(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA--Every organism--from a seedling to a president--must protect its DNA at all costs, but precisely how a cell distinguishes between damage to its own DNA and the foreign DNA of an invading virus has remained a mystery.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered critical details of how a cell's response system tells the difference between these two perpetual threats. The discovery could help in the development of new cancer-selective viral therapies and may help explain why aging and certain diseases seem to open the door to viral infections.

"Our study reveals fundamental mechanisms that distinguish DNA breaks at cellular and viral genomes to trigger different responses that protect the host," says Clodagh O'Shea, associate professor and senior author of the work, which was published in Cell on August 27, 2015. "The findings may also explain why certain conditions like aging, cancer chemotherapy and inflammation make us more susceptible to viral infection."

Many factors (such as radiation) can cause a break in our DNA. The team detailed how a cluster of proteins--collectively called the MRN complex--detects both DNA and viral breaks and amplifies its response through histones, packaging proteins that wrap genetic material into small bundles like Styrofoam peanuts. MRN starts a domino effect, activating histones on surrounding chromosomes, which summons a cascade of additional proteins, resulting in a cell-wide, all-hands-on-deck alarm to help mend the DNA.

If the cell can't fix the DNA break, it will induce cell death--a self-destruct mechanism that helps to prevent mutated cells from replicating (and thus prevents tumor growth).

"What's interesting is that even a single break transmits a global signal through the cell, halting cell division and growth," says O'Shea. "This response prevents replication so the cell doesn't pass on a break."

When it comes to defending against DNA viruses, however, the Salk team found something interesting: the cell's response system begins the same way (with MRN detecting either DNA or viral breaks) but never progresses to the global alarm signal in the case of the virus.

Typically, a common DNA virus enters the cell's nucleus and turns on genes to replicate its own DNA. The cell detects the unauthorized replication and the MRN complex grabs and selectively neutralizes viral DNA without triggering a global response that would arrest or kill the cell. The difference in the intensity of its response, says the Salk researchers, is akin to sending a text message for a local flood warning (in the case of the DNA virus) versus a citywide tsunami siren (DNA break). The MRN response to the virus stays localized and only selectively prevents viral, but not cellular, replication. If every incoming virus spurred a similarly strong response, points out O'Shea, our cells would be frequently paused, hampering our growth.

And when both threats to the genome are present, MRN will activate the massive response at the DNA break; no MRN is left to respond to the virus. This means the virus is effectively ignored while the cell responds to the more massive alarm.

"The requirement of MRN for sensing both cellular and viral genome breaks has profound consequences," says O'Shea. "When MRN is recruited to cellular DNA breaks, it can no longer sense and respond to incoming viral genomes. Thus, the act of responding to cellular genome breaks inactivates the host's defenses to viral replication."

O'Shea says this may explain why people with conditions resulting in high levels of cellular DNA damage (e.g., cancer, chemotherapy, inflammation and aging) are more susceptible to viral infections.

"Having damaged DNA compromises our cells' ability to fight viral infection, while having healthy DNA boosts our cells' ability to catch viral DNA," says Govind Shah, first author of the new work and a former research associate at the Salk Institute. "Our work implies that we may be able to engineer viruses that selectively kill cancer cells."

The O'Shea lab aims to use this new knowledge to create novel viruses that are destroyed in normal cells but replicate specifically in cancer cells. Unlike normal cells, cancer cells almost always have very high levels of DNA damage. In cancer cells, MRN is already so preoccupied with responding to DNA breaks in cancer cells that an engineered virus could sneak in undetected.

"Cancer cells by definition have high mutation rates and genomic instability even at the very earliest stages, so you could imagine building a virus that could destroy even the earliest lesions and be used as a prophylactic," says O'Shea.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by the NCI, the Marshall Heritage Foundation, the Price Family Foundation, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the William Scandling Trust and the Chapman Charitable Trust.

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probes fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative, and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines. Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine pioneer Jonas Salk, MD, the Institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

Working with human cancer cell lines and mice, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and elsewhere have found a way to trigger a type of immune system "virus alert" that may one day boost cancer patients' response to immunotherapy drugs. An increasingly promising focus of cancer research, the drugs are designed to disarm cancer cells' ability to avoid detection and destruction by the immune system.

