(Press-News.org) For cell division to be successful, pairs of chromosomes have to line up just right before being swept into their new cells, like the opening of a theater curtain. They accomplish this feat in part thanks to structures called centrioles that provide an anchor for the curtain's ropes. Researchers at Johns Hopkins recently learned that most cells will not divide without centrioles, and they found out why: A protein called p53, already known to prevent cell division for other reasons, also monitors centriole numbers to prevent potentially disastrous cell divisions.

Details of the findings will be published online in the Journal of Cell Biology on July 6. The new information, plus new tools for centriole manipulation, should help researchers figure out how p53 helps safeguard cells -- and how it causes cancers when it doesn't.

"P53 was already known to monitor many things, like DNA damage and having the wrong number of chromosomes, that make division dangerous for cells," says Andrew Holland, Ph.D., an assistant professor of molecular biology and genetics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "We've discovered one more item on its checklist: centriole number."

Cells normally have two centrioles that work together as a unit to anchor and organize microtubules, the molecular rods that form the cell's backbone. As a cell prepares for division, one new centriole forms alongside each existing centriole. Then, each pair goes to opposite sides of the cell. Before dividing, pairs of identical chromosomes line up in the middle of the elongated cell, and the microtubules, emanating out from the centrioles on either side, help pull the chromosomes in opposite directions so that each new cell receives one member of each chromosome pair.

"If cells don't segregate their chromosomes properly, there can be dire consequences," says Bramwell Lambrus, a graduate student in Holland's laboratory. "Down syndrome, for example, results from an embryo inheriting an extra copy of chromosome 21. What's fascinating is that the cells that divide to create a woman's egg cells do not have centrioles, so we know that they're not absolutely necessary but very helpful."

To better understand the role of centrioles in cell division, the team needed to see how cells behaved without them. However, fully wiping out a cell's centrioles for long enough to study the results posed a serious challenge because, when a cell senses its centrioles are gone, it makes new ones from scratch. To overcome this hurdle, Holland's team went after the protein Plk4, which is required for centriole formation. Instead of permanently deleting the Plk4 gene from the cells, they used a trick from plant biology to toggle its presence in the cells -- one that had never before been applied to an animal cell's proteins.

Working with human retina cells, the researchers tweaked Plk4 so that it would be sent to cellular trash cans whenever they gave the cells a plant hormone called auxin. As long as it was present, auxin prevented new centrioles from forming, so each cell division halved the number of centrioles per cell. By the fourth cell division, most of the cells had no centrioles, and none of them divided again. But even after auxin was removed and Plk4 was restored, the cells refused to divide or make more centrioles.

"The cells were permanently stuck," explains Holland. "It was a Catch-22. They couldn't divide again without making new centrioles, but they couldn't make new centrioles without starting the process of division. It was clear that something was telling the cells not to divide."

After testing a few different hypotheses to explain why the cells were stuck, the team turned to p53, a protein known for preventing cell division when things aren't right. When they halted p53 production in cells with no centrioles, they began to divide again. As expected, the newly formed cells had many chromosome abnormalities.

In a final experiment, the scientists restored Plk4 to cells lacking both centrioles and p53 to see if the cells would make new centrioles. Since p53 wasn't there to prevent their division, the return of Plk4 was all that was necessary for the cells to start centriole formation again from scratch. "Since centriole formation without an existing centriole template only occurs when cells lack all of their centrioles, it's a rare occurrence, and it was exciting to watch it happen under the microscope," says Lambrus.

The team plans to continue analyzing the formation of new centrioles, and how p53 detects centrioles and prevents cells from dividing without them. "Ninety percent of human tumors have chromosome abnormalities, and we know that many of these are made possible by mutations in p53," says Holland. "If centrioles aren't there to aid proper chromosome segregation, p53 acts as backup to prevent making abnormal cells. It's an important safeguard that we'd like to understand more."

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the report include Kevin Clutario, Vikas Daggubati and Michael Snyder of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; and Yumi Uetake and Greenfield Sluder of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

This work was supported by the Leukemia Research Foundation, a W.W. Smith Charitable Trust research grant, a March of Dimes Basil O'Conner Scholar Award, a Pew Scholar Award and a Kimmel Scholar Award.

Richland, Wash. -- Despite decades of industrial use, the exact chemical transformations occurring within zeolites, a common material used in the conversion of oil to gasoline, remain poorly understood. Now scientists have found a way to locate--with atomic precision--spots within the material where chemical reactions take place, and how these spots shut down.

