Protein that can be toxic in the heart and nerves may help prevent Alzheimer's

2021-01-07

(Press-News.org) DALLAS - Jan. 7, 2020 - A protein that wreaks havoc in the nerves and heart when it clumps together can prevent the formation of toxic protein clumps associated with Alzheimer's disease, a new study led by a UT Southwestern researcher shows. The findings, published recently in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, could lead to new treatments for this brain-ravaging condition, which currently has no truly effective therapies and no cure.

Researchers have long known that sticky plaques of a protein known as amyloid beta are a hallmark of Alzheimer's and are toxic to brain cells. As early as the mid-1990s, other proteins were discovered in these plaques as well.

One of these, a protein known as transthyretin (TTR), seemed to play a protective role, explains Lorena Saelices, Ph.D., assistant professor of biophysics and in the Center for Alzheimer's and Neurodegenerative Diseases at UTSW, a center that is part of the Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute. When mice modeled to have Alzheimer's disease were genetically altered to make more TTR, they were slower to develop an Alzheimer's-like condition; similarly, when they made less TTR, they developed the condition faster.

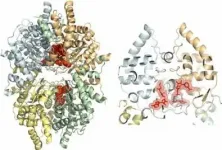

In healthy people and animals, Saelices adds, TTR helps transport thyroid hormone and the vitamin A derivative retinol to where they're needed in the body. For this job, TTR forms a tetramer - a shape akin to a clover with four identical leaflets. However, when it separates into molecules called monomers, these individual pieces can act like amyloid beta, forming sticky fibrils that join together into toxic clumps in the heart and nerves to cause the rare disease amyloidosis. In this condition, amyloid protein builds up in organs and interferes with their function.

Saelices wondered whether there might be a connection between TTR's separate roles in both preventing and causing amyloid-related diseases. "It seemed like such a coincidence that TTR had such opposing functions," she says. "How could it be both protective and damaging?"

To explore this question, she and her colleagues developed nine different TTR variants with differing propensities to separate into monomers that aggregate, forming sticky fibrils. Some did this quickly, over the course of hours, while others were slow. Still others were extremely stable and didn't dissociate into monomers at all.

When the researchers mixed these TTR variants with amyloid beta and placed them on neuronal cells, they found stark differences in how toxic the amyloid beta remained. The variants that separated into monomers and aggregated quickly into fibrils provided some protection from amyloid beta, but it was short-lived. Those that separated into monomers but took longer to aggregate provided significantly longer protection. And those that never separated provided no protection from amyloid beta at all.

Saelices and her colleagues suspected that part of TTR was binding to amyloid beta, preventing amyloid beta from forming its own aggregations. However, that important piece of TTR seemed to be hidden when this protein was in its tetramer form. Sure enough, computational studies showed a piece of this protein that was concealed when the leaflets were conjoined could stick to amyloid beta. However, this piece tended to stick to itself to quickly form clumps. After modifying this piece with chemical tags to halt self-association, the researchers created peptides that could prevent the formation of toxic amyloid beta clumps in solution and even break apart preformed amyloid beta plaques. The interaction of modified TTR peptides with amyloid beta resulted in the conversion to forms called amorphous aggregates that were easily broken up by enzymes. In addition, the modified peptides prevented amyloid "seeding," a process in which fibrils of amyloid beta extracted from Alzheimer's disease patients can template the formation of new fibrils.

Saelices and her colleagues are currently testing whether this modified TTR peptide can prevent or slow progression of Alzheimer's in mouse models. If they're successful, she says, this protein snippet could form the basis of a new treatment for this recalcitrant condition.

"By solving the mystery of TTR's dual roles," she says, "we may be able to offer hope to patients with Alzheimer's."

INFORMATION:

Other researchers who contributed to this study include Qin Cao, Daniel H. Anderson, Wilson Y. Liang, and Joshua Chou, all of the University of California, Los Angeles.

This work was supported by Amyloidosis Foundation grants 20160759 and 20170827 and the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under Research Executive Agency (REA) Grant Agreement 298559.

About UT Southwestern Medical Center

UT Southwestern, one of the premier academic medical centers in the nation, integrates pioneering biomedical research with exceptional clinical care and education. The institution's faculty has received six Nobel Prizes, and includes 23 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 17 members of the National Academy of Medicine, and 13 Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigators. The full-time faculty of more than 2,500 is responsible for groundbreaking medical advances and is committed to translating science-driven research quickly to new clinical treatments. UT Southwestern physicians provide care in about 80 specialties to more than 105,000 hospitalized patients, nearly 370,000 emergency room cases, and oversee approximately 3 million outpatient visits a year.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-07

Brazilian researchers have managed to decipher the structure of a protein found in parasites that cause neglected tropical diseases, paving the way to the development of novel medications. Thanks to the discovery it will be possible to seek more potent molecules capable of destroying the pathogens directly, with fewer adverse side-effects for patients.

The study detailed the structural characteristics of the protein deoxyhypusine synthase (DHS), found in Brugia malayi, one of the mosquito-borne parasites that cause elephantiasis, and in Leishmania major, the protozoan that causes cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Elephantiasis, also known as lymphatic filariasis, is an infection of the lymph system that can lead to swelling of the legs, arms, and genitalia. It may also harden and ...

2021-01-07

HOUSTON - (Jan. 7, 2021) - Proteogenomic analysis may offer new insight into matching cancer patients with an effective therapy for their particular cancer. A new study identifies three molecular subtypes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) that could be used to better determine appropriate treatment. The research led by Baylor College of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University and the National Cancer Institute's Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) is published in the journal Cancer Cell.

Researchers profiled proteins, phosphosites and signaling ...

2021-01-07

TROY, N.Y. -- In a money-saving revelation for organizations inclined to invest in specialized information technology to support the process of idea generation, new research suggests that even non-specialized, everyday organizational IT can encourage employees' creativity.

Recently published in the journal Information and Organization, these findings from Dorit Nevo, an associate professor in the Lally School of Management at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, show standard IT can be used for innovation. Furthermore, this is much more likely to happen when the technology is in the hands of employees who are motivated to master technology, understand their role in the organization, ...

2021-01-07

In a study to examine a Mediterranean diet in relation to prostate cancer progression in men on active surveillance, researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center found that men with localized prostate cancer who reported a baseline dietary pattern that more closely follows the key principles of a Mediterranean-style diet fared better over the course of their disease.

"Men with prostate cancer are motivated to find a way to impact the advancement of their disease and improve their quality of life," said Justin Gregg, M.D., assistant professor of Urology and lead author of the study, published today in Cancer. ...

2021-01-07

Tsukuba, Japan - Does losing weight while you sleep sound too good to be true? According to a study by the University of Tsukuba, it seems that drinking oolong tea might help you do just that.

While all tea comes from the same plant, Camellia sinensis, the degree of oxidation, a chemical reaction that turns tea leaves black, defines its specific type. For example, green tea is unoxidized and mild in flavor, while the distinctive color of black tea comes from complete oxidation. Oolong tea, being only partially oxidized, lies somewhere in between and displays characteristics ...

2021-01-07

Some people have lost their eyesight, but they continue to "see." This phenomenon, a kind of vivid visual hallucination, is named after the Swiss doctor, Charles Bonnet, who described in 1769 how his completely blind grandfather experienced vivid, detailed visions of people, animals and objects. Charles Bonnet syndrome, which appears in those who have lost their eyesight, was investigated in a study led by scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science. The findings, published today in Brain, suggest a mechanism by which normal, spontaneous activity in the visual centers of the brain can trigger visual hallucinations in the blind.

Prof. Rafi Malach and his group members of the Institute's Neurobiology Department research the phenomenon of spontaneous "resting-state" ...

2021-01-07

Research from life-saving charity Air Ambulance Kent Surrey Sussex (KSS) in partnership with the University of Surrey has shown the benefits of dispatching HEMS to patients with a sudden, unexplained LOC of medical origin and a high prevalence of acute neurological pathology.

The study - which is believed to be the first published about HEMS dispatch to non-trauma (neuro) cases - also highlights how HEMS dispatchers in dialogue with ambulance personnel are able to select patients requiring HEMS-specific interventions and, based on its findings, identifies opportunities to improve triage for these patients.

Through a retrospective study of all patients with a LOC ...

2021-01-07

In a study spanning four decades, researchers from the University of Hong Kong's Research Division for Ecology & Biodiversity (HKU) in the Faculty of Science, and Toho University's Department of Biology (Toho), Japan, have discovered that predation by snakes is pushing lizards to be active at warmer body temperatures on islands where snakes are present, in comparison to islands free from snakes. Their work also detected significant climatic warming throughout the years and found lizard body temperatures to have also increased accordingly. The findings show that lizard thermal biology is highly dependent on predation pressures ...

2021-01-07

Geneva, Switzerland, 7 January 2021 - 'Mini-brains' are pin-head sized collections of several different types of human brain cell. They are used as a tool, allowing scientists to learn about how the brain develops, study disease and test new medicines. Personalized 'mini-brains' can be grown from stem cells generated from a sample of human hair or skin and could shed light on how brain disease progresses in an individual and how this person may respond to drugs.

Research published today by a team of scientists and engineers from HEPIA and the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, in the journal Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, has revealed ...

2021-01-07

Until now, the reason why the drug levodopa (L-Dopa), which reduces the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease, declines in efficacy after a few years' use has been unknown. A side effect that then often occur is involuntary movements. A Swedish-French collaboration, led from Uppsala University, has now been able to connect the problems with defective metabolism of L-Dopa in the brain. The study is published in Science Advances.

"The findings may lead to new strategies for treating advanced Parkinson's," says Professor Per Andrén of the Department of Pharmaceutical Biosciences at Uppsala University. He and Dr Erwan Bézard of the University of Bordeaux, France, headed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Protein that can be toxic in the heart and nerves may help prevent Alzheimer's