Volcanic bacteria take minimalist approach to survival

2015-08-04

(Press-News.org) New research by scientists at New Zealand's University of Otago and GNS Science is helping to solve the puzzle of how bacteria are able to live in nutrient-starved environments. It is well-established that the majority of bacteria in soil ecosystems live in dormant states due to nutrient deprivation, but the metabolic strategies that enable their survival have not yet been shown.

The researchers took an extreme approach to resolving this enigma.

They studied a strain of acidobacteria named Pyrinomonas methylaliphatogenes that was cultivated from heated and acidic geothermal soils in New Zealand's Taup? Volcanic Zone. Remarkably, the bacterium was living in this inhospitable ecosystem despite its soil lacking the nutrients the microbe usually relied on.

Following in-depth studies on the genetic and biochemical capabilities of the organism, the authors uncovered that the bacterium actually took a highly minimalistic approach to survival. When its preferred carbohydrate nutrient sources are exhausted, it is able to scavenge trace amounts of the fuel hydrogen from the air. To survive, the organism simply requires atmospheric hydrogen and oxygen. It is 'living on thin air', so to speak.

The findings appear in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The paper co-authors include the Department of Microbiology and Immunology's Professor Greg Cook, his past PhD student Dr Chris Greening (now CSIRO) and GNS Science researchers Dr Matthew Stott and Dr Carlo Carere.

By focusing on a slow-growing isolate rather than a typical fast-growing lab strain, the team were able to get rich insight into the survival strategies of the 'dormant microbial majority'. Professor Cook says this is the first time that acidobacteria - the second most dominant bacteria in global soils - have been found to be able to consume hydrogen gas as an energy source. "Even though there are only low concentrations of the gas in the air, it still provides them with a constant and unlimited resource for survival," he says.

This publication is the latest in a trilogy of PNAS papers authored by Professor Cook and Dr Greening. Their other recent work showed that soil actinobacteria, another dominant phylum, demonstrate a similar metabolic flexibility in switching to scavenging hydrogen when starved of other nutrients.

In their latest paper, the researchers conclude by proposing that scavenging of trace gases such as hydrogen is an under-recognised general mechanism for bacterial survival and is likely to provide the energy to sustain a significant proportion of the bacterial communities in soils.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-08-04

A study including researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago found evidence that gut microbes affect circadian rhythms and metabolism in mice.

We know from studies on jet lag and night shifts that metabolism--how bodies use energy from food--is linked to the body's circadian rhythms. These rhythms, regular daily fluctuations in mental and bodily functions, are communicated and carried out via signals sent from the brain and liver. Light and dark signals guide circadian rhythms, but it appears that microbes ...

2015-08-04

The more than 200 species in the family Mormyridae communicate with one another in a way completely alien to our species: by means of electric discharges generated by an organ in their tails.

In a 2011 article in Science that described a group of mormyrids able to perceive subtle variations in the waveform of electric signals, Washington University in St. Louis biologist Bruce Carlson, PhD, noted that another group of mormyrids are much less discriminating (see illustration).

The fish with nuanced signal discrimination can glean a stunning amount of information from ...

2015-08-04

Cleaning up municipal and industrial wastewater can be dirty business, but engineers at the University of Colorado Boulder have developed an innovative wastewater treatment process that not only mitigates carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, but actively captures greenhouse gases as well.

The treatment method, known as Microbial Electrolytic Carbon Capture (MECC), purifies wastewater in an environmentally-friendly fashion by using an electrochemical reaction that absorbs more CO2 than it releases while creating renewable energy in the process.

"This energy-positive, carbon-negative ...

2015-08-04

(BOSTON) - Super productive factories of the future could employ fleets of genetically engineered bacterial cells, such as common E. coli, to produce valuable chemical commodities in an environmentally friendly way. By leveraging their natural metabolic processes, bacteria could be re-programmed to convert readily available sources of natural energy into pharmaceuticals, plastics and fuel products.

"The basic idea is that we want to accelerate evolution to make awesome amounts of valuable chemicals," said Wyss Core Faculty member George Church, Ph.D., who is a pioneer ...

2015-08-04

Some neutron stars may rival black holes in their ability to accelerate powerful jets of material to nearly the speed of light, astronomers using the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) have discovered.

"It's surprising, and it tells us that something we hadn't previously suspected must be going on in some systems that include a neutron star and a more-normal companion star," said Adam Deller, of ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy.

Black holes and neutron stars are respectively the densest and second most dense forms of matter known in the Universe. ...

2015-08-04

From an early age, human infants are able to produce vocalisations in a wide range of emotional states and situations - an ability felt to be one of the factors required for the development of language. Researchers have found that wild bonobos (our closest living relatives) are able to vocalize in a similar manner. Their findings challenge how we think about the evolution of communication and potentially move the dividing line between humans and other apes.

Animal vocalisations are usually made in relatively narrow behavioural contexts linked to emotional states, such ...

2015-08-04

Washington, DC-- Climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions will alter the way that Americans heat and cool their homes. By the end of this century, the number of days each year that heating and air conditioning are used will decrease in the Northern states, as winters get warmer, and increase in Southern states, as summers get hotter, according to a new study from a high school student, Yana Petri, working with Carnegie's Ken Caldeira. It is published by Scientific Reports.

"Changes in outdoor temperatures have a substantial impact on energy use inside," Caldeira ...

2015-08-04

A team of scientists believe they have shown that memories are more robust than we thought and have identified the process in the brain, which could help rescue lost memories or bury bad memories, and pave the way for new drugs and treatment for people with memory problems.

Published in the journal Nature Communications a team of scientists from Cardiff University found that reminders could reverse the amnesia caused by methods previously thought to produce total memory loss in rats. .

"Previous research in this area found that when you recall a memory it is sensitive ...

2015-08-04

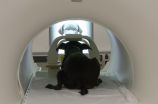

Dogs have a specialized region in their brains for processing faces, a new study finds. PeerJ is publishing the research, which provides the first evidence for a face-selective region in the temporal cortex of dogs.

"Our findings show that dogs have an innate way to process faces in their brains, a quality that has previously only been well-documented in humans and other primates," says Gregory Berns, a neuroscientist at Emory University and the senior author of the study.

Having neural machinery dedicated to face processing suggests that this ability is hard-wired ...

2015-08-04

Trauma may cause distinct and long-lasting effects even in people who do not develop PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), according to research by scientists working at the University of Oxford's Department of Psychiatry. It is already known that stress affects brain function and may lead to PTSD, but until now the underlying brain networks have proven elusive.

Led by Prof Morten Kringelbach, the Oxford team's systematic meta-analysis of all brain research on PTSD is published in the journal Neuroscience and Biobehavioural Reviews. The research is part of a larger ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Volcanic bacteria take minimalist approach to survival