-to-country virus spread over the last decade and revealing unexpected differences in circulation patterns between viruses.

In the study, an international team of researchers led by the University of Cambridge and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, and including all five World Health Organization (WHO) Influenza Collaborating Centres, report surprising differences between the various types ...

Sydney, Australia: Patterns of peak rainfall during storms will intensify as the climate changes and temperatures warm, leading to increased flash flood risks in Australia's urban catchments, new UNSW Australia research suggests.

Civil engineers from the UNSW Water Research Centre have analysed close to 40,000 storms across Australia spanning 30 years and have found warming temperatures are dramatically disrupting rainfall patterns, even within storm events.

Essentially, the most intense downpours are getting more extreme at warmer temperatures, dumping larger volumes ...

New York, NY, June 8, 2015 - Professional physician associations consider certain routine tests before elective surgery to be of low value and high cost, and have sought to discourage their utilization. Nonetheless, a new national study by researchers at NYU Langone Medical Center finds that despite these peer-reviewed recommendations, no significant changes have occurred over a 14-year period in the rates of several kinds of these pre-operative tests.

The results are to publish online on June 8, 2015 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

"Our findings suggest that professional ...