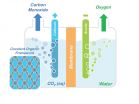

(Press-News.org) A molecular system that holds great promise for the capture and storage of carbon dioxide has been modified so that it now also holds great promise as a catalyst for converting captured carbon dioxide into valuable chemical products. Researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)'s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have incorporated molecules of carbon dioxide reduction catalysts into the sponge-like crystals of covalent organic frameworks (COFs). This creates a molecular system that not only absorbs carbon dioxide, but also selectively reduces it to carbon monoxide, which serves as a primary building block for a wide range of chemical products including fuels, pharmaceuticals and plastics.

"There have been many attempts to develop homogeneous or heterogeneous catalysts for carbon dioxide, but the beauty of using COFs is that we can mix-and-match the best of both worlds, meaning we have molecular control by choice of catalysts plus the robust crystalline nature of the COF," says Christopher Chang, a chemist with Berkeley Lab's Chemical Sciences Division, and a co-leader of this study. "To date, such porous materials have mainly been used for carbon capture and separation, but in showing they can also be used for carbon dioxide catalysis, our results open up a huge range of potential applications in catalysis and energy."

Chang and Omar Yaghi, a chemist with Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division who invented COFs, are the corresponding authors of a paper in Science that describes this research in detail. The paper is titled "Covalent organic frameworks comprising cobalt porphyrins for catalytic CO2 reduction in water." Lead authors are Song Lin, Christian Diercks and Yue-Biao Zhang. Other co-authors are Nikolay Kornienko, Eva Nichols, Yingbo Zhao, Aubrey Paris, Dohyung Kim and Peidong Yang.

Chang and Yaghi both hold appointments with the University of California (UC) Berkeley. Chang is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator. Yaghi is co-director of the Kavli Energy NanoScience Institute (Kavli-ENSI) at UC Berkeley.

The notoriety of carbon dioxide for its impact on the atmosphere and global climate change has overshadowed its value as an abundant, renewable, nontoxic and nonflammable source of carbon for the manufacturing of widely used chemical products. With the reduction of atmospheric carbon dioxide emissions in mind, Yaghi and his research group at the University of Michigan in 2005 designed and developed the first COFs as a means of separating carbon dioxide from flue gases. A COF is a porous three-dimensional crystal consisting of a tightly folded, compact framework that features an extraordinarily large internal surface area - a COF the size of a sugar cube were it to be opened and unfolded would blanket a football field. The sponge-like quality of a COF's vast internal surface area enables the system to absorb and store enormous quantities of targeted molecules, such as carbon dioxide.

Now, through another technique developed by Yaghi, called "reticular chemistry," which enables molecular systems to be "stitched" into netlike structures that are held together by strong chemical bonds, the Berkeley Lab researchers were able to embed the molecular backbone of COFs with a porphyrin catalyst, a ring-shaped organic molecule with a cobalt atom at its core. Porphyrins are electrical conductors that are especially proficient at transporting electrons to carbon dioxide.

"A key feature of COFs is the ability to modify chemically active sites at will with molecular-level control by tuning the building blocks constituting a COF's framework," Yaghi says. "This affords a significant advantage over other solid-state catalysts where tuning the catalytic properties with that level of rational design remains a major challenge. Because the porphyrin COFs are stable in water, they can operate in aqueous electrolyte with high selectivity over competing water reduction reactions, an essential requirement for working with flue gas emissions."

In performance tests, the porphyrin COFs displayed exceptionally high catalytic activity - a turnover number up to 290,000, meaning one porphyrin COF can reduce 290,000 molecules of carbon dioxide to carbon monoxide every second. This represents a 60-fold increase over the catalytic activity of molecular cobalt porphyrin catalyst and places porphyrin COFs among the fastest and most efficient catalysts of all known carbon dioxide reduction agents. Furthermore, the research team believes there's plenty of room for further improving porphyrin COF performances.

"We're now seeking to increase the number of electroactive cobalt centers and achieve lower over-potentials while maintaining high activity and selectivity for carbon dioxide reduction over proton reduction," Chang says. "In addition we are working towards expanding the types of value-added carbon products that can be made using COFs and related frameworks."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the DOE Office of Science in part through its Energy Frontier Research Center (EFRC) program. The porphyrin COFs were characterized through X-ray absorption measurements performed at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world's most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab's scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. For more, visit http://www.lbl.gov.

DOE's Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov/.

