(Press-News.org) New research from the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Laboratories shows that a more acidic ocean can weaken the protective shell of a delicate alga. The findings, published Sept. 9 in the journal Biology Letters, come at a time when global climate change may increase ocean acidification.

The creature in question is Acetabularia acetabulum, commonly called the mermaid's wineglass. Reaching a height of just a few inches, this single-celled alga lives on shallow seafloors, where sunlight can still filter down for photosynthesis. Like many marine creatures, the mermaid's wineglass sports a supportive skeleton made of calcium carbonate. Its skeleton is thought to deter grazing by predators and keep the alga's thin stem rigid to support the round reproductive structure on top, said UW biology professor and senior author Emily Carrington.

Increasing acidity of ocean water disrupts calcium carbonate levels. The more acidic the water is, the less calcium carbonate is available to living organisms. No studies had shown if even a slight increase in ocean acidity could weaken the shell of the mermaid's wineglass. But three years ago a colleague told Carrington and UW biology doctoral student Laura Newcomb that the mermaid's wineglass grows differently in certain parts of the Mediterranean Sea.

"Jason Hall-Spencer from Plymouth University came to Friday Harbor to talk about his research on underwater carbon dioxide seeps in Europe," said Carrington. "He said the mermaid's wineglass looks different when it grows close to the seeps, and asked us if anyone might be interested in finding out why."

Carrington and Newcomb, who want to understand how marine organisms adapt to changing environmental conditions, were intrigued by the differences Hall-Spencer reported.

"The algae far from the seeps appeared whiter -- probably because of their well-developed skeletons," said Newcomb, who is lead author on the paper. "But ones found closer to the vents are more brown and green."

Underwater volcanic activity creates CO2 seeps, which spew gas and minerals into the water column. This includes dissolved carbon dioxide, which makes ocean waters near the vents more acidic. Newcomb wondered if mermaid's wineglass algae growing closer to the seeps had weaker calcium carbonate skeletons. She measured the composition, morphology and stiffness of preserved algae that Hall-Spencer had collected, and found that algae near the vents were thinner and droopier.

But Newcomb and Carrington worried that the preservative the algae had been stored in might have affected the measurements. There was only one thing to do.

"She needed to go to Italy to work with live algae," said Carrington. "Poor thing."

The CO2 seeps were located near Vulcano, an island off the northern coast of Sicily. Newcomb collected fresh samples of the mermaid's wineglass -- both near and far from the seeps -- and measured the carbon dioxide levels of the water at each site.

"The sites around the CO2 seeps are pretty shallow," said Newcomb. "So we could just snorkel and dive down to collect samples. We looked at three different sites -- low, medium and high carbon dioxide levels."

Carbon dioxide levels were five times higher at sites closest to the seeps. The CO2 readings indicated how acidified the water is at each site -- the more carbon dioxide, the more acidified.

The high carbon dioxide levels affected the composition and flexibility of mermaid's wineglass skeletons. Newcomb found that near seeps in high carbon dioxide conditions, mermaid's wineglass skeletons contained 32 percent less calcium carbonate. As a result, the straw-like stems were 40 percent less stiff and 40 percent droopier than their counterparts from low carbon dioxide waters.

"We saw a big loss in skeletal stiffness with even a small increase in carbon dioxide," said Carrington.

Newcomb and Carrington hypothesize that the less fortified mermaid's wineglass algae might be more susceptible to damage from ocean currents and grazing by marine animals. Their droopy posture may also make it difficult to disperse offspring. On the other hand, the thinner skeletons may transmit more sunlight to make food, and neither Newcomb nor her co-authors found snails -- a common wineglass muncher -- near the CO2 seeps.

"The beauty of these seep systems is that we can go back to these sites and test these hypotheses," said Carrington. "We can really try to see how increased flexibility affects the algae."

Carrington and Newcomb hope that field studies like these, which look at the mechanical function of the calcium carbonate skeletons and not just their composition, will help biologists and oceanographers understand how climate change could affect creatures like the mermaid's wineglass.

"Calcium carbonate skeletons are quite widespread in marine life, found in algae and plankton and even in larger creatures like snails and corals," said Newcomb. "And in a more acidified ocean, some creatures are able to cope and do just fine. Some, like the mermaid's wineglass here, suffer but still persist. Others will really struggle."

As human activity pumps more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, the oceans are absorbing a greater share than they have for millennia, and ocean acidification overall is expected to increase. These conditions may just bend the mermaid's wineglass, but they could break others.

INFORMATION:

Newcomb, Carrington and Hall-Spencer were joined on the paper by co-author Marco Milazzo from the University of Palermo. This study was funded by the National Science Foundation (EF-1041213) and the Mediterranean Sea Acidification Program.

For more information, contact Carrington at 201-221-4676 or ecarring@uw.edu and Newcomb at the same phone number or newcombl@uw.edu.

UC San Francisco has received a National Cancer Institute grant of $5 million over the next five years to lead a massive effort to integrate the data from all experimental models across all types of cancer. The web-based repository is an important step in moving the fight against cancer toward precision medicine.

The goal is to accelerate cancer research to improve the way we diagnose, treat and conduct further research on the disease. The resulting database, called the Oncology Models Forum (OMF), will be accessible to researchers through the National Institutes of ...

Current drugs may stop working against the most common type of brain tumor in children, medulloblastoma, but the tumor could be targeted in a new way, according to Stanford University scientists.

In research to be published in the journal eLife, a team led by Prof. Matthew P. Scott at the University's School of Medicine tested a drug called Roflumilast in mice with a brain tumor that is resistant to Vismodegib, the drug in current use. Roflumilast is normally used to treat inflammatory lung diseases. It dramatically inhibited tumor growth from the first day of treatment. ...

This news release is available in French.

Montreal, September 15th 2015 - It is estimated that half of all cancer patients suffer from a muscle wasting syndrome called cachexia. Cancer cachexia impairs quality of life and response to therapy, which increases morbidity and mortality of cancer patients. Currently, there is no approved treatment for muscle wasting but a new study from the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) and University of Alberta could be a game changer for patients, improving both quality of life and longevity. The ...

To better inform the tradeoffs involved in land use choices around the world, experts have assessed the value of ecosystem services provided by land resources such as food, poverty reduction, clean water, climate and disease regulation and nutrients cycling.

Their report today estimates the value of ecosystem services worldwide forfeited due to land degradation at a staggering US $6.3 trillion to $10.6 trillion annually, or the equivalent of 10-17% of global GDP.

Furthermore, the problem threatens to force the migration of millions of people from affected areas. ...

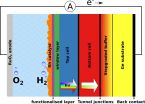

Solar energy is abundantly available globally, but unfortunately not constantly and not everywhere. One especially interesting solution for storing this energy is artificial photosynthesis. This is what every leaf can do, namely converting sunlight to chemical energy. That can take place with artificial systems based on semiconductors as well. These use the electrical power that sunlight creates in individual semiconductor components to split water into oxygen and hydrogen. Hydrogen possesses very high energy density, can be employed in many ways and could replace fossil ...

Amsterdam, NL, September 9, 2015 - The potential benefits of dietary cocoa extract and/or its final product in the form of chocolate have been extensively investigated in regard to several aspects of human health. Cocoa extracts contain polyphenols, which are micronutrients that have many health benefits, including reducing age-related cognitive dysfunction and promoting healthy brain aging, among others.

Dr. Giulio Maria Pasinetti, MD, PhD, Saunders Family Chair and Professor of Neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Director of Biomedical Training ...

OAK BROOK, Ill. - Imaging patients soon after traumatic brain injury (TBI) occurs can lead to better (more accurate) detection of cerebral microhemorrhages, or microbleeding on the brain, according to a study of military service members, published online in the journal Radiology.

Cerebral microhemorrhages occur as a direct result of TBI and can lead to severe secondary injuries such as brain swelling or stroke. The ability to monitor the evolution of microhemorrhages could provide important information regarding disease progression or recovery.

According to the Centers ...

CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA (SEPTEMBER 15, 2015). Management of Myelomeningocele Study (MOMS) investigators analyzed updated data on the effects of prenatal myelomeningocele closure on the need for placement of a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt within the first 12 months of life. These researchers reaffirm the initial MOMS finding that prenatal repair of a myelomeningocele results in less need for a shunt at 12 months and introduce the new finding that prenatal repair reduces the need for shunt revision in those infants who do require shunt placement. The researchers also found ...

In what is believed to be the largest, most detailed study of its kind in the United States, scientists at NYU Langone Medical Center and elsewhere have confirmed that tiny chemical particles in the air we breathe are linked to an overall increase in risk of death.

The researchers say this kind of air pollution involves particles so small they are invisible to the human eye (at less than one ten-thousandth of an inch in diameter, or no more than 2.5 micrometers across).

In a report on the findings, published in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives online Sept. ...

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, September 15, 2015 -- Prolonged sitting time as well as reduced physical activity contribute to the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in a study of middle-aged Koreans. These findings support the importance of both reducing time spent sitting and increasing physical activity, say researchers. Their results are published in the Journal of Hepatology.

Physical activity is known to reduce the incidence and mortality of various chronic diseases. However, more than one half of the average person's waking day involves sedentary ...