(Press-News.org) Cutaneous melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, is now believed to be divided into four distinct genomic subtypes, say researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, a finding that could prove valuable in the ever-increasing pursuit of personalized medicine.

As part of The Cancer Genome Atlas, researchers identified four melanoma subtypes: BRAF, RAS, NF1 and Triple-WT, which were defined by presence or absence of mutations from analysis of samples obtained from 331 patients. The five-year study resulted from an international collaboration of over 300 researchers from more than five countries, including Australia, Germany and Canada.

'A major achievement in the clinical management of patients with advanced melanoma has been the development of effective targeted therapies,' said Jeffrey E. Gershenwald, M.D., professor of surgery, Surgical Oncology. 'This comprehensive classification of melanomas allows us to create a framework that could be used to further personalize therapeutic decision-making in both the targeted and immunotherapy arena, as well as to develop more impactful prognostic and predictive models to inform patient care.'

Results from the study are published in the June 18 issue of Cell. Analysis of the TCGA effort was chaired by Gershenwald, Ian Watson, Ph.D., instructor of Genomic Medicine and Lynda Chin, M.D., former chair of Genomic Medicine and now associate vice chancellor for health transformation and chief innovation officer for health affairs at The UT System. Gershenwald is also co-leader of MD Anderson's Melanoma Moon Shot Program, which aims to accelerate the conversion of scientific discoveries into clinical advances and significantly reduce cancer deaths.

The scientists found all four genomic subtypes share common 'downstream' signaling pathways, but differ in how they activate these pathways. Understanding the genomic underpinnings of melanoma may provide additional information on other existing therapies.

'For example, BRAF and MEK inhibitor combinations are now used to treat patients with BRAF mutant melanomas, and MEK inhibitor combinations are being explored for RAS mutant melanomas,' said Watson. 'Pre-clinical studies have already demonstrated that some NF1 melanoma cell lines respond to MEK inhibitors, but more work is needed to identify responders and non-responders within this new melanoma subtype, as well as to determine strategies to treat Triple Wild-type melanoma patients.'

Interestingly, no significant correlation was found between the genomic subtypes and patient outcome. However, within each genomic subtype, they found a subset with evidence of immune infiltration that did correlate with improved survival.

'Detailed analyses showed that these lymphocytic elements were not merely 'bystanders,'' said Chin. 'They had infiltrated the tumor and were likely associated with melanoma biology.' The study also revealed the importance of a T cell biomarker called LCK, a protein found in lymphocytes or white blood cells. The biomarker was shown to be associated with improved patient survival.

The team hypothesizes that this information could prove useful in the emerging field of immunotherapy, which has shown success in treating late-stage melanoma patients. In particular, recently approved checkpoint blockade drugs have shown incredible potential in treatment for melanomas. Yet, it is not entirely clear which patients respond to the therapy.

'We believe this international collaboration from more than 20 tissue source sites and 50 institutions around the globe, which included pathologists who analyzed samples for immune infiltration, computational biologists who identified significant driving genetic alterations, and clinician scientists who aided in acquiring samples and interpreting data, have generated a dataset that is a treasure trove, and that will seed studies for many years to come,' said Chin. 'We could not have carried out this study without the families and patients who donated samples by participating in research protocols.'

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (U54HG003273, U54HG003067, U54HG003079, U24CA143799, U24CA143835, U24CA143840, U24CA143843, U24CA143845, U24CA143848, U24CA143858, U24CA143866, U24CA143867, U24CA143882, U24CA143883, U24CA144025, and P30CA016672.

PHILADELPHIA -- Most of us need seven to eight hours of sleep a night to function well, but some people seem to need a lot less sleep. The difference is largely due to genetic variability. In research published online June 18th in Current Biology, researchers report that two genes, originally known for their regulation of cell division, are required for normal slumber in fly models of sleep: taranis and Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1).

'There's a lot we don't understand about sleep, especially when it comes to the protein machinery that initiates the process on the ...

