(Press-News.org) LAWRENCE -- To look tougher, a weakling might shave their head and don a black leather jacket, combat boots and a scowl that tells the world, "don't mess with me."

But this kind of masquerade isn't limited to people. Researchers recently have revealed a timid South American woodpecker that evolved to assume the appearance of larger, tougher birds.

Visual mimicry lets the Helmeted Woodpecker (Dryocopus galeatus) live on the threatened Atlantic forest turf of two bigger birds -- the Lineated Dryocopus lineatus and Robust (Campephilus robustus) woodpeckers -- reducing the likelihood of being displaced in an area of foraging.

"Because of this, it has the advantage of foraging in the same areas as the birds it's mimicking, with those birds not being aggressive to this smaller woodpecker," said Mark Robbins, ornithology collection manager with the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute.

Robbins is co-author of a forthcoming paper in The Auk: Ornithological Advances showing that the Helmeted Woodpecker not only has deceived competing woodpeckers but also a previous generation of ornithologists who misclassified the bird based on the appearance of its plumage.

"It's very similar in pattern to these other woodpeckers," Robbins said. "In the 1980s, a monograph called 'Woodpeckers of the World' used museum specimens to assume relationships, and that has misled ornithologists across the board. Looking only at plumage has misguided us again and again."

One of Robbins' initial suspicions that the Helmeted Woodpecker wasn't a close relative of the Lineated Woodpecker came in 2010 at an international conference of ornithologists in São Paulo, Brazil.

"Some friends and I went off to see Brazilian birds in Atlantic Forest, and we really wanted to see Helmeted Woodpecker," he said. "One morning everyone was eating breakfast, but I was out by a lagoon. I heard its call, and went flying back inside through the doors saying, "There's a Helmeted Woodpecker!" So there was mass rush out the doors, and we spent over an hour following this woodpecker. I was thinking, 'I don't think this is a Dryocopus' -- and later thought it might be a member of the woodpecker genus."

Next, Robbins teamed with two colleagues, KU alumnus Brett Benz of the American Museum of Natural History (lead author on the Auk paper) and Kevin Zimmer of the Los Angeles County Museum. They sought a deeper understanding of the Helmeted Woodpecker, so they conducted genetic analysis of the bird using state-of-the-art technology at KU and the AMNH.

The question was whether the Helmeted Woodpecker belonged in the genus Dryocopus, as the bird's appearance would have it, or if a look at the woodpecker's DNA would place it more appropriately in genus Celeus.

"Background genetic work on placement of this bird was performed using tissue from toe pads from specimens at the L.A. County museum that had been collected over 60 years ago," Robbins said.

According to the authors, the results of the phylogenetic analyses "unequivocally" place the Helmeted Woodpecker within Celeus, showing the bird has matched its appearance with the "distantly related" Dryocopus lineatus with a "remarkable resemblance in plumage coloration and pattern."

Robbins said the Helmeted Woodpecker's smaller size and presumed submissive behavior are consistent with predictions derived from "evolutionary game theory" models and the "interspecific social dominance mimicry hypothesis."

Without modern genetic analysis, the Helmeted Woodpecker's evolutionary strategy of mimicking competing birds would have been hidden to science.

"Only in last 15 years or so could this have been revealed," Robbins said.

However, Robbins said that intense farming within the threatened Atlantic Forest habitat of the Helmeted Woodpecker has put survival of the species into question. He hopes the discovery of the bird's cryptic mimicry can call attention to destruction of its South American habitat.

"It's only found in southeastern Brazil, eastern Paraguay and extreme northern Argentina," Robbins said. "Much of that forest is gone. It's a biome that's been particularly degraded, and this woodpecker had declined considerably due to deforestation of the Atlantic Forests. It's threatened, has been misplaced phylogenetically and is mimicking bigger, more aggressive birds."

According to the KU researcher, the deforestation is due to farming of soybeans and sunflowers.

"There are some places in eastern Paraguay where this bird once lived in Atlantic Forest where now it looks more like Kansas," Robbins said.

INFORMATION:

The Monell Molecular Laboratory and the Cullman Research Facility in the Department of Ornithology at the American Museum of Natural History supported this research. The Rudkin Scholarship provided support for senior author Benz during his time at KU.

August 24, 2015 - In the western foothills and mountain rangelands of the U.S., wild larkspurs (Delphinium spp.) are a major cause of cattle losses.

For the most part, grazing cattle can self-regulate consumption of larkspurs and avoid toxicity problems. However, when cattle eat too much, too quickly, or they eat low amounts continuously, toxicity can occur. Symptoms of toxicity include muscle weakness. Cattle also can become non-ambulatory and die.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Animal Science, researchers with the USDA-ARS Poisonous Plant Research ...

In the animal world, sexual reproduction can involve males attempting to entice or force females to mate with them, even if they are not initially interested.

This male behaviour is driven by conflicts of interest over reproduction and exerts selective pressures on both sexes.

A new study on guppies led by the universities of Glasgow and Exeter has given scientists insight into how this behaviour can lead to physiological changes, much like those in athletes who train to perform better.

Dr Shaun Killen, of the University of Glasgow, said: "Sexual coercion of females ...

Boulder, Colo., USA - In the last few months, it has once more become clear that large earthquakes can solicit catastrophic landsliding. In the wake of the Nepal earthquake, the landslide community has been warning of persistent and damaging mass wasting due to monsoon rainfall in the epicentral area. However, very little is actually known about the legacy of earthquakes on steep, unstable hillslopes.

Using a dense time series of satellite images and air photos, Odin Marc and colleague reconstructed the history of landsliding in four mountain areas hit by large, shallow ...

Washington, DC - August 25, 2015 - Scientists in the Center for Infection and Immunity at the Mailman School of Public Health have discovered a new virus in seals that is the closest known relative of the human hepatitis A virus. The finding provides new clues on the emergence of hepatitis A. The research appears in the July/August issue of mBio, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

"Until now, we didn't know that hepatitis A had any close relatives and we thought that only humans and other primates could be infected by such viruses," ...

TAMPA, Fla. - Women who have inherited mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are more likely to develop breast cancer or ovarian cancer, especially at a younger age. Approximately 5 percent of women with breast cancer in the United States have mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 based on estimates in non-Hispanic white women. Moffitt Cancer Center researchers recently conducted the largest U.S. based study of BRCA mutation frequency in young black women diagnosed with breast cancer at or below age 50 and discovered they have a much higher BRCA mutation frequency than that previously ...

The burning of incense might need to come with a health warning. This follows the first study evaluating the health risks associated with its indoor use. The effects of incense and cigarette smoke were also compared, and made for some surprising results. The research was led by Rong Zhou of the South China University of Technology and the China Tobacco Guangdong Industrial Company in China, and is published in Springer's journal Environmental Chemistry Letters.

Incense burning is a traditional and common practice in many families and in most temples in Asia. It is not ...

Depressed people who turn to their smart phones for relief may only be making things worse.

A team of researchers, that included the dean of Michigan State University's College of Communication Arts and Sciences, found that people who substitute electronic interaction for the real-life human kind find little if any satisfaction.

In a paper published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior, the researchers argue that relying on a mobile phone to ease one's woes just doesn't work.

Using a mobile phone for temporary relief from negative emotions could worsen psychological ...

MADISON -- Colorful and expressive, the eyes are central to the way people interact with each other, as well as take in their surroundings.

That makes amblyopia -- more commonly known as "lazy eye" -- all the more obvious, but the physical manifestation of the most common cause of vision problems among children the world over is actually a brain disorder.

"Most often in amblyopia patients, one eye is better at focusing," says Bas Rokers, a University of Wisconsin-Madison psychology professor. "The brain prefers the information from that eye, and pushes down the signal ...

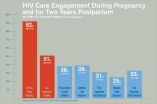

Pregnancy could be a turning point for HIV-infected women, when they have the opportunity to manage their infection, prevent transmission to their new baby and enter a long-term pattern of maintenance of HIV care after giving birth--but most HIV-infected women aren't getting that chance. That is the major message from a pair of new studies in Philadelphia, one published early online this month in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, and the other published in July in PLOS ONE.

The studies, led by a team of researchers from Drexel University and the Philadelphia Department ...

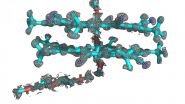

A team from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Indiana University combined two techniques to determine the structure of cyanostar, a new abiological molecule that captures unwanted negative ions in solutions.

When Semin Lee, a chemist and Beckman Institute postdoctoral fellow at Illinois, first created cyanostar at Indiana University, he knew the chemical properties, but couldn't determine the precise atomical structure. Lee synthesized cyanostar for its unique ability to bind with large, negatively charged ions, which could have applications such as ...