"At first when I saw the news trickling in from Kathmandu, I thought there was a problem of communication, that we weren't hearing the full extent of the damage," says Avouac, Caltech's Earle C. Anthony Professor of Geology. "As it turns out, there was little damage to the regular dwellings, and thankfully, as a result, there were far fewer deaths than I originally anticipated."

Using data from the GPS stations, an accelerometer that measures ground motion in Kathmandu, data from seismological stations around the world, and radar images collected by orbiting satellites, an international team of scientists led by Caltech has pieced together the first complete account of what physically happened during the Gorkha earthquake--a picture that explains how the large earthquake wound up leaving the majority of low-story buildings unscathed while devastating some treasured taller structures.

The findings are described in two papers that now appear online. The first, in the journal Nature Geoscience, is based on an analysis of seismological records collected more than 1,000 kilometers from the epicenter and places the event in the context of what scientists knew of the seismic setting near Gorkha before the earthquake. The second paper, appearing in Science Express, goes into finer detail about the rupture process during the April 25 earthquake and how it shook the ground in Kathmandu.

In the first study, the researchers show that the earthquake occurred on the Main Himalayan Thrust (MHT), the main megathrust fault along which northern India is pushing beneath Eurasia at a rate of about two centimeters per year, driving the Himalayas upward. Based on GPS measurements, scientists know that a large portion of this fault is "locked." Large earthquakes typically release stress on such locked faults--as the lower tectonic plate (here, the Indian plate) pulls the upper plate (here, the Eurasian plate) downward, strain builds in these locked sections until the upper plate breaks free, releasing strain and producing an earthquake. There are areas along the fault in western Nepal that are known to be locked and have not experienced a major earthquake since a big one (larger than magnitude 8.5) in 1505. But the Gorkha earthquake ruptured only a small fraction of the locked zone, so there is still the potential for the locked portion to produce a large earthquake.

"The Gorkha earthquake didn't do the job of transferring deformation all the way to the front of the Himalaya," says Avouac. "So the Himalaya could certainly generate larger earthquakes in the future, but we have no idea when."

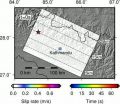

The epicenter of the April 25 event was located in the Gorkha District of Nepal, 75 kilometers to the west-northwest of Kathmandu, and propagated eastward at a rate of about 2.8 kilometers per second, causing slip in the north-south direction--a progression that the researchers describe as "unzipping" a section of the locked fault.

"With the geological context in Nepal, this is a place where we expect big earthquakes. We also knew, based on GPS measurements of the way the plates have moved over the last two decades, how 'stuck' this particular fault was, so this earthquake was not a surprise," says Jean Paul Ampuero, assistant professor of seismology at Caltech and coauthor on the Nature Geoscience paper. "But with every earthquake there are always surprises."

In this case, one of the surprises was that the quake did not rupture all the way to the surface. Records of past earthquakes on the same fault--including a powerful one (possibly as strong as magnitude 8.4) that shook Kathmandu in 1934--indicate that ruptures have previously reached the surface. But Avouac, Ampuero, and their colleagues used satellite Synthetic Aperture Radar data and a technique called back projection that takes advantage of the dense arrays of seismic stations in the United States, Europe, and Australia to track the progression of the earthquake, and found that it was quite contained at depth. The high-frequency waves that were largely produced in the lower section of the rupture occurred at a depth of about 15 kilometers.

"That was good news for Kathmandu," says Ampuero. "If the earthquake had broken all the way to the surface, it could have been much, much worse."

The researchers note, however, that the Gorkha earthquake did increase the stress on the adjacent portion of the fault that remains locked, closer to Kathmandu. It is unclear whether this additional stress will eventually trigger another earthquake or if that portion of the fault will "creep," a process that allows the two plates to move slowly past one another, dissipating stress. The researchers are building computer models and monitoring post-earthquake deformation of the crust to try to determine which scenario is more likely.

Another surprise from the earthquake, one that explains why many of the homes and other buildings in Kathmandu were spared, is described in the Science Express paper. Avouac and his colleagues found that for such a large-magnitude earthquake, high-frequency shaking in Kathmandu was actually relatively mild. And it is high-frequency waves, with short periods of vibration of less than one second, that tend to affect low-story buildings. The Nature Geoscience paper showed that the high-frequency waves that the quake produced came from the deeper edge of the rupture, on the northern end away from Kathmandu.

