INFORMATION:

Additional Georgetown co-authors include Kamal P. Sajwan, Saravana P. Selvanathan, PhD, Benjamin J. Marsh, Amrita V. Pai, Yasemin Saygideger Kont, MD, Jenny Han, Tsion Z. Minas, Said Rahim, PhD, Hayriye Verda Erkizan, PhD and Jeffrey A. Toretsky, MD.

A Department of Defense Synergistic Idea Development Award (W81XWH-10-1-0137) funded the study.

Georgetown University has filed a patent application for using NSC305787 and related compounds to inhibit ezrin function and for the treatment of cancer. Üren and Toretsky are listed as inventors.

About Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center

Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, part of Georgetown University Medical Center and MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, seeks to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer through innovative basic and clinical research, patient care, community education and outreach, and the training of cancer specialists of the future. Georgetown Lombardi is one of only 41 comprehensive cancer centers in the nation, as designated by the National Cancer Institute (grant #P30 CA051008), and the only one in the Washington, DC area. For more information, go to http://lombardi.georgetown.edu.

About Georgetown University Medical Center

Georgetown University Medical Center (GUMC) is an internationally recognized academic medical center with a three-part mission of research, teaching and patient care (through MedStar Health). GUMC's mission is carried out with a strong emphasis on public service and a dedication to the Catholic, Jesuit principle of cura personalis -- or "care of the whole person." The Medical Center includes the School of Medicine and the School of Nursing & Health Studies, both nationally ranked; Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute; and the Biomedical Graduate Research Organization, which accounts for the majority of externally funded research at GUMC including a Clinical and Translational Science Award from the National Institutes of Health.

Protein implicated in osteosarcoma's spread acts as air traffic controller

2015-07-06

(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON (July 6, 2015) -- The investigation of a simple protein has uncovered its uniquely complicated role in the spread of the childhood cancer, osteosarcoma. It turns out the protein, called ezrin, acts like an air traffic controller, coordinating multiple functions within a cancer cell and allowing it to endure stress conditions encountered during metastasis.

It's been known that ezrin is a key regulator of osteosarcoma's spread to the lungs, but its mechanism was not known. Osteosarcoma is a tumor of bone that afflicts children, adolescents and young adults. In most cases, the tumor is localized in the extremities and can be completely removed by surgery or amputation.

"The main cause of death in osteosarcoma patients is not the tumor on their limbs, but the failure of their lungs when the cancer spreads there," explains Aykut Üren, MD, professor of oncology at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Üren and his colleagues have developed molecules that block ezrin's function and prevent osteosarcoma spread in mouse models. In an attempt to explain the molecular mechanisms underlying ezrin-mediated cancer metastasis, the researchers discovered this previously unrecognized role for ezrin. Their finding is published online today in the journal Molecular and Cellular Biology.

"Conventionally ezrin was believed to be functioning only on the inner surface of cancer cells," Üren says, "but our new discovery indicates that ezrin may operate deeper in the core of the cell and regulate expression of critical genes that are important for cancer's spread."

The scientists say that ezrin functions in a new capacity that is unusual for its family of proteins. They found that ezrin's unusual interaction with another protein called DDX3 results in modulation of genes that give cancer cells an edge in surviving harsh conditions.

"Knowing exactly how ezrin works will help our team develop the ezrin-targeting small molecules as potential new drugs to prevent the spread of cancer cells to lungs in osteosarcoma patients," Uren says.

"Implications of our findings go beyond cancer research," says the study's first author Haydar Çelik, PhD. "Because this work suggests a new molecular mechanism on how ezrin is involved in the regulation of mRNA translation, these observations may provide important clues for scientists investigating how viruses enter and replicate in human cells too."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Link found between autoimmune diseases, medications, and a dangerous heartbeat condition

2015-07-06

Mohamed Boutjdir, PhD, professor of medicine, cell biology, and physiology and pharmacology at SUNY Downstate Medical Center, has led a study with international collaborators identifying the mechanism by which patients with various autoimmune and connective tissue disorders may be at risk for life-threatening cardiac events if they take certain anti-histamine or anti-depressant medications. Dr. Boutjdir is also director of the Cardiac Research Program at VA New York Harbor Healthcare System.

The researchers published their findings in the online edition of the American ...

Stress-fighting proteins could be key to new treatments for asthma

2015-07-06

Investigators have discovered the precise molecular steps that enable immune cells implicated in certain forms of asthma and allergy to develop and survive in the body. The findings from Weill Cornell Medical College reveal a new pathway that scientists could use to develop more effective treatments and therapies for the chronic lung disorder.

