(Press-News.org) Washington, DC - August 20, 2015 - Swedish exchange students who studied in India and in central Africa returned from their sojourns with an increased diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in their gut microbiomes. The research is published 10 August in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

In the study, the investigators found a 2.6-fold increase in genes encoding resistance to sulfonamide, a 7.7-fold increase in trimethoprim resistance genes, and a 2.6-fold increase in resistance to beta-lactams, all of this without any exposure to antibiotics among the 35 exchange students. These resistance genes were not particularly abundant in the students prior to their travels, but the increases are nonetheless quite significant.

The germ of the research was concern about the burgeoning increase in antibiotic resistance. "I am a physician specializing in infectious diseases, and I have seen antibiotics that I could safely rely on ten years ago being unable to cure my patients," said principal investigator Anders Johansson, MD, PhD, Chief, Infection Control, Umeå University and the County Council of Våsterbotten, Sweden.

However, Johansson also questioned the conventional wisdom that overuse of antibiotics was entirely responsible for the surge in resistance, despite the fact that overuse is a huge problem. "Currently, I head an infection control department, and from this position it is very evident that resistance is no longer generated primarily in the hospital," he explained. Instead, patients bring bacteria carrying resistance genes into the hospital as part of their own microbial communities, he said. "We hypothesized that the gut microbiome of humans serves as a vehicle for moving many different resistance genes very large distances, even in the absence of antibiotic treatment."

And in fact, the increases the investigators observed in abundance and diversity of resistance genes occurred despite the fact that none of the students took antibiotics either before or during travel. The increase seen in resistance genes could have resulted from ingesting food containing resistant bacteria, or from contaminated water, the investigators write. Providing further support for the hypothesis that resistance genes increased during travel, genes for extended spectrum beta-lactamase, which dismembers penicillin and related antibiotics, was present in just one of the 35 students prior to travel, but in 12 students after they returned to Sweden.

Collecting samples of resistance genes was simple. "We asked students going abroad on exchange programs to provide a sample of their feces before and after traveling," said Johansson. But the study was different from previous studies of this issue in using metagenomics sequencing, a modern method. That enabled the investigators to sample the entire microbiome of each student, and to sequence every resistance gene therein, rather than focusing on resistance genes in those few bacterial species that grow well on culture plates.

"Our results spotlight that to reduce antibiotic resistance we need to minimize dispersal rates from the healthcare system, and importantly, at the societal level," said Johansson. Suppressing further spread after travelers return to their home countries is crucial, and depends, he added, upon having well-informed citizens and a well-functioning public health system.

INFORMATION:

The article can be found online at http://aac.asm.org/cgi/reprint/AAC.00933-15v1?ijkey=ApED6UHo8GluE&keytype=ref&siteid=asmjournals.

The American Society for Microbiology is the largest single life science society, composed of over 39,000 scientists and health professionals. ASM's mission is to advance the microbiological sciences as a vehicle for understanding life processes and to apply and communicate this knowledge for the improvement of health and environmental and economic well-being worldwide.

PHOENIX, Ariz. -- Aug. 20, 2015 -- A study by the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) and other major research institutes, found a new set of genes that can indicate improved survival after surgery for patients with pancreatic cancer. The study also showed that detection of circulating tumor DNA in the blood could provide an early indication of tumor recurrence.

In conjunction with the Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) Pancreatic Cancer Dream Team, the study was published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Communications.

Using whole-exome sequencing ...

If dark energy is hiding in our midst in the form of hypothetical particles called "chameleons," Holger Müller and his team at the University of California, Berkeley, plan to flush them out.

The results of an experiment reported in this week's issue of Science narrows the search for chameleons a thousand times compared to previous tests, and Müller, an assistant professor of physics, hopes that his next experiment will either expose chameleons or similar ultralight particles as the real dark energy, or prove they were a will-o'-the-wisp after all.

Dark energy ...

Management of boreal forests needs greater attention from international policy, argued forestry experts from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), Natural Resources Canada, and the University of Helsinki in Finland in a new article published this week in the journal Science. The article, which reviews recent research in the field, is part of a special issue on forests released in advance of the World Forestry Congress in September.

"Boreal forests have the potential to hit a tipping point this century," says IIASA Ecosystems Services and Management ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

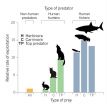

Humans are just one of many predators in this world, but a new study highlights how their intense tendency to target and kill adult prey, as well as other carnivores, sets them distinctly apart from other predators. As humans kill other species in their reproductive prime, there can be profound implications -- including widespread extinction and restructuring of food webs and ecosystems--in both terrestrial and marine systems. To evaluate the nature of human predation compared to nonhuman predation, Chris Darimont et al. conducted ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

In this special issue, the editors of Science invite experts to provide closer looks at how natural and human-induced environmental changes are affecting forests around the world, from the luscious, diverse forests of the tropics, to the pristine, resilient boreal forests of the north. The special issue is complemented by a package from Science's news department.

Amid extreme environmental and climate changes, Susan Trumbore and colleagues highlight the urgency of monitoring forest health, especially ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Amid continued difficulties around assessing bioweapons threats, especially given limited empirical data, Crystal Boddie and colleagues took another route to gauge their danger: the collective judgment of multiple experts. The experts' opinions on bioweapons-related risks were quite diverse, the Policy Forum authors say, adding to the challenge around developing a regulatory system for legitimate dual use research. Boddie et al. explain how they employed a Delphi Method study to query the beliefs and opinions of 59 experts ...

An examination of the immune genes of the southern African Khoe-San people has revealed a completely new kind of mutation, according to researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine. The gene variant likely contributes to healthier babies, although the variant can also lower resistance to disease.

The findings grew out of a long-term effort by Peter Parham, PhD, professor of structural biology and of microbiology and immunology, to understand how immune system genes make us reject organ transplants.

A paper detailing the findings will be published online ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Myriad regulations and certification requirements around the world are making it virtually impossible to use genetically engineered trees to combat catastrophic forest threats, according to a new policy analysis published this week in the journal Science.

In the United States, the time is ripe to consider regulatory changes, the authors say, because the federal government recently initiated an update of the overarching Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology, which governs use of genetic engineering.

North American forests are suffering ...

Are humans unsustainable 'super predators'?

Want to see what science now calls the world's "super predator"? Look in the mirror.

Research published today in the journal Science by a team led by Dr. Chris Darimont, the Hakai-Raincoast professor of geography at the University of Victoria, reveals new insight behind widespread wildlife extinctions, shrinking fish sizes and disruptions to global food chains.

"These are extreme outcomes that non-human predators seldom impose," Darimont's team writes in the article titled "The Unique Ecology of Human Predators."

"Our ...

Scientists have exposed a chink in the armour of disease-causing bugs, with a new discovery about a protein that controls bacterial defences.

Bacteria react to stressful situations - such as running out of nutrients, coming under attack from antibiotics or encountering a host body's immune system - with a range of defence mechanisms. These include constructing a resistant outer coat, growing defensive structures on their surface or producing enzymes that break down the DNA of an attacker.

The new research shows that a protein called sigma54 holds a bacterium's defences ...