INFORMATION:

Other co-authors are professor Joshua Lawler and doctoral student Meghan Halabisky, both in the UW's School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, and Alan Hamlet at the University of Notre Dame. All co-authors are members of a multi-institutional group studying wetlands adaptation and conservation in the face of climate change that produced a report for the Northwest Climate Science Center and a research brief for Mount Rainier National Park.

The new study was funded by the Department of the Interior's Northwest Climate Science Center, the David H. Smith Conservation Research Fellowship Program, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Pacific Northwest Landscape Conservation Cooperative.

For more information, contact Lee at 206-616-5347 or leesy@uw.edu or Ryan at 360-685-3640 or moryan@uw.edu. END

Climate change could leave Pacific Northwest amphibians high and dry

2015-09-04

(Press-News.org) Far above the wildfires raging in Washington's forests, a less noticeable consequence of this dry year is taking place in mountain ponds. The minimal snowpack and long summer drought that have left the Pacific Northwest lowlands parched also affect the region's amphibians due to loss of mountain pond habitat.

According to a new paper published Sept. 2 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, this summer's severe conditions may be the new normal within just a few decades.

"This year is an analog for the 2070s in terms of the conditions of the ponds in response to climate," said Se-Yeun Lee, research scientist at University of Washington's Climate Impacts Group and one of the lead authors of the study.

Current conditions provide a preview of how that will play out.

"We've seen that the lack of winter snowpack and high summer temperatures have resulted in massive breeding failures and the death of some adult frogs," said co-author Wendy Palen, an associate professor at Canada's Simon Fraser University who has for many years studied mountain amphibians in the Pacific Northwest. "More years like 2015 do not bode well for the frogs."

Mountain ponds are oases in the otherwise harsh alpine environment. Brilliant green patches amid the rocks and heather, the ponds are breeding grounds for Cascades frogs, toads, newts and several other salamanders, and watering holes for species ranging from shrews to mountain lions. They are also the cafeterias of the alpine for birds, snakes and mammals that feed on the invertebrates and amphibians that breed in high-altitude ponds.

The authors developed a new model that forecasts changes to four different types of these ecosystems: ephemeral, intermediate, perennial and permanent wetlands. Results showed that climate-induced reductions in snowpack, increased evaporation rates, longer summer droughts and other factors will likely lead to the loss or rapid drying of many of these small but ecologically important wetlands.

According to the study, more than half of the intermediate wetlands are projected to convert to fast-drying ephemeral wetlands by the year 2080. These most vulnerable ponds are the same ones that now provide the best habitat for frogs and salamanders.

At risk are unique species such as the Cascades frog, which is currently being evaluated for listing under the Endangered Species Act. Found only at high elevations in Washington, Oregon and California, Cascades frogs can live for more than 20 years and can survive under tens of feet of snow. During the mating season, just after ponds thaw, the males make chuckling sounds to attract females.

"They are the natural jesters of the alpine, incredibly tough but incredibly funny and charismatic," said Maureen Ryan, the other lead author, a former UW postdoctoral researcher who is now a senior scientist with Conservation Science Partners.

The team adapted methods developed for forecasting the effects of climate change on mountain streams. Wetlands usually receive little attention since they are smaller and often out of sight. Yet despite their hidden nature, ponds and wetlands are globally important ecosystems that help store water and carbon, filter pollution, convert nutrients and provide food and habitat to a huge range of migratory and resident species. Their sheer numbers -- in the tens of thousands across the Pacific Northwest mountain ranges -- make them ecologically significant.

"It's hard to truly quantify the effects of losing these ponds because they provide so many services and resources to so many species, including us," Ryan said. "Many people have predicted that they are especially vulnerable to climate change. Our study shows that these concerns are warranted."

Land managers can use the study's maps to prepare for climate change. For example, Ryan and co-authors are working with North Cascades National Park, where park biologists are using the wetland projections to evaluate and update priorities for managing introduced fish and restoring natural alpine lake habitat.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Highly effective seasickness treatment on the horizon

2015-09-04

The misery of motion sickness could be ended within five to ten years thanks to a new treatment being developed by scientists.

The cause of motion sickness is still a mystery but a popular theory among scientists says it is to do with confusing messages received by our brains from both our ears and eyes, when we are moving.

It is a very common complaint and has the potential to affect all of us, meaning we get a bit queasy on boats or rollercoasters. However, around three in ten people experience hard-to-bear motion sickness symptoms, such as dizziness, severe nausea, ...

Spasm at site of atherosclerotic coronary artery narrowing increases risk of heart attack

2015-09-04

This news release is available in Japanese.

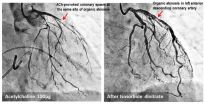

Researchers at Kumamoto University in Japan have found that patients with coronary spasm have a higher risk of experiencing future heart attack particularly when a spasm occurs at the site of atherosclerotic coronary artery narrowing, i.e., coronary atherosclerotic stenosis.