More than 1 in 12 Americans are affected by asthma, a disorder characterized by an overactive immune response to normally harmless substances such as pollen or mold. Scientists had previously discovered that an overabundance of ...

Restraint and confinement still an everyday practice in mental health settings

2015-07-06

Providers of mental-health services still rely on intervention techniques such as physical restraint and confinement to control some psychiatric hospital patients, a practice which can cause harm to both patients and care facilities, according to a new study from the University of Waterloo.

The study, which appears in a special mental health issue of Healthcare Management Forum, found that almost one in four psychiatric patients in Ontario hospitals are restrained using control interventions, such as chairs that prevent rising, wrist restraints, seclusion rooms or acute ...

Older patients with spinal cord injury: Surgery less likely than for younger patients

2015-07-06

Older patients with traumatic spinal cord injury are less likely than younger patients to receive surgical treatment and experience a significant lag between injury and surgery, according to new research in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal)

The number of people with traumatic spinal cord injury over age 70 is increasing, and it is projected that people in this age group will eventually make up the majority of those with new spinal cord injuries. Currently, most spinal cord injuries occur in people aged 16 to 30 years.

To determine whether patients over age ...

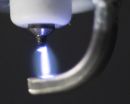

Mass. General team generates therapeutic nitric oxide from air with an electric spark

2015-07-06

Treatment with inhaled nitric oxide (NO) has proven to be life saving in newborns, children and adults with several dangerous conditions, but the availability of the treatment has been limited by the size, weight and complexity of equipment needed to administer the gas and the therapy's high price. Now a research team led by the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) physician who pioneered the use of inhaled nitric oxide has developed a lightweight, portable system that produces NO from the air by means of an electrical spark. The investigators describe their invention in ...

Uncovering the mechanism of our oldest anesthetic

2015-07-06

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Nitrous oxide, commonly known as "laughing gas," has been used in anesthesiology practice since the 1800s, but the way it works to create altered states is not well understood. In a study published this week in Clinical Neurophysiology, MIT researchers reveal some key brainwave changes among patients receiving the drug.

For a period of about three minutes after the administration of nitrous oxide at anesthetic doses, electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings show large-amplitude slow-delta waves, a powerful pattern of electrical firing that sweeps across ...

How to rule a gene galaxy: A lesson from developing neurons

2015-07-06

The human organism contains hundreds of distinct cell types that often differ from their neighbours in shape and function. To acquire and maintain its characteristic features, each cell type must express a unique subset of genes. Neurons, the functional units of our brain, develop through differentiation of neuronal precursors, a process that depends on coordinated activation of hundreds and possibly thousands of neuron-specific genes.

A new study published in Nature Communications by researchers from the MRC Centre for Developmental Neurobiology (MRC CDN) at IoPPN, carried ...

New paradigm for treating 'inflammaging' and cancer

2015-07-06

Intermittent dosing with rapamycin selectively breaks the cascade of inflammatory events that follow cellular senescence, a phenomena in which cells cease to divide in response to DNA damaging agents, including many chemotherapies. The finding, published in Nature Cell Biology, shows that once disrupted, it takes time for the inflammatory loop to reestablish, providing proof-of-principal that intermittent dosing could provide a way to reap the benefits of rapamycin, an FDA-approved drug that extends lifespan and healthspan in mice, while lessening safety issues associated ...

Extra DNA acts as a 'spare tire' for our genomes

2015-07-06

Carrying around a spare tire is a good thing -- you never know when you'll get a flat. Turns out we're all carrying around "spare tires" in our genomes, too. Today, in ACS Central Science, researchers report that an extra set of guanines (or "G"s) in our DNA may function just like a "spare" to help prevent many cancers from developing.

Various kinds of damage can happen to DNA, making it unstable, which is a hallmark of cancer. One common way that our genetic material can be harmed is from a phenomenon called oxidative stress. When our bodies process certain chemicals ...

Risk of interbreeding due to climate change lower than expected

2015-07-06

One of the questions raised by climate change has been whether it could cause more species of animals to interbreed. Two species of flying squirrel have already produced mixed offspring because of climate change, and there have been reports of a hybrid polar bear and grizzly bear cub (known as a grolar bear, or a pizzly).

"Climate change is causing species' ranges to shift, and that could bring a lot of closely related species into contact," said Meade Krosby, a research scientist in the University of Washington's Climate Impacts Group.

She is the lead author of a ...