(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON, DC - July 15, 2015 - For decades, researchers have worked to improve cacao fermentation by controlling the microbes involved. Now, to their surprise, a team of Belgian researchers has discovered that the same species of yeast used in production of beer, bread, and wine works particularly well in chocolate fermentation. The research was published ahead of print July 6th in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a publication of the American Society for Microbiology.

"Chemical analyses as well as tasting the chocolate showed that the chocolate produced with our best yeasts is much better and more consistent than the chocolate produced through natural fermentation," said Kevin Verstrepen, PhD, professor of genetics and genomics, the University of Leuven, and the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology (VIB), Belgium. "Moreover, different yeasts yielded different chocolate flavors, indicating that it would be possible to create a whole range of specialty chocolates to match everyone's favorite flavor."

After the harvest, cacao beans are collected and placed in large wooden boxes, or even piled on the soil at the farms where they are grown, said Verstrepen. At this point, the beans are surrounded by an unappetizing white, gooey, pulp composed of sugars, proteins, water, pectin, and small amounts of lignin and hemicellulose. Microbes that are present in the farm environment then go to work consuming the pulp through fermentation.

Differences among the microbes at different farms result in differences in flavor and quality of the resulting chocolate, said Verstrepen. "Some microbes produce bad aromas that enter into the beans, giving rise to chocolate with a foul taste, while others do not fully consume the pulp, making the resulting beans difficult to process."

"We were looking to find or develop the best microbes that result in the best chocolate," said Verstrepen. These, he said, could be added immediately at the onset of fermentation, allowing them to outcompete less desirable microbes, enabling consistent production of high quality chocolate.

However, finding strains that could outcompete the undesirables and produce high quality chocolate proved highly challenging. The investigators characterized more than 1,000 strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mostly from the alcoholic beverage industry, but including some from cacao farms. Some of the best performers came from the latter, and others came from the beer, wine, bioethanol, and sake industries, said Verstrepen. A key to success was the ability to tolerate the high temperatures encountered during cocoa fermentation--45°-50° centigrade (107.6°-109.4° Fahrenheit).

The investigators then crossed some of the best strains, to produce hybrids which they found performed even better. "The rationale behind this approach is identical to breeding strategies in agriculture: crossing optimal strains can generate superior offspring," says coauthor Jan Steensels, group leader for industrial research, and Ph.D. student at the Flanders Institute for Biotechnology. Compared to crossing livestock or crop plants, crossing yeasts is technically more challenging, and requires highly accurate microscopy, said Verstrepen.

The investigators then applied these new hybrids to fermenting chocolate on farms, which their industrial partner, Barry-Callebaut used to make chocolate for the taste testing. "In these tests, the (very eager) consumers' panel voted unanimously for chocolate derived from beans fermented by the newly developed yeast strains," said Steensels. Barry-Callebaut now plans commercial production of a range of tailor-made chocolates, using some of the novel yeasts.

INFORMATION:

This article can be found online at http://aem.asm.org/cgi/reprint/AEM.00133-15v1?ijkey=jE33fWG5lFxnI&keytype=ref&siteid=asmjournals.

The American Society for Microbiology is the largest single life science society, composed of over 39,000 scientists and health professionals. Its mission is to advance the microbiological sciences as a vehicle for understanding life processes and to apply and communicate this knowledge for the improvement of health and environmental and economic well-being worldwide.

LAWRENCE -- American media in effort to highlight a diverse set of voices in covering politics generally over-represent the amount of people who contribute to policy making when compared with journalists in South Korea.

A University of Kansas researcher made the findings as part of a recent study that examined how government officials were treated in front-page news coverage between the two free-press nations. The article by Jiso Yoon, a KU assistant professor of political science, and co-author Amber Boydstum, an assistant professor of political science at the University ...

AURORA, Colo. (July 15, 2015) - Physicians at the University of Colorado School of Medicine on the Anschutz Medical Campus have published research that suggests a safe and lower-cost way to diagnose and treat problems in the upper gastrointestinal tract of children.

