(Press-News.org) CRG researchers have proposed a new theory to explain the origin of whole genome duplication at the beginning of the yeast lineage. Yeasts are single-celled fungi that originated over 100 million years ago. The ability of these organisms to ferment carbohydrates is widely used for food and drink fermentation. Yeasts are also one of the most commonly used model organisms in research. For example, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is used to make bread, wine and beer, was the first eukaryotic organism to be sequenced (in 1996) and is a key model organism for studying molecular and cellular biology.

Once the yeast genome sequences were available, researchers were able to determine that the yeast genome contains more than 50 repeated fragments. Since then, the scientific community has accepted the theory that yeast underwent a whole genome duplication, a phenomenon that is not isolated and can also be found in other species. For instance, we know that whole genome duplications were important in the early evolution of vertebrates and that it is a very common phenomenon in plants, especially cultivated ones.

The CRG scientists Marina Marcet-Houben and Toni Gabaldón (CRG group leader and ICREA Research Professor) have now studied the origins of the whole genome duplication in yeast to gain a more thorough understanding of this phenomenon, which is thought to have played a key role the evolution and adaption of the species. Their results were published today in the journal PLoS Biology. Unexpectedly, they show that the appearance of duplicated genes was not caused by a simple duplication of the whole genome but rather by a hybridization of two different species. Their proposal, which is at odds with the currently most widely accepted theory in the scientific community, provides new insight into this key process during genome evolution and the origins of species.

"When we first saw the results of our study, we thought there had been some kind of mistake. Honestly, when the results are not what you expect and contradict what is established, the first thing you do is think that they were affected by some kind of problem. But once all the potential problems have been discarded, you begin to interpret the data objectively, without preconceived ideas, and to do real science. That's when we started to consider the different possible explanations and to work on a new idea," explained Toni Gabaldón, the lead investigator of the study and head of the Comparative Genomics Group. He added, "It's one of those magical moments of research when, once you open your mind enough, you can surrender to the evidence in the data and discard what you had considered as a proven fact to adopt an entirely new paradigm, no matter how implausible it seems at first. Afterwards you reel in your new paradigm and see that it also explains other independent observations. Scientifically it has been a challenging and rewarding experience. "

Looking at the past to understand the present and predict the future

Once genomics entered into evolutionary studies, scientists were able to show that the phenomenon of whole genome duplication is common to several species, which leads us to believe that it is one of the key mechanisms in the evolution and adaptability of species. Duplicating the genome would give an organism multiple copies of genes, so that it could vary some of these copies over time without loosing the original and thus produce new proteins with novel functions, which could give it an evolutionary advantage by permitting it to adapt more readily and to cope with different conditions.

However, it would seem intuitively to make sense that incorporating something different through hybridization, rather than duplicating what is already present, would lead more rapidly to a higher degree of diversity and to better adaptation. The problems with this are that most hybrid crosses are not viable, and if viable, the resulting hybrids are sterile and therefore unable to pass on their new genetic information to their offspring. Because of this, and because of the similarities of the repeated genes, the idea of duplicating the whole genome previously seemed more plausible.

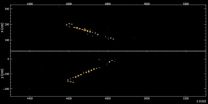

The work of Marcet-Houben and Gabaldón has now revealed that, for yeast, hybridization was indeed behind the duplication of some genes. The researchers analyzed genomic data with computational tool, based on cutting-edge computational methods, and designed by the Gabaldón group, to study the phylogenetic trees of yeast families. This tool allowed the researchers to reconstruct gene duplications and to determine what happened in evolutionary time, making it a computational equivalent of carbon-14 dating for fossils. To their surprise, they found that the age of some duplicated genes seemed to be much greater than that predicted by the theory of whole genome duplication. Rather than supporting a genome duplication event at the time when yeast evolved to have twice the number of chromosomes, their data indicated that the duplicated genes had begun to diverge long before. This result suggested the possibility of hybridization between species. In this case, the genes that have been duplicated still differ from each other, so that their divergence preceded the duplication of the chromosome.

The hybridization hypothesis has strong implications on how we interpret the origin and evolution of duplicated genomes. For instance, we no longer need to imagine that massive and rapid changes are necessary to generate new functions from duplicated genome regions, since hybridization combines the properties of the two parental lines from day one and opens the door to new ecological and evolutionary opportunities.

The new proposal is strengthened when we see that the number of genome duplications is much higher in cultivated plants. "We should consider whether genome duplications in other species also hide hybridizations since, for example, it seems clear that we could be facing a similar situation in cultivated plants. Traditionally, growing a plant and improving its production will lead to forced hybridizations" commented Gabaldón.