Called active sites, the spots help rip apart and rearrange molecules as they pass through nanometer-sized channels, like an assembly line in a factory. A process called steaming causes these active sites to cluster, ...

Anti-inflammatory drug is one thousandth of the cost of the current drug which works in the same way

Discovery may open up cost effective treatment options not just for the NHS but also cancer patients across the world

Scientists at the University of Sheffield have discovered that a common drug given to arthritis sufferers could also help to treat patients with blood cancers.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) are diagnosed in around 3,300 UK patients every year and cause an overproduction of blood cells creating a significant impact on quality-of-life, with symptoms ...

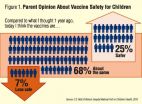

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- Over the same time period that multiple outbreaks of measles and whooping cough made headlines around the country, parents' views on vaccines became more favorable, according to a new nationally-representative poll.

The University of Michigan C.S. Mott Children's Hospital National Poll on Children's Health asked parents in May how their views on vaccinations changed between 2014 and 2015 - during which two dozen measles outbreaks were reported in the U.S., including a multi-state outbreak traced to Disneyland.

One-third of parents who participated ...

A spider's web is one of the most intricate constructions in nature, but its precious silk has more than one use. Silk threads can be used as draglines, guidelines, anchors, pheromonal trails, nest lining, or even food. And each use requires a slightly different type of silk, optimized for its function.

"Each type of silk has similar proteins, but they are synthesized differently," said Sinan Keten, assistant professor of mechanical and civil engineering at Northwestern University's McCormick School of Engineering. "Then the spider knows how fast to reel the silk to get ...

An ambitious policy package is essential for the UK to transform its energy system to achieve the deep reductions in carbon emissions required to avoid dangerous climate change, according to research led by UCL scientists. To meet climate targets set for 2050, policies need to ensure strong action is taken now, while preparing for fundamental changes in how energy is provided and used in the long term.

The study is part of the Deep Decarbonization Pathway Project (DDPP) which is coordinated by the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI) ...

It may sound counter-intuitive, but crushing up bees into a 'DNA soup' could help conservationists understand and even reverse their decline - according to University of East Anglia scientists.

Research published today in the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution shows that collecting wild bees, extracting their DNA, and directly reading the DNA of the resultant 'soup' could finally make large-scale bee monitoring programmes feasible.

This would allow conservationists to detect where and when bee species are being lost, and importantly, whether conservation interventions ...

BARCELONA-LUGANO, 4 July 2015 - Patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) that are mutation-free in the KRAS, NRAS, BRAF and PIK3CA genes showed significant benefit from continuing anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy beyond progression following first-line chemotherapy and an anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody, according to study results (1) presented today at the ESMO 17th World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer in Barcelona, Spain.

Prof Fortunato Ciardiello from Seconda Università degli Studi di Napoli, Italy, presented results from the CAPRI-Goim ...

Mice that are exposed to the powerful smell of cat urine early in life do not escape from cats later in life. Researchers at the A. N. Severtsov Institute of Ecology and Evolution, Russia, have discovered that mice that smell cat urine early in life, do not avoid the same odour, and therefore do not escape from their feline predators, later in life.

"Because the young mice (less than 2 weeks-old) are being fed milk while being exposed to the odour, they experience positive reinforcement," says Dr Vera Voznessenskaya, one of the lead researchers behind this study. "So ...

To mark the final day of the 65th Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting, on Friday, 3 July, over 30 Nobel laureates assembled on Mainau Island on Lake Constance signed a declaration on climate change. The "Mainau Declaration 2015 on Climate Change" states "that the nations of the world must take the opportunity at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris in December 2015 to take decisive action to limit future global emissions." It is expected that a new international agreement on climate protection will be approved at the 21st UN Climate Conference to succeed the ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- The brain hidden inside the oldest known Old World monkey skull has been visualized for the first time. The creature's tiny but remarkably wrinkled brain supports the idea that brain complexity can evolve before brain size in the primate family tree.

The ancient monkey, known scientifically as Victoriapithecus, first made headlines in 1997 when its fossilized skull was discovered on an island in Kenya's Lake Victoria, where it lived 15 million years ago.

Now, thanks to high-resolution X-ray imaging, researchers have peered inside its cranial cavity ...