The researchers assessed the effectiveness of unsedated transnasal endoscopy (TNE) in evaluating pediatric patients with potentially chronic problems in their esophagus, which is the tube that connects the patient's mouth to the stomach. The research team included Joel A. Friedlander, DO, MA-Bioethics, Jeremy ...

The human genome encodes roughly 20,000 genes, only a few thousand more than fruit flies. The complexity of the human body, therefore, comes from far more than just the sequence of nucleotides that comprise our DNA, it arises from modifications that occur at the level of gene, RNA and protein.

In a new study, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine show how one of these modifications, which occurs after RNA is translated into proteins, has the power to greatly influence the function of an enzyme called PRPS2, which is required for ...

Athens, Ga. - Researchers from the University of Georgia have determined that various freshwater sources in Georgia, such as rivers and lakes, could feature levels of salmonella that pose a risk to humans. The study is featured in the July edition of PLOS One.

Faculty and students from four colleges and five departments at UGA partnered with colleagues from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Georgia Department of Public Health to establish whether or not strains of salmonella exhibit geographic trends that might help to explain differences in rates ...

DURHAM, N.C. - Children with even mild or passing bouts of depression, anxiety and/or behavioral issues were more inclined to have serious problems that complicated their ability to lead successful lives as adults, according to research from Duke Medicine.

Reporting in the July 15 issue of JAMA Psychiatry, the Duke researchers found that children who had either a diagnosed psychiatric condition or a milder form that didn't meet the full diagnostic criteria were six times more likely than those who had no psychiatric issues to have difficulties in adulthood, including ...

Children with psychiatric problems were more likely to have health, legal, financial and social problems as adults even if their psychiatric disorders did not persist into adulthood and even if they did not meet the full diagnostic criteria for a disorder, according to an article published online by JAMA Psychiatry.

Neuropsychiatric disorders among young people ages 10 to 24 are a leading cause of disease burden globally. Unlike many chronic physical health problems, most psychiatric disorders are first diagnosed in childhood, which allows the disorder to affect a person's ...

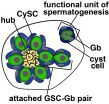

PHILADELPHIA - Stem cells are key for the continual renewal of tissues in our bodies. As such, manipulating stem cells also holds much promise for biomedicine if their regenerative capacity can be harnessed. However, understanding how stem cells govern normal tissue renewal is a field still in its infancy.

Researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania are making headway in this area by studying stem cells in their natural environment in an organism. Stem cell populations reside in areas called niches deep within different types of organs. ...

States with more restrictive alcohol policies and regulations have lower rates of self-reported drunk driving, according to a new study by researchers at the Boston University schools of public health and medicine and the University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

The research team assigned each state an "alcohol policy score," based on an aggregate of 29 alcohol policies, such as alcohol taxation and the use of sobriety checkpoints. Each 1 percentage point increase in the score was found to be associated with a 1 percent decrease in the likelihood of impaired driving, ...

Final results of the randomized intergroup EORTC, LYSA (Lymphoma Study Association), FIL (Fondazione Italiana Linfomi) H10 trial presented at the 13th International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma in Lugano, Switzerland, on 19 June 2015 show that early FDG-PET ( 2-deoxy-2[F-18]fluoro-D-glucose positron emission tomography) adapted treatment improves the outcome of early FDG-PET-positive patients with stages I/II Hodgkin lymphoma.

Dr. John Raemaekers of the Radboud University Medical Center Nijmegen and the Rijnstate Hospital Arnhem, The Netherlands, and EORTC principal ...

HOUSTON - (July 15, 2015) - Three-dimensional structures of boron nitride might be the right stuff to keep small electronics cool, according to scientists at Rice University.

Rice researchers Rouzbeh Shahsavari and Navid Sakhavand have completed the first theoretical analysis of how 3-D boron nitride might be used as a tunable material to control heat flow in such devices.

Their work appears this month in the American Chemical Society journal Applied Materials and Interfaces.

In its two-dimensional form, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN), aka white graphene, looks ...