Linking cell-population to whole-fish growth

2015-08-07

(Press-News.org) This news release is available in French and German.

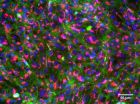

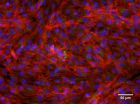

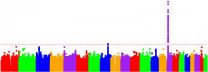

Every year, more than a million fish are used for toxicity testing and scientific research in the EU alone, and around 400 fish are needed for a single fish early-life stage test. Such toxicity tests are often required by regulatory authorities for new chemical substances, as fish are particularly sensitive to contaminants in water at early developmental stages. However, the increasing use of experimental animals is ethically questionable. In addition, conventional tests are complex, expensive and take weeks or months to complete. Alternative approaches are therefore being sought by scientists, regulators and industry. A promising new method has now been demonstrated by an Eawag study, conducted in collaboration with the ETH, the EPFL and the University of York (UK). The results have been published in the journal Science Advances : rather than using live fish (in vivo), the tests are performed with fish cells (in vitro). After just five days, cell-population growth, inhibited to a greater or lesser extent under chemical stress - combined with modelling of toxicological effects - shows excellent agreement with data from independently conducted in vivo experiments.

Environmental toxicologist Professor Kristin Schirmer, who is leading Eawag's efforts to reduce the use of experimental animals, comments: "This is a major step towards simpler, less expensive and more rapid toxicity testing for the authorisation and use of new chemicals. It's the first time we've been able to use cell cultures to accurately predict chemical effects on growth which would only emerge after weeks or even months in live fish." The mechanism underlying the new method appears simple: the pesticides used in the study inhibit fish growth - the higher the concentrations to which the animals are exposed, the more their growth is reduced. The same effects were shown for the gill cell populations cultured in the laboratory. Kristin Schirmer explains: "The reason why the results can be extrapolated so well is that bigger fish don't have bigger cells, but more cells, and we calculate the concentration of the substance in the cells." The model thus predicts what happens if the fish is exposed to the test substance in water - which in turn can help to refine other tests and predictive models.

The new approach is not, however, as simple as it initially appears. To determine what concentrations in cultured cells have the same effects as in live fish requires elaborate modelling and a detailed knowledge of substance properties. In addition, it is not clear whether gill cells will prove to be representative for all types of fish tissue. Other cells may react differently, and other substances may be biotransformed. Nonetheless, the study is of considerable interest for experts because of the novel approach pursued. Dr Roman Ashauer, who initiated the study and is now working at the University of York, says: "The traditional work flow for chemical risk assessment has been 'test first, interpret later'. We've taken a different approach, by first modifying a relatively simple mathematical model of fish growth and then feeding the necessary experimental data into this model." The authors hope that this approach will be taken up by other scientists to test its wider applicability, and the initial signs are encouraging: at a Annual Meeting of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC Europe) held in Glasgow, Dr Julita Stadnicka-Michalak, the study's first author, received the prestigious Young Scientist Award.

INFORMATION:

Original paper:

Toxicology across scales: cell population growth in vitro predicts reduced fish growth; Julita Stadnicka Michalak, Kristin Schirmer, Roman Ashauer (2015); Science Advances. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1500302

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2015-08-07

Coral Gables, FL (August 7, 2015)--Two new studies show that the tone of a candidate's voice can influence whether he or she wins office.

"Our analyses of both real-life elections and data from experiments show that candidates with lower-pitched voices are generally more successful at the polls," explains Casey Klofstad, associate professor of political science at the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences, who is corresponding author on both studies.

The first study, published online in Political Psychology, shows that candidates who ran in the 2012 U.S. ...

2015-08-07

CRG researchers have proposed a new theory to explain the origin of whole genome duplication at the beginning of the yeast lineage. Yeasts are single-celled fungi that originated over 100 million years ago. The ability of these organisms to ferment carbohydrates is widely used for food and drink fermentation. Yeasts are also one of the most commonly used model organisms in research. For example, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is used to make bread, wine and beer, was the first eukaryotic organism to be sequenced (in 1996) and is a key model organism for studying ...

2015-08-07

Medulloblastoma, the most commonly occurring malignant brain tumor in children, can be classified into four subgroups--each with a different risk profile requiring subgroup-specific therapy. Currently, subgroup determination is done after surgical removal of the tumor. Investigators at Children's Hospital Los Angeles have now discovered that these subgroups can be determined non-invasively, using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). The paper will be published online by the journal Neuro-Oncology (Oxford Press) on August 7.

"By identification of the tumor subgroup ...

2015-08-07

TORONTO - Hearing loss in adults is under treated despite evidence that hearing aid technology can significantly lessen depression and anxiety and improve cognitive functioning, according to a presentation at the American Psychological Association's 123rd Annual Convention.

"Many hard of hearing people battle silently with their invisible hearing difficulties, straining to stay connected to the world around them, reluctant to seek help," said David Myers, PhD, a psychology professor and textbook writer at Hope College in Michigan who lives with hearing loss.

In a ...

2015-08-07

Philadelphia - A large randomized clinical trial of an emergency department (ED)-based program aimed at reducing incidents of excessive drinking and partner violence in women did not result in significant improvements in either risk factor, according to a new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Contrary to previous studies which found brief interventions in the ED setting to be effective for reducing alcohol consumption to safe levels and preventing subsequent injury among patients with hazardous drinking, the new ...

2015-08-07

Capture and convert--this is the motto of carbon dioxide reduction, a process that stops the greenhouse gas before it escapes from chimneys and power plants into the atmosphere and instead turns it into a useful product.

One possible end product is methanol, a liquid fuel and the focus of a recent study conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory. The chemical reactions that make methanol from carbon dioxide rely on a catalyst to speed up the conversion, and Argonne scientists identified a new material that could fill this role. With ...

2015-08-07

For years chemotherapy has been one of most common methods of treating cancer, but it comes with the substantial drawback of effecting healthy cells in the same way that it effects cancerous cells. This means that a subject of chemotherapy can experience great pain and sickness as a side effect of the potentially lifesaving treatment. A solution to this problem is targeted therapy, or the use of drugs, which more specifically targets cancer cells while ignoring nearby healthy cells. Targeted therapy is dependent on drugs which are tailored to inhibited cancer cell growth, ...

2015-08-07

A new test developed by UBC researchers allows physicians to measure the effects of gene silencing therapy in Huntington's disease and will support the first human clinical trial of a drug that targets the genetic cause of the disease.

The gene silencing therapy being tested by UBC researchers aims to reduce the levels of a toxic protein in the brain that causes Huntington's disease.

The test was developed by Amber Southwell, Michael Hayden, and Blair Leavitt of UBC's Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics and the Centre for Huntington Disease in collaboration ...

2015-08-07

This news release is available in Japanese.

There are no magic bullets for global energy needs. But fuel cells in which electrical energy is harnessed directly from live, self-sustaining chemical reactions promise cheaper alternatives to fossil fuels.

To facilitate faster energy conversion in these cells, scientists disperse nanoparticles made from special metals called 'noble' metals, for example gold, silver and platinum along the surface of an electrode. These metals are not as chemically responsive as other metals at the macroscale but their atoms become more ...

2015-08-07

Scientists searched the chromosomes of more than 4,000 Huntington's disease patients and found that DNA repair genes may determine when the neurological symptoms begin. Partially funded by the National Institutes of Health, the results may provide a guide for discovering new treatments for Huntington's disease and a roadmap for studying other neurological disorders.

"Our hope is to find ways that we can slow or delay the onset of Huntington's devastating symptoms," said James Gusella, Ph.D., director of the Center for Human Genetic Research at Massachusetts General ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Linking cell-population to whole-fish growth