(Press-News.org) Researchers at the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute at Virginia Tech have uncovered key cellular functions that help regulate inflammation -- a discovery that could have important implications for the treatment of allergies, heart disease, and certain forms of cancer.

The discovery, to be published in the Oct. 6 issue of the journal Structure, explains how two particular proteins, Tollip and Tom1, work together to contribute to the turnover of cell-surface receptor proteins that trigger inflammation.

"The inflammatory response can be a double-edged sword," said Daniel Capelluto, an associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Science, a Fralin Life Science Institute affiliate, and Fellow in the Virginia Bioinformatics Institute. "At appropriate levels, the inflammatory response protects your body from foreign materials, but if it is not properly regulated it can lead to severe, chronic conditions."

Inflammation plays a role in major health problems such as heart disease, diabetes, Alzheimer's disease, and cancer, as well as psychiatric diseases such as depression and autism spectrum disorder, according to the National Institutes of Health.

The discovery by Virginia Bioinformatics Institute researchers reveals protein structural changes within cells that could help inform treatments.

When the body is attacked by a virus or other germs, specialized cells secrete pro-inflammatory signals recognized by interleukin-1 receptors on the surface of specialized cells, triggering the release of additional pro-inflammatory molecules which amplify the response against pathogens.

These receptors continue to promote inflammation as long as they detect that initial "alert" signal.

When a healthy level of inflammation is reached, the receptor proteins need to be removed and delivered to intracellular compartments called endosomes for containment and further clearance.

"We knew that Tollip and Tom1 worked together on the surface of the endosome to transport these receptors for degradation," said Capelluto. "But it wasn't clear how they fit together structurally or why two separate proteins were needed to fulfill this cargo transport function."

Using a combination of techniques, including two- and three-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, surface plasmon resonance, and fluorescence cell microscopy, Capelluto's team determined that Tollip's association with Tom1 drastically changes Tollip's structure, forming a unit that can potentially transport cargo much more efficiently than either protein on its own.

Tollip contains a functional module called C2, which anchors the protein to the surface of the endosomal membrane to pick up cargo. However, with C2 engaged in holding Tollip's position, the protein's load-bearing capacity is limited.

But when Tom1 binds to Tollip, Tollip's C2 domain is no longer directly associated with the endosomal membrane, potentially shifting its function from "landing gear" to "cargo bay."

The resulting unit can carry larger loads and assist in the clearance of unneeded receptor proteins more efficiently.

The discovery expands fundamental understanding of how the body regulates its inflammatory response and may inform efforts to treat diseases associated with chronic inflammation such as heart disease, stroke, and colon cancer, the researchers said.

INFORMATION:

The project was developed by Virginia Tech researchers Shuyan Xiao, a postdoctoral associate; Mary K. Brannon, a master's student in biological sciences; Xiaolin Zhao, a doctoral student in biological sciences; Kristen Fread, an undergraduate student of biochemistry; and Carla Finkielstein, an associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Science. Jeffrey Ellena, a senior scientist of chemistry; and John Bushweller, a professor of molecular physiology and biological physics, both at the University of Virginia; and Geoffrey Armstrong, a research associate at the University of Colorado-Boulder, were also on the research team.

Mobility between different physical environments in the cell nucleus regulates the daily oscillations in the activity of genes that are controlled by the internal biological clock, according to a study that is published in the journal Molecular Cell. Eventually, these findings may lead to novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of diseases linked with disrupted circadian rhythm.

So called clock-controlled - or circadian - genes are part of the internal biological clock, allowing humans and other light-sensitive organisms to adjust their daily activity to the cycle ...

Cold Spring Harbor, NY - When a large combat unit, widely dispersed in dense jungle, goes to battle, no single soldier knows precisely how his actions are affecting the unit's success or failure. But in modern armies, every soldier is connected via an audio link that can instantly receive broadcasts - reporting both positive and negative surprises - based on new intelligence. The real-time broadcasts enable dispersed troops to learn from these reports and can be critical since no solider has an overview of the entire unit's situation.

Similarly, as neuroscientists at Cold ...

LA JOLLA--Every organism--from a seedling to a president--must protect its DNA at all costs, but precisely how a cell distinguishes between damage to its own DNA and the foreign DNA of an invading virus has remained a mystery.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered critical details of how a cell's response system tells the difference between these two perpetual threats. The discovery could help in the development of new cancer-selective viral therapies and may help explain why aging and certain diseases seem to open the door to viral infections.

"Our ...

Working with human cancer cell lines and mice, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and elsewhere have found a way to trigger a type of immune system "virus alert" that may one day boost cancer patients' response to immunotherapy drugs. An increasingly promising focus of cancer research, the drugs are designed to disarm cancer cells' ability to avoid detection and destruction by the immune system.

In a report on the work published in the Aug. 27 issue of Cell, the Johns Hopkins-led research team says it has found a core group of genes related to both ...

Understanding exactly what is taking place inside a single cell is no easy task. For DNA, amplification techniques are available to make the task possible, but for other substances such as proteins and small molecules, scientists generally have to rely on statistics generated from many different cells measured together. Unfortunately, this means they cannot look at what is happening in each individual cell.

Now, thanks to seven years of work done at the RIKEN Quantitative Biology Center and Hiroshima University, scientists can take a peek into a single plant cell and--within ...

In experiments with mouse tissue, UC San Francisco researchers have discovered that the adaptive immune system, generally associated with fighting bacterial and viral infections, plays an active role in guiding the normal development of mammary glands, the only organs--in female humans as well as mice--that develop predominately after birth, beginning at puberty.

The scientists say the findings have implications not only for understanding normal organ development, but also for cancer and tissue-regeneration research, as well as in the highly active field of cancer immunotherapy, ...

Philadelphia, PA, Aug 27, 2015 - Having twins accounts for only 1.5% of all births but 25% of preterm births, the leading cause of infant mortality worldwide. Successful strategies for reducing singleton preterm births include prophylactic use of progesterone and cervical cerclage in patients with a prior history of preterm birth. To investigate whether the use of a cervical pessary might reduce premature births of twins, an international team of researchers conducted a large, multicenter, international randomized clinical trial (RCT) of approximately 1200 twin pregnancies. ...

DURHAM, N.H. - Researchers at the University of New Hampshire are turning to an unusual source --otoliths, the inner ear bones of fish -- to identify the nursery grounds of winter flounder, the protected estuaries where the potato chip-sized juveniles grow to adolesence. The research, recently published in the journal Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, could aid the effort to restore plummeting winter flounder populations along the East Coast of the U.S.

In addition to showing the age of a fish, much like the rings in the cross-section of a tree, otoliths ...

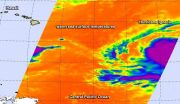

When cloud top temperatures get colder, the uplift in tropical cyclones gets stronger and the thunderstorms that make up the tropical cyclones have more strength. NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Hurricane Ignacio and infrared data revealed cloud top temperatures had cooled from the previous day.

Ignacio strengthened to a hurricane at 11 p.m. EDT on August 26. It became the seventh hurricane of the Eastern Pacific Ocean hurricane season.

A false-colored infrared image of Hurricane Ignacio was made at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena California, using data ...

Researchers from the Gladstone Institutes have revealed that HIV does not cause AIDS by the virus's direct effect on the host's immune cells, but rather through the cells' lethal influence on one another.

HIV can either be spread through free-floating virus that directly infect the host immune cells or an infected cell can pass the virus to an uninfected cell. The second method, cell to cell transmission, is 100 to 1000 times more efficient, and the new study shows that it is only this method that sets off a cellular chain reaction that ends in the newly infected cells ...