In a report on the work published in the Aug. 27 issue of Cell, the Johns Hopkins-led research team says it has found a core group of genes related to both ...

Understanding exactly what is taking place inside a single cell is no easy task. For DNA, amplification techniques are available to make the task possible, but for other substances such as proteins and small molecules, scientists generally have to rely on statistics generated from many different cells measured together. Unfortunately, this means they cannot look at what is happening in each individual cell.

Now, thanks to seven years of work done at the RIKEN Quantitative Biology Center and Hiroshima University, scientists can take a peek into a single plant cell and--within ...

In experiments with mouse tissue, UC San Francisco researchers have discovered that the adaptive immune system, generally associated with fighting bacterial and viral infections, plays an active role in guiding the normal development of mammary glands, the only organs--in female humans as well as mice--that develop predominately after birth, beginning at puberty.

The scientists say the findings have implications not only for understanding normal organ development, but also for cancer and tissue-regeneration research, as well as in the highly active field of cancer immunotherapy, ...

Philadelphia, PA, Aug 27, 2015 - Having twins accounts for only 1.5% of all births but 25% of preterm births, the leading cause of infant mortality worldwide. Successful strategies for reducing singleton preterm births include prophylactic use of progesterone and cervical cerclage in patients with a prior history of preterm birth. To investigate whether the use of a cervical pessary might reduce premature births of twins, an international team of researchers conducted a large, multicenter, international randomized clinical trial (RCT) of approximately 1200 twin pregnancies. ...

DURHAM, N.H. - Researchers at the University of New Hampshire are turning to an unusual source --otoliths, the inner ear bones of fish -- to identify the nursery grounds of winter flounder, the protected estuaries where the potato chip-sized juveniles grow to adolesence. The research, recently published in the journal Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, could aid the effort to restore plummeting winter flounder populations along the East Coast of the U.S.

In addition to showing the age of a fish, much like the rings in the cross-section of a tree, otoliths ...

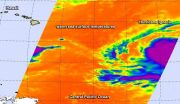

When cloud top temperatures get colder, the uplift in tropical cyclones gets stronger and the thunderstorms that make up the tropical cyclones have more strength. NASA's Aqua satellite passed over Hurricane Ignacio and infrared data revealed cloud top temperatures had cooled from the previous day.

Ignacio strengthened to a hurricane at 11 p.m. EDT on August 26. It became the seventh hurricane of the Eastern Pacific Ocean hurricane season.

A false-colored infrared image of Hurricane Ignacio was made at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena California, using data ...

Researchers from the Gladstone Institutes have revealed that HIV does not cause AIDS by the virus's direct effect on the host's immune cells, but rather through the cells' lethal influence on one another.

HIV can either be spread through free-floating virus that directly infect the host immune cells or an infected cell can pass the virus to an uninfected cell. The second method, cell to cell transmission, is 100 to 1000 times more efficient, and the new study shows that it is only this method that sets off a cellular chain reaction that ends in the newly infected cells ...

At a time when cancer drug prices are rising rapidly, an innovative new study provides the framework for establishing value-based pricing for all new oncology drugs entering the marketplace. Using a highly sophisticated economic model, researchers from Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and Georgia Institute of Technology used an example of a new lung cancer drug. The study findings will be published August 27, 2015 in JAMA Oncology.

Researchers focused their investigation on a drug called necitumumab, which is awaiting approval from the U.S. Food and Drug ...

Use of the 21-gene recurrence test score was associated with lower chemotherapy use in high-risk patients and greater use of chemotherapy in low-risk patients compared with not using the test among a large group of Medicare beneficiaries, according to an article published online by JAMA Oncology.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend considering chemotherapy in estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, node-negative breast cancer for all but the smallest tumors. Several studies have suggested the 21-gene recurrence score assay (testing) is cost-effective ...

Microfocused ultrasound (MFU) treatment to tighten and lift skin on the face and neck appeared to be safe for patients with darker skin types in a small study that resulted in only a few temporary adverse effects, according to a report published online by JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery.

Normal aging results in changes in the skin and underlying connective tissue. A system that uses MFU together with ultrasound visualization was developed to treat lax, aging skin. Previous clinical trials have shown the system to be a safe and effective noninvasive aesthetic treatment, according ...