Protecting the environment by re-thinking death

2015-08-04

(Press-News.org) Scientists first had to re-think death before they could develop a way of testing the potential harm to the environment caused by thousands of chemicals humankind uses each day.

Researchers led by Dr Roman Ashauer, of the Environment Department at the University of York, refined the technique of survival analysis used routinely by toxicologists, biologists, medical researchers and engineers. The research could pave the way for testing the estimated 15,000 substances discovered daily.

Survival analysis which helps to predict a huge range of functions such as the survival of patients after medical treatment and the endurance of engine components, is based on a consideration of death either as a random event or triggered when a threshold of stress is passed. In the latter case, an individual, or an engine part, is more likely to survive repeated episodes of toxicity or stress.

The research team included scientists from the Department of Environmental Toxicology in the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research in Leipzig and the Environmental Toxicology Center for Applied Geosciences at Eberhard Karls University, Tubingen.

They used ecotoxicology -- the effect of toxic chemicals on biological organisms -- as an example to demonstrate the impact of their proposed new model of survival. By considering death as a continuum between a random event and individual tolerance, they studied processes such as toxicity and organism recovery.

The research, which is published in Environmental Science & Technology, showed that causes of death lie between the two extremes and are related to chemical class and mechanism of toxicity. In previous research, the scientists developed theoretical mathematical equations for the two assumptions but the new study is the first time they have been used on real data.

By using these computational tools, scientists could in theory analyse every chemical known to man using high throughput screening. Those whose chemical structures are found to potentially affect organisms and be harmful to the environment could be subject to further more rigorous testing.

Dr Ashauer said: "We advance the understanding and prediction of toxicity caused by chemicals, by re-thinking death. Our innovative approach to death can help translate in vitro test results into predictions of toxic effects on organisms and improve testing regimes for new chemicals.

"We are convinced that our work will also facilitate important new insights in other fields of science and engineering."

INFORMATION:

The Swiss National Science Foundation and the Swiss Federal Office for the Environment funded the research.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-08-04

New research by scientists at New Zealand's University of Otago and GNS Science is helping to solve the puzzle of how bacteria are able to live in nutrient-starved environments. It is well-established that the majority of bacteria in soil ecosystems live in dormant states due to nutrient deprivation, but the metabolic strategies that enable their survival have not yet been shown.

The researchers took an extreme approach to resolving this enigma.

They studied a strain of acidobacteria named Pyrinomonas methylaliphatogenes that was cultivated from heated and acidic geothermal ...

2015-08-04

A study including researchers from the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago found evidence that gut microbes affect circadian rhythms and metabolism in mice.

We know from studies on jet lag and night shifts that metabolism--how bodies use energy from food--is linked to the body's circadian rhythms. These rhythms, regular daily fluctuations in mental and bodily functions, are communicated and carried out via signals sent from the brain and liver. Light and dark signals guide circadian rhythms, but it appears that microbes ...

2015-08-04

The more than 200 species in the family Mormyridae communicate with one another in a way completely alien to our species: by means of electric discharges generated by an organ in their tails.

In a 2011 article in Science that described a group of mormyrids able to perceive subtle variations in the waveform of electric signals, Washington University in St. Louis biologist Bruce Carlson, PhD, noted that another group of mormyrids are much less discriminating (see illustration).

The fish with nuanced signal discrimination can glean a stunning amount of information from ...

2015-08-04

Cleaning up municipal and industrial wastewater can be dirty business, but engineers at the University of Colorado Boulder have developed an innovative wastewater treatment process that not only mitigates carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, but actively captures greenhouse gases as well.

The treatment method, known as Microbial Electrolytic Carbon Capture (MECC), purifies wastewater in an environmentally-friendly fashion by using an electrochemical reaction that absorbs more CO2 than it releases while creating renewable energy in the process.

"This energy-positive, carbon-negative ...

2015-08-04

(BOSTON) - Super productive factories of the future could employ fleets of genetically engineered bacterial cells, such as common E. coli, to produce valuable chemical commodities in an environmentally friendly way. By leveraging their natural metabolic processes, bacteria could be re-programmed to convert readily available sources of natural energy into pharmaceuticals, plastics and fuel products.

"The basic idea is that we want to accelerate evolution to make awesome amounts of valuable chemicals," said Wyss Core Faculty member George Church, Ph.D., who is a pioneer ...

2015-08-04

Some neutron stars may rival black holes in their ability to accelerate powerful jets of material to nearly the speed of light, astronomers using the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) have discovered.

"It's surprising, and it tells us that something we hadn't previously suspected must be going on in some systems that include a neutron star and a more-normal companion star," said Adam Deller, of ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy.

Black holes and neutron stars are respectively the densest and second most dense forms of matter known in the Universe. ...

2015-08-04

From an early age, human infants are able to produce vocalisations in a wide range of emotional states and situations - an ability felt to be one of the factors required for the development of language. Researchers have found that wild bonobos (our closest living relatives) are able to vocalize in a similar manner. Their findings challenge how we think about the evolution of communication and potentially move the dividing line between humans and other apes.

Animal vocalisations are usually made in relatively narrow behavioural contexts linked to emotional states, such ...

2015-08-04

Washington, DC-- Climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions will alter the way that Americans heat and cool their homes. By the end of this century, the number of days each year that heating and air conditioning are used will decrease in the Northern states, as winters get warmer, and increase in Southern states, as summers get hotter, according to a new study from a high school student, Yana Petri, working with Carnegie's Ken Caldeira. It is published by Scientific Reports.

"Changes in outdoor temperatures have a substantial impact on energy use inside," Caldeira ...

2015-08-04

A team of scientists believe they have shown that memories are more robust than we thought and have identified the process in the brain, which could help rescue lost memories or bury bad memories, and pave the way for new drugs and treatment for people with memory problems.

Published in the journal Nature Communications a team of scientists from Cardiff University found that reminders could reverse the amnesia caused by methods previously thought to produce total memory loss in rats. .

"Previous research in this area found that when you recall a memory it is sensitive ...

2015-08-04

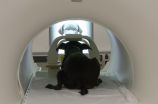

Dogs have a specialized region in their brains for processing faces, a new study finds. PeerJ is publishing the research, which provides the first evidence for a face-selective region in the temporal cortex of dogs.

"Our findings show that dogs have an innate way to process faces in their brains, a quality that has previously only been well-documented in humans and other primates," says Gregory Berns, a neuroscientist at Emory University and the senior author of the study.

Having neural machinery dedicated to face processing suggests that this ability is hard-wired ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Protecting the environment by re-thinking death