Angina is caused by the narrowing of the blood vessels that carry blood to the heart, and vasospastic angina patients account for about 40% of all angina patients. The incidence and progression of the disease can be reduced through appropriate drug treatment ...

GVSU professor, student help discover one-million-year-old monkey fossil

2015-09-04

ALLENDALE, Mich. -- An international team of scientists, including a Grand Valley State University professor and alumni, recently discovered a species of monkey fossil the team has dated to be more than one million years old.

The discovery was made after the team recovered a fossil tibia (shin bone) belonging to the species of extinct monkey Antillothrix bernensis from an underwater cave in Altagracia Province, Dominican Republic. The species was roughly the size of a small cat, dwelled in trees, and lived largely on a diet of fruits and leaves.

"We know that there ...

Polar bears may survive ice melt, with or without seals

2015-09-04

As climate change accelerates ice melt in the Arctic, polar bears may find caribou and snow geese replacing seals as an important food source, shows a recent study published in the journal PLOS ONE. The research, by Linda Gormezano and Robert Rockwell at the American Museum of Natural History, is based on new computations incorporating caloric energy from terrestrial food sources and indicates that the bears' extended stays on land may not be as grim as previously suggested.

"Polar bears are opportunists and have been documented consuming various types and combinations ...

Bring on the night, say National Park visitors in new study

2015-09-04

Natural wonders like tumbling waterfalls, jutting rock faces and banks of wildflowers have long drawn visitors to America's national parks and inspired efforts to protect their beauty.

According to a study published Sept. 4 in Park Science, visitors also value and seek to protect a different kind of threatened natural resource in the parks: dark nighttime skies.

Almost 90 percent of visitors to Maine's Acadia National Park interviewed for the study agreed or strongly agreed with the statements, "Viewing the night sky is important to me" and "The National Park Service ...

Researchers show effectiveness of non-surgical treatment of lumbar spinal stenosis

2015-09-04

(Boston)--Patients with spinal stenosis (SS) experienced good short term benefit, lasting from weeks to months, after receiving epidural steroid injections (ESI).

These findings, which appear in a letter in the journal Pain Medicine, contradict a previously published New England Journal Medicine (NEJM) study that found epidural steroid injections were not helpful in spinal stenosis cases.

It has been one year since the publication of "A Randomized Trial of Epidural Glucocorticoid Steroid Injections for Spinal Stenosis." This was a large scale clinical trial evaluating ...

The million year old monkey: New evidence confirms the antiquity of fossil primate

2015-09-04

An international team of scientists have dated a species of fossil monkey found across the Caribbean to just over 1 million years old.

The discovery was made after the researchers recovered a fossil tibia (shin bone) belonging to the species of extinct monkey Antillothrix bernensis from an underwater cave in Altagracia Province, Dominican Republic. The fossil was embedded in a limestone rock that was dated using the Uranium-series technique.

In a paper published this week in the well renowned international journal, the Journal of Human Evolution, the team use three-dimensional ...

NASA sees Tropical Storm Kevin stream high clouds over Baja California

2015-09-04

Tropical Storm Kevin's center was several hundred miles south-southwest of Baja California when NASA's Aqua satellite passed overhead and saw some associated high clouds streaming over the peninsula.

The MODIS and the AIRS instruments aboard Aqua captured visible and infrared images of Kevin on September 3 at 20:50 UTC (4:50 p.m. EDT). The visible image from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument provided look at Kevin's clouds. MODIS showed a somewhat elongated tropical storm with a fragmented band of thunderstorms wrapping into the low-level ...

Scientists unlock the secrets of a heat-loving microbe

2015-09-04

Scientists studying how a heat-loving microbe transfers its DNA from one generation to the next say it could further our understanding of an extraordinary superbug.

Sulfolobus is part of the Archaea kingdom - a single-cell organism similar to bacteria - which was isolated in hot springs on the island of Hokkaido, Japan.

Some Archaea live ordinary lives in mundane environments such as lakes, seas and insect and mammal intestinal tracts, while others live extraordinary lives pushed to extremes in incredibly harsh habitats such as deep sea hydrothermal vents, volcanic ...

Computer graphics: Less computing time for sand

2015-09-04

"Objects of granular media, such as a sandcastle, consist of millions or billions of grains. The computation time needed to produce photorealistic images amounts to hundreds to thousands of processor hours," Professor Carsten Dachsbacher of the Institute for Visualization and Data Analysis of KIT explains. Materials, such as sand, salt or sugar, consist of randomly oriented grains that are visible at a closer look only. Image synthesis, the so-called rendering, is very difficult, as the paths of millions of light rays through the grains have to be simulated. "In addition, ...