In 2012, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine showed that heart muscle cells made from the skin of people with a cardiac condition called dilated cardiomyopathy beat with less force than those made from the skin of healthy people. These cells also responded less readily to the waves of calcium that control the timing and strength of each contraction.

Now, the same research team has teased apart the molecular basis for these differences and identified a drug treatment that at least partially restores function to diseased cells grown in a laboratory ...

Adult neural stem cells, which are commonly thought of as having the ability to develop into many type of brain cells, are in reality pre-programmed before birth to make very specific types of neurons, at least in mice, according to a study led by UC San Francisco researchers.

"This work fundamentally changes the way we think about stem cells," said principal investigator Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, UCSF professor of neurological surgery, Heather and Melanie Muss Endowed Chair and a principal investigator in the UCSF Brain Tumor Research Center and the Eli and Edythe Broad ...

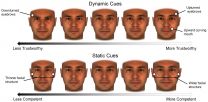

We can alter our facial features in ways that make us look more trustworthy, but don't have the same ability to appear more competent, a team of New York University psychology researchers has found.

The study, which appears in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, a SAGE journal, points to both the limits and potential we have in visually representing ourselves--from dating and career-networking sites to social media posts.

"Our findings show that facial cues conveying trustworthiness are malleable while facial cues conveying competence and ability are significantly ...

Want to lose abdominal fat, get smarter and live longer? New research led by USC's Valter Longo shows that periodically adopting a diet that mimics the effects of fasting may yield a wide range of health benefits.

In a new study, Longo and his colleagues show that cycles of a four-day low-calorie diet that mimics fasting (FMD) cut visceral belly fat and elevated the number of progenitor and stem cells in several organs of old mice -- including the brain, where it boosted neural regeneration and improved learning and memory.

The mouse tests were part of a three-tiered ...

Last June, in the early days of the Ebola outbreak in Western Africa, a team of researchers sequenced the genome of the deadly virus at unprecedented scale and speed. Their findings revealed a number of critical facts as the outbreak was unfolding, including that the virus was being transmitted only by person-to-person contact and that it was picking up new mutations through its many transmissions.

While public health officials now believe the worst of the epidemic is behind us, it is not yet over, and questions raised by the previous work still await answers.

To ...

PHILADELPHIA - Several well-known neurodegenerative diseases, such as Lou Gehrig's (ALS), Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Huntington's disease, all result in part from a defect in autophagy - one way a cell removes and recycles misfolded proteins and pathogens. In a paper published this week in Current Biology, postdoctoral fellow David Kast, PhD, and professor Roberto Dominguez, PhD, and three other colleagues from the Department of Physiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, show for the first time that the formation of ephemeral compartments ...

University of California San Francisco scientists have identified characteristics of a family of daughter cells, called MPPs, which are the first to arise from stem cells within bone marrow that generate the entire blood system. The researchers said the discovery raises the possibility that, by manipulating the fates of MPPs or parent stem cells, medical researchers could one day help overcome imbalances and deficiencies that can arise in the blood system due to aging or in patients with specific types of leukemia.

Similar imbalances can render patients vulnerable immediately ...

PORTLAND, Ore. -- Advancing the field of structural biology that underpins how things work in a cell, researchers have identified how proteins change their shape when performing specific functions. The study's fresh insights, published online in the journal Structure, provide a more complete picture of how proteins move, laying a foundation of understanding that will help determine the molecular causes of human disease and the development of more potent drug treatments.

Though it has long been recognized that proteins are not static, for more than 30 years, scientists' ...

The secret to preventing HIV infection lies within the human immune system, but the more-than-25-year search has so far failed to yield a vaccine capable of training the body to neutralize the ever-changing virus. New research from The Rockefeller University, and collaborating institutions, suggests no single shot will ever do the trick. Instead, the scientists find, a sequence of immunizations might be the most promising route to an HIV vaccine.

Scientists have thought for some time that multiple immunizations, each tailored to specific stages of the immune response, ...