Research shows rising lizard temperatures may change predator-prey relationship with snakes

Four decades of research on Japanese Izu Islands finds rising lizard temperatures may change predator-prey relationship with snakes

2021-01-07

(Press-News.org) In a study spanning four decades, researchers from the University of Hong Kong's Research Division for Ecology & Biodiversity (HKU) in the Faculty of Science, and Toho University's Department of Biology (Toho), Japan, have discovered that predation by snakes is pushing lizards to be active at warmer body temperatures on islands where snakes are present, in comparison to islands free from snakes. Their work also detected significant climatic warming throughout the years and found lizard body temperatures to have also increased accordingly. The findings show that lizard thermal biology is highly dependent on predation pressures and that body temperatures are rising suggest that such ectothermic predator-prey relationships may be changing under climatic warming.

Lizard VS Snakes on Izu Islands

The research published in the journal Ecology Letters is the first to present long-term observations on the thermal biology behind the prey-predator relationship of snakes and lizards on the Izu Islands. Less than a million years old, these islands are located near the southeastern coast of the Japanese mainland and represent a valuable natural laboratory for studying ecological and evolutionary processes. Similar to the reasons initially drawing evolutionary biologists to the Galapagos, the simplified island system with low numbers of species overall provides an opportunity to directly study selective pressures on species.

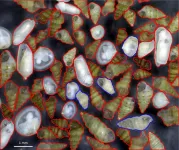

In this system, one dominant lizard species is found on all these islands; Okada's five-lined skink (Plestiodon latiscutatus). Its mainland predator, the Japanese four-lined rat snake (Elaphe quadrivirgata), is found on most but not all of the islands. This has resulted P. latiscutatus populations that have experienced different evolutionary pressures, either free from or subject to predation by E. quadrivirgata.

The research was conducted by PhD student Félix LANDRY YUAN (HKU) and PhD Candidate Shun ITO (Tohoku University's Graduate School of Life Science) and led by Dr Timothy BONEBRAKE (HKU) and Professor Masami HASEGAWA (Toho). Initial observation and data collection was first started by Professor HASEGAWA in the early 1980's, when he first noticed lizard behaviour differed on islands with and without snakes. Professor Hasegawa has since continually visited the islands annually to catch lizards and snakes for body temperature and morphological measurements. The researchers have accordingly detected that annual temperatures across the Izu Islands had increased by just over 1°C since Professor Hasegawa first started his observations, and that lizard body temperature had also increased with the same magnitude.

Higher body temperature helps the lizards

In addition to body temperature measurements, in 2018 and 2019 Félix Landry Yuan carried a portable racetrack, tripod and camera to the islands to measure the speed at which lizards ran at different temperatures. By analyzing thermally dependent running speeds of over 150 lizards across the islands, the researchers were able to establish how predation by snakes affected lizard thermal biology and the probable consequences for their fitness. Dr Bonebrake notes that: "by racing lizards of different temperatures down a track, Félix was able to show that optimal temperatures were higher for lizards on the island with snakes, consistent with the high body temperatures observed on the island. Shun Ito was also able to identify differences in lizard hind leg length that had consequences for survival. Thus, the higher body temperatures and morphological differences help the lizards run faster and better escape the snakes. The exciting and unique aspect of this work is how the experimental work matches and supports the extensive natural history data and observation."

With climate change ongoing, the dynamics of this prey-predator relationship could be affected on islands with snakes, as lizard body temperatures are likely to continue to rise. In addition, as predation has considerable consequences for the thermal biology of its prey, the presence or absence of snake predators could differentially influence general vulnerability of lizards to climatic warming across islands.

The Izu Islands demonstrate the value of island systems in teasing apart mechanisms through which predation directly influences behaviour, morphology and physiology of prey species. On the other hand, understanding the ways in which predation can affect prey responses to climate change requires long-term study. This international collaboration between HKU and Toho used these unique properties of this system (and Professor Hasegawa's forethought and intensive data collections since the 80s) to show how predator-prey relationships may be vulnerable in a warming climate. "It is a great pleasure to reveal ecological and evolutionary responses among prey and predator interactions by this international research team. I'm very hopeful that the Izu islands become a key model island system to study ongoing evolution under global environmental change by attracting ambitious young Asian biologists to research this further." Professor HASEGAWA said.

INFORMATION:

Félix Landry Yuan was supported by a Hong Kong PhD Fellowship from the Research Grants Council. Professor Masami Hasegawa received funding for this work from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) - (19H03307, 15H04426).

About the research paper "Predator presence and recent climatic warming raise body temperatures of island lizards": https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ele.13671

Landry Yuan F*, Ito S*, Tsang TPN, Kuriyama T, Yamakazi T, Bonebrake TC, Hasegawa M (2021) Ecology Letters *These authors contributed equally to the manuscript.

Images download and captions: https://www.scifac.hku.hk/press

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-07

Geneva, Switzerland, 7 January 2021 - 'Mini-brains' are pin-head sized collections of several different types of human brain cell. They are used as a tool, allowing scientists to learn about how the brain develops, study disease and test new medicines. Personalized 'mini-brains' can be grown from stem cells generated from a sample of human hair or skin and could shed light on how brain disease progresses in an individual and how this person may respond to drugs.

Research published today by a team of scientists and engineers from HEPIA and the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, in the journal Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, has revealed ...

2021-01-07

Until now, the reason why the drug levodopa (L-Dopa), which reduces the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease, declines in efficacy after a few years' use has been unknown. A side effect that then often occur is involuntary movements. A Swedish-French collaboration, led from Uppsala University, has now been able to connect the problems with defective metabolism of L-Dopa in the brain. The study is published in Science Advances.

"The findings may lead to new strategies for treating advanced Parkinson's," says Professor Per Andrén of the Department of Pharmaceutical Biosciences at Uppsala University. He and Dr Erwan Bézard of the University of Bordeaux, France, headed ...

2021-