(Press-News.org) Before Ibuprofen can relieve your headache, it has to dissolve in your bloodstream. The problem is Ibuprofen, in its native form, isn't particularly soluble. Its rigid, crystalline structures -- the molecules are lined up like soldiers at roll call -- make it hard to dissolve in the bloodstream. To overcome this, manufacturers use chemical additives to increase the solubility of Ibuprofen and many other drugs, but those additives also increase cost and complexity.

The key to making drugs by themselves more soluble is not to give the molecular soldiers time to fall in to their crystalline structures, making the particle unstructured or amorphous.

Researchers from Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS) have developed a new system that can produce stable, amorphous nanoparticles in large quantities that dissolve quickly.

But that's not all. The system is so effective that it can produce amorphous nanoparticles from a wide range of materials, including for the first time, inorganic materials with a high propensity towards crystallization, such as table salt.

These unstructured, inorganic nanoparticles have different electronic, magnetic and optical properties from their crystalized counterparts, which could lead to applications in fields ranging from materials engineering to optics.

David A. Weitz, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics and Applied Physics and an associate faculty member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, describes the research in a paper published today in Science.

"This is a surprisingly simple way to make amorphous nanoparticles from almost any material," said Weitz. "It should allow us to quickly and easily explore the properties of these materials. In addition, it may provide a simple means to make many drugs much more useable."

The technique involves first dissolving the substances in good solvents, such as water or alcohol. The liquid is then pumped into a nebulizer, where compressed air moving twice the speed of sound sprays the liquid droplets out through very narrow channels. It's like a spray can on steroids. The droplets are completely dried between one to three microseconds from the time they are sprayed, leaving behind the amorphous nanoparticle.

At first, the amorphous structure of the nanoparticles was perplexing, said Esther Amstad, a former postdoctoral fellow in Weitz' lab and current assistant professor at EPFL in Switzerland. Amstad is the paper's first author. Then, the team realized that the nebulizer's supersonic speed was making the droplets evaporate much faster than expected.

"If you're wet, the water is going to evaporate faster when you stand in the wind," said Amstad. "The stronger the wind, the faster the liquid will evaporate. A similar principle is at work here. This fast evaporation rate also leads to accelerated cooling. Just like the evaporation of sweat cools the body, here the very high rate of evaporation causes the temperature to decrease very rapidly, which in turn slows down the movement of the molecules, delaying the formation of crystals."

These factors prevent crystallization in nanoparticles, even in materials that are highly prone to crystallization, such as table salt. The amorphous nanoparticles are exceptionally stable against crystallization, lasting at least seven months at room temperature.

The next step, Amstad said, is to characterize the properties of these new inorganic amorphous nanoparticles and explore potential applications.

"This system offers exceptionally good control over the composition, structure, and size of particles, enabling the formation of new materials," said Amstad. " It allows us to see and manipulate the very early stages of crystallization of materials with high spatial and temporal resolution, the lack of which had prevented the in-depth study of some of the most prevalent inorganic biomaterials. This systems opens the door to understanding and creating new materials."

INFORMATION:

This research was coauthored by Manesh Gopinadhan, Christian Holtze, Chinedum O. Osuji, Michael P. Brenner, the Glover Professor of Applied Mathematics and Applied Physics and Professor of Physics, and Frans Spaepen, the John C. and Helen F. Franklin Professor of Applied Physics. It was supported by the National Science Foundation, Harvard MRSEC and BASF through the North American Center for Research on Advanced Materials (NORA), headed by Dr. Marc Schroeder.

As President Obama and high-level representatives of other nations converge in Anchorage, Alaska on August 30-31 for the Conference on Global Leadership in the Arctic: Cooperation, Innovation, Engagement and Resilience (GLACIER), hosted by the U.S. Department of State, top U.S. climate scientists urge policymakers to address the critical problem of the thawing permafrost in the Arctic region.

Arctic permafrost - ground that has been frozen for many thousands of years - is now thawing because of global climate change, and the results could be disastrous and irreversible. ...