The GPS records described in the Science Express paper show that within the zone that experienced the greatest amount of slip during the earthquake--a region south of the sources of high-frequency waves and closer to Kathmandu--the onset of slip on the fault was actually very smooth. It took nearly two seconds for the slip rate to reach its maximum value of one meter per second. In general, the more abrupt the onset of slip during an earthquake, the more energetic the radiated high-frequency seismic waves. So the relatively gradual onset of slip in the Gorkha event explains why this patch, which experienced a large amount of slip, did not generate many high-frequency waves.

"It would be good news if the smooth onset of slip, and hence the limited induced shaking, were a systematic property of the Himalayan megathrust fault, or of megathrust faults in general." says Avouac. "Based on observations from this and other megathrust earthquakes, this is a possibility."

In contrast to what they saw with high-frequency waves, the researchers found that the earthquake produced an unexpectedly large amount of low-frequency waves with longer periods of about five seconds. This longer-period shaking was responsible for the collapse of taller structures in Kathmandu, such as the Dharahara Tower, a 60-meter-high tower that survived larger earthquakes in 1833 and 1934 but collapsed completely during the Gorkha quake.

To understand this, consider plucking the strings of a guitar. Each string resonates at a certain natural frequency, or pitch, depending on the length, composition, and tension of the string. Likewise, buildings and other structures have a natural pitch or frequency of shaking at which they resonate; in general, the taller the building, the longer the period at which it resonates. If a strong earthquake causes the ground to shake with a frequency that matches a building's pitch, the shaking will be amplified within the building, and the structure will likely collapse.

Turning to the GPS records from two of Avouac's stations in the Kathmandu Valley, the researchers found that the effect of the low-frequency waves was amplified by the geological context of the Kathmandu basin. The basin is an ancient lakebed that is now filled with relatively soft sediment. For about 40 seconds after the earthquake, seismic waves from the quake were trapped within the basin and continued to reverberate, ringing like a bell with a frequency of five seconds.

"That's just the right frequency to damage tall buildings like the Dharahara Tower because it's close to their natural period," Avouac explains.

In follow-up work, Domniki Asimaki, professor of mechanical and civil engineering at Caltech, is examining the details of the shaking experienced throughout the basin. On a recent trip to Kathmandu, she documented very little damage to low-story buildings throughout much of the city but identified a pattern of intense shaking experienced at the edges of the basin, on hilltops or in the foothills where sediment meets the mountains. This was largely due to the resonance of seismic waves within the basin.

Asimaki notes that Los Angeles is also built atop sedimentary deposits and is surrounded by hills and mountain ranges that would also be prone to this type of increased shaking intensity during a major earthquake.

"In fact," she says, "the buildings in downtown Los Angeles are much taller than those in Kathmandu and therefore resonate with a much lower frequency. So if the same shaking had happened in L.A., a lot of the really tall buildings would have been challenged."

That points to one of the reasons it is important to understand how the land responded to the Gorkha earthquake, Avouac says. "Such studies of the site effects in Nepal provide an important opportunity to validate the codes and methods we use to predict the kind of shaking and damage that would be expected as a result of earthquakes elsewhere, such as in the Los Angeles Basin."

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on the Nature Geoscience paper, "Unzipping lower edge of locked Main Himalayan Thrust during the 2015, Mw 7.8 Gorkha earthquake, Nepal," are Lingsen Meng (PhD '12) of UC Los Angeles, Shengji Wei of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, and Teng Wang of Southern Methodist University. The lead author on the Science paper, "Slip pulse and resonance of Kathmandu basin during the 2015 Mw 7.8 Gorkha earthquake, Nepal imaged with geodesy" is John Galetzka, formerly an associate staff geodesist at Caltech and now a project manager at UNAVCO in Boulder, Colorado. Caltech research geodesist Joachim Genrich is also a coauthor, as are Susan Owen and Angelyn Moore of JPL. For a full list of authors, please see the paper.

The Nepal Geodetic Array was funded by Caltech, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the National Science Foundation. Additional funding for the Science study came from the Department of Foreign International Development (UK), the Royal Society (UK), the United Nations Development Programme, and the Nepal Academy for Science and Technology, as well as NASA and the Department of Foreign International Development.