Researchers reporting in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on August 27 have evidence in support of a clearly defined depth limit for deep-sea fishing in Europe. The findings come just as the European Union considers controversial new legislation to manage deep-sea fisheries, including a ban on trawling below 600 meters.

"The most notable thing to consider about our findings is that the trend in catch composition over the depth range of 600 to 800 meters shows that collateral ecological impacts are significantly increasing while the commercial gain per unit effort ...

Isaac Newton was a classic neurotic. He was a brooder and a worrier, prone to dwelling on the scientific problems before him as well as his childhood sins. But Newton also had creative breakthroughs--thoughts on physics so profound that they are still part of a standard science education.

In a Trends in Cognitive Sciences Opinion paper published August 27, psychologists present a new theory for why neurotic unhappiness and creativity go hand-in-hand. The authors argue that the part of the brain responsible for self-generated thought is highly active in neuroticism, which ...

Researchers at the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute at Virginia Tech have uncovered key cellular functions that help regulate inflammation -- a discovery that could have important implications for the treatment of allergies, heart disease, and certain forms of cancer.

The discovery, to be published in the Oct. 6 issue of the journal Structure, explains how two particular proteins, Tollip and Tom1, work together to contribute to the turnover of cell-surface receptor proteins that trigger inflammation.

"The inflammatory response can be a double-edged sword," said Daniel ...

Mobility between different physical environments in the cell nucleus regulates the daily oscillations in the activity of genes that are controlled by the internal biological clock, according to a study that is published in the journal Molecular Cell. Eventually, these findings may lead to novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of diseases linked with disrupted circadian rhythm.

So called clock-controlled - or circadian - genes are part of the internal biological clock, allowing humans and other light-sensitive organisms to adjust their daily activity to the cycle ...

Cold Spring Harbor, NY - When a large combat unit, widely dispersed in dense jungle, goes to battle, no single soldier knows precisely how his actions are affecting the unit's success or failure. But in modern armies, every soldier is connected via an audio link that can instantly receive broadcasts - reporting both positive and negative surprises - based on new intelligence. The real-time broadcasts enable dispersed troops to learn from these reports and can be critical since no solider has an overview of the entire unit's situation.

Similarly, as neuroscientists at Cold ...

LA JOLLA--Every organism--from a seedling to a president--must protect its DNA at all costs, but precisely how a cell distinguishes between damage to its own DNA and the foreign DNA of an invading virus has remained a mystery.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered critical details of how a cell's response system tells the difference between these two perpetual threats. The discovery could help in the development of new cancer-selective viral therapies and may help explain why aging and certain diseases seem to open the door to viral infections.

"Our ...

Working with human cancer cell lines and mice, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and elsewhere have found a way to trigger a type of immune system "virus alert" that may one day boost cancer patients' response to immunotherapy drugs. An increasingly promising focus of cancer research, the drugs are designed to disarm cancer cells' ability to avoid detection and destruction by the immune system.

In a report on the work published in the Aug. 27 issue of Cell, the Johns Hopkins-led research team says it has found a core group of genes related to both ...

Understanding exactly what is taking place inside a single cell is no easy task. For DNA, amplification techniques are available to make the task possible, but for other substances such as proteins and small molecules, scientists generally have to rely on statistics generated from many different cells measured together. Unfortunately, this means they cannot look at what is happening in each individual cell.

Now, thanks to seven years of work done at the RIKEN Quantitative Biology Center and Hiroshima University, scientists can take a peek into a single plant cell and--within ...

In experiments with mouse tissue, UC San Francisco researchers have discovered that the adaptive immune system, generally associated with fighting bacterial and viral infections, plays an active role in guiding the normal development of mammary glands, the only organs--in female humans as well as mice--that develop predominately after birth, beginning at puberty.

The scientists say the findings have implications not only for understanding normal organ development, but also for cancer and tissue-regeneration research, as well as in the highly active field of cancer immunotherapy, ...

Philadelphia, PA, Aug 27, 2015 - Having twins accounts for only 1.5% of all births but 25% of preterm births, the leading cause of infant mortality worldwide. Successful strategies for reducing singleton preterm births include prophylactic use of progesterone and cervical cerclage in patients with a prior history of preterm birth. To investigate whether the use of a cervical pessary might reduce premature births of twins, an international team of researchers conducted a large, multicenter, international randomized clinical trial (RCT) of approximately 1200 twin pregnancies. ...