(Press-News.org) Athens, Ga. - Recent research published in the journal Microsystems & Nanoengineering could eventually change the way people living with prosthetics and spinal cord injury lead their lives.

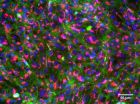

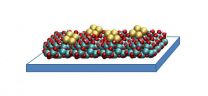

Instead of using neural prosthetic devices--which suffer from immune-system rejection and are believed to fail due to a material and mechanical mismatch--a multi-institutional team, including Lohitash Karumbaiah of the University of Georgia's Regenerative Bioscience Center, has developed a brain-friendly extracellular matrix environment of neuronal cells that contain very little foreign material. These by-design electrodes are shielded by a covering that the brain recognizes as part of its own composition.

Although once believed to be devoid of immune cells and therefore of immune responses, the brain is now recognized to have its own immune system that protects it against foreign invaders.

"This is not by any means the device that you're going to implant into a patient," said Karumbaiah, an assistant professor of animal and dairy science in the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. "This is proof of concept that extracellular matrix can be used to ensheathe a functioning electrode without the use of any other foreign or synthetic materials."

Implantable neural prosthetic devices in the brain have been around for almost two decades, helping people living with limb loss and spinal cord injury become more independent. However, not only do neural prosthetic devices suffer from immune-system rejection, but most are believed to eventually fail because of a mismatch between the soft brain tissue and the rigid devices.

The collaboration, led by Wen Shen and Mark Allen of the University of Pennsylvania, found that the extracellular matrix derived electrodes adapted to the mechanical properties of brain tissue and were capable of acquiring neural recordings from the brain cortex.

"Neural interface technology is literally mind boggling, considering that one might someday control a prosthetic limb with one's own thoughts," Karumbaiah said.

The study's joint collaborators were Ravi Bellamkonda, who conceived the new approach and is chair of the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, as well as Allen, who at the time was director of the Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology.

"Hopefully, once we converge upon the nanofabrication techniques that would enable these to be clinically translational, this same methodology could then be applied in getting these extracellular matrix derived electrodes to be the next wave of brain implants," Karumbaiah said.

Currently, one out of every 190 Americans is living with limb loss, according to the National Institutes of Health. There is a significant burden in cost of care and quality of life for people suffering from this disability.

The research team is one part of many in the prosthesis industry, which includes those who design the robotics for the artificial limbs, others who make the neural prosthetic devices and developers who design the software that decodes the neural signal.

"What neural prosthetic devices do is communicate seamlessly to an external prosthesis," Karumbaiah said, "providing independence of function without having to have a person or a facility dedicated to their care."

Karumbaiah hopes further collaboration will allow them to make positive changes in the industry, saying that, "it's the researcher-to-industry kind of conversation that now needs to take place, where companies need to come in and ask: 'What have you learned? How are the devices deficient, and how can we make them better?'"

INFORMATION:

The study, "Extracellular matrix-based intracortical microelectrodes: Toward a microfabricated neural interface based on natural materials," is available at http://www.nature.com/articles/micronano201510.

Regenerative Bioscience Center

The Regenerative Bioscience Center at the University of Georgia links researchers and resources collaborating in a wide range of disciplines to develop new cures for the devastating diseases. With its potential restorative powers, regenerative medicine could offer new ways of treating diseases for which there are currently no treatments--including heart disease, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and stroke. The RBC is a collaboration geared toward identifying regenerative solutions for numerous medical conditions that affect both animals and people. For more information, see http://www.rbc.uga.edu.

When the right gene is expressed in the right manner in the right population of stem cells, the developing mouse brain can exhibit primate-like features. In a paper publishing August 7th in the Open Access journal PLOS Biology, researchers at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) succeeded in mimicking the sustained expression of the transcription factor Pax6 as seen in the developing human brain, in mouse cortical progenitor cells. This altered the behavior of these cells to one that is akin to that of progenitors in the developing primate ...

The common baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is used to make bread, wine and beer, and is the laboratory workhorse for a substantial proportion of research into molecular and cell biology. It was also the first non-bacterial living thing to have its genome sequenced, back in 1996. However, when the sequence of that genome emerged it appeared that the scientists were seeing double - the organism seemed to have two very different versions of many of its genes. How could this have happened?

Researchers from the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) Barcelona, Spain, ...

Berkeley -- While the eyes may be a window into one's soul, new research led by scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that the pupils could also reveal whether one is a hunter or hunted.

An analysis of 214 species of land animals shows that a creature's ecological niche is a strong predictor of pupil shape. Species with pupils that are vertical slits are more likely to be ambush predators that are active both day and night. In contrast, those with horizontally elongated pupils are extremely likely to be plant-eating prey species with eyes on ...

This news release is available in French and German.

Every year, more than a million fish are used for toxicity testing and scientific research in the EU alone, and around 400 fish are needed for a single fish early-life stage test. Such toxicity tests are often required by regulatory authorities for new chemical substances, as fish are particularly sensitive to contaminants in water at early developmental stages. However, the increasing use of experimental animals is ethically questionable. In addition, conventional tests are complex, expensive and take ...

Coral Gables, FL (August 7, 2015)--Two new studies show that the tone of a candidate's voice can influence whether he or she wins office.

"Our analyses of both real-life elections and data from experiments show that candidates with lower-pitched voices are generally more successful at the polls," explains Casey Klofstad, associate professor of political science at the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences, who is corresponding author on both studies.

The first study, published online in Political Psychology, shows that candidates who ran in the 2012 U.S. ...

CRG researchers have proposed a new theory to explain the origin of whole genome duplication at the beginning of the yeast lineage. Yeasts are single-celled fungi that originated over 100 million years ago. The ability of these organisms to ferment carbohydrates is widely used for food and drink fermentation. Yeasts are also one of the most commonly used model organisms in research. For example, the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is used to make bread, wine and beer, was the first eukaryotic organism to be sequenced (in 1996) and is a key model organism for studying ...

Medulloblastoma, the most commonly occurring malignant brain tumor in children, can be classified into four subgroups--each with a different risk profile requiring subgroup-specific therapy. Currently, subgroup determination is done after surgical removal of the tumor. Investigators at Children's Hospital Los Angeles have now discovered that these subgroups can be determined non-invasively, using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). The paper will be published online by the journal Neuro-Oncology (Oxford Press) on August 7.

"By identification of the tumor subgroup ...

TORONTO - Hearing loss in adults is under treated despite evidence that hearing aid technology can significantly lessen depression and anxiety and improve cognitive functioning, according to a presentation at the American Psychological Association's 123rd Annual Convention.

"Many hard of hearing people battle silently with their invisible hearing difficulties, straining to stay connected to the world around them, reluctant to seek help," said David Myers, PhD, a psychology professor and textbook writer at Hope College in Michigan who lives with hearing loss.

In a ...

Philadelphia - A large randomized clinical trial of an emergency department (ED)-based program aimed at reducing incidents of excessive drinking and partner violence in women did not result in significant improvements in either risk factor, according to a new study from researchers at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Contrary to previous studies which found brief interventions in the ED setting to be effective for reducing alcohol consumption to safe levels and preventing subsequent injury among patients with hazardous drinking, the new ...

Capture and convert--this is the motto of carbon dioxide reduction, a process that stops the greenhouse gas before it escapes from chimneys and power plants into the atmosphere and instead turns it into a useful product.

One possible end product is methanol, a liquid fuel and the focus of a recent study conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory. The chemical reactions that make methanol from carbon dioxide rely on a catalyst to speed up the conversion, and Argonne scientists identified a new material that could fill this role. With ...