Degenerating neurons in patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) measurably responded to an experimental gene therapy in which nerve growth factor (NGF) was injected into their brains, report researchers at University of California, San Diego School of Medicine in the current issue of JAMA Neurology.

The affected neurons displayed heightened growth, axonal sprouting and activation of functional markers, said lead author Mark H. Tuszynski, MD, PhD, professor in the Department of Neurosciences, director of the UC San Diego Translational Neuroscience Institute and a neurologist ...

Collisions with wind turbines kill about 100 golden eagles a year in some locations, but a new study that maps both potential wind-power sites and nesting patterns of the birds reveals sweet spots, where potential for wind power is greatest with a lower threat to nesting eagles.

Brad Fedy, a professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo, and Jason Tack, a PhD student at Colorado State University, took nesting data from a variety of areas across Wyoming, and created models using a suite of environmental variables and referenced them against areas ...

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. -- Florida State University researchers have taken a big step forward in the fight against cancer with a discovery that could open up the door for new research and treatment options.

Fanxiu Zhu, the FSU Margaret and Mary Pfeiffer Endowed Professor for Cancer Research, and his team uncovered a viral protein in the cell that inhibits the major DNA sensor and thus the body's response to viral infection, suggesting that this cellular pathway could be manipulated to help a person fight infection, cancer or autoimmune diseases.

They named the protein KicGas.

"We ...

Brief intervals of exercise during otherwise sedentary periods may offset the lack of more sustained exercise and could protect children against diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer, according to a small study by researchers at the National Institutes of Health

Children who interrupted periods of sitting with three minutes of moderate-intensity walking every half hour had lower levels of blood glucose and insulin, compared to periods when they remained seated for three hours. Moreover, on the day they walked, the children did not eat any more at lunch than on ...

Washington, DC--People who developed Type 2 diabetes tended to take more antibiotics in the years leading up to the diagnosis than people who did not have the condition, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

A person develops diabetes, which is characterized by high blood sugar levels, when the individual cannot produce enough of the hormone insulin or insulin does not work properly to clear sugar from the bloodstream.

More than 29 million Americans have diabetes, according to the Society's Endocrine ...

Washington, DC--Taking 3-minute breaks to walk in the middle of a TV marathon or other sedentary activity can improve children's blood sugar compared to continuously sitting, according to a new National Institutes of Health (NIH) study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (JCEM).

A sedentary lifestyle can put children at risk of developing pediatric obesity and metabolic health problems such as diabetes. Nearly 17 percent of children and teens nationwide are obese, according to the Society's Endocrine Facts and Figures report. ...

Washington, DC--For years after it was administered, growth hormone continued to reduce the risk of fractures and helped maintain bone density in postmenopausal women who had osteoporosis, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Osteoporosis is a progressive condition that causes the bones to become weak and more likely to break. More than 10 million American adults have osteoporosis, and 80 percent of the people being treated for the condition nationwide are women, according to the Society's Endocrine ...

NASA's Aqua satellite and NOAA's GOES-West satellite provided temperature and cloud data on newborn Tropical Storm Jimena in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Data from both satellites show the storm continues to consolidate.

Tropical Depression 13E formed about 865 miles (1,390 km) south-southwest of the southern tip of Baja California, Mexico at 5 p.m. EDT (2100 UTC) on August 26. Six hours later, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Jimena at 11 p.m. EDT.

A false-colored infrared image from Aug. 27 at 09:47 UTC (4:57 a.m. EDT) showed high, cold, strong thunderstorms ...

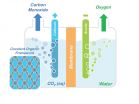

A molecular system that holds great promise for the capture and storage of carbon dioxide has been modified so that it now also holds great promise as a catalyst for converting captured carbon dioxide into valuable chemical products. Researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have incorporated molecules of carbon dioxide reduction catalysts into the sponge-like crystals of covalent organic frameworks (COFs). This creates a molecular system that not only absorbs carbon dioxide, but also selectively reduces ...