Being able to "look" at 100 million-year-old eukaryotic genomes will now allow us to deepen our knowledge about genomes as well as about the evolutionary mechanisms that lead to diversifying and acquiring new function. This challenging and innovative work will have major implications on how we interpret the functional and evolutionary consequences of genome duplication. It also highlights the importance of basic research for understanding genomes, evolution and diversity.

INFORMATION:

Medulloblastoma, the most commonly occurring malignant brain tumor in children, can be classified into four subgroups--each with a different risk profile requiring subgroup-specific therapy. Currently, subgroup determination is done after surgical removal of the tumor. Investigators at Children's Hospital Los Angeles have now discovered that these subgroups can be determined non-invasively, using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). The paper will be published online by the journal Neuro-Oncology (Oxford Press) on August 7.

"By identification of the tumor subgroup ...

TORONTO - Hearing loss in adults is under treated despite evidence that hearing aid technology can significantly lessen depression and anxiety and improve cognitive functioning, according to a presentation at the American Psychological Association's 123rd Annual Convention.

"Many hard of hearing people battle silently with their invisible hearing difficulties, straining to stay connected to the world around them, reluctant to seek help," said David Myers, PhD, a psychology professor and textbook writer at Hope College in Michigan who lives with hearing loss.

In a ...

Philadelphia - A large randomized clinical trial of an emergency department (ED)-based program aimed at reducing incidents of excessive drinking and partner violence in women did not result in significant improvements in either risk factor, according to a new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Contrary to previous studies which found brief interventions in the ED setting to be effective for reducing alcohol consumption to safe levels and preventing subsequent injury among patients with hazardous drinking, the new ...

Capture and convert--this is the motto of carbon dioxide reduction, a process that stops the greenhouse gas before it escapes from chimneys and power plants into the atmosphere and instead turns it into a useful product.

One possible end product is methanol, a liquid fuel and the focus of a recent study conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory. The chemical reactions that make methanol from carbon dioxide rely on a catalyst to speed up the conversion, and Argonne scientists identified a new material that could fill this role. With ...

For years chemotherapy has been one of most common methods of treating cancer, but it comes with the substantial drawback of effecting healthy cells in the same way that it effects cancerous cells. This means that a subject of chemotherapy can experience great pain and sickness as a side effect of the potentially lifesaving treatment. A solution to this problem is targeted therapy, or the use of drugs, which more specifically targets cancer cells while ignoring nearby healthy cells. Targeted therapy is dependent on drugs which are tailored to inhibited cancer cell growth, ...

A new test developed by UBC researchers allows physicians to measure the effects of gene silencing therapy in Huntington's disease and will support the first human clinical trial of a drug that targets the genetic cause of the disease.

The gene silencing therapy being tested by UBC researchers aims to reduce the levels of a toxic protein in the brain that causes Huntington's disease.

The test was developed by Amber Southwell, Michael Hayden, and Blair Leavitt of UBC's Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics and the Centre for Huntington Disease in collaboration ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

There are no magic bullets for global energy needs. But fuel cells in which electrical energy is harnessed directly from live, self-sustaining chemical reactions promise cheaper alternatives to fossil fuels.

To facilitate faster energy conversion in these cells, scientists disperse nanoparticles made from special metals called 'noble' metals, for example gold, silver and platinum along the surface of an electrode. These metals are not as chemically responsive as other metals at the macroscale but their atoms become more ...

Scientists searched the chromosomes of more than 4,000 Huntington's disease patients and found that DNA repair genes may determine when the neurological symptoms begin. Partially funded by the National Institutes of Health, the results may provide a guide for discovering new treatments for Huntington's disease and a roadmap for studying other neurological disorders.

"Our hope is to find ways that we can slow or delay the onset of Huntington's devastating symptoms," said James Gusella, Ph.D., director of the Center for Human Genetic Research at Massachusetts General ...

Scientists on the NOvA experiment saw their first evidence of oscillating neutrinos, confirming that the extraordinary detector built for the project not only functions as planned but is also making great progress toward its goal of a major leap in our understanding of these ghostly particles.

NOvA is on a quest to learn more about the abundant yet mysterious particles called neutrinos, which flit through ordinary matter as though it weren't there. The first NOvA results, released this week at the American Physical Society's Division of Particles and Fields conference ...

WORCESTER, MA -- Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School have found that Google Glass, a head-mounted streaming audio/video device, may be used to effectively extend bed-side toxicology consults to distant health care facilities such as community and rural hospitals to diagnose and manage poisoned patients. Published in the Journal of Medical Toxicology, the study also showed preliminary data that suggests the hands-free device helps physicians in diagnosing specific poisonings and can enhance patient care.

"In the present era of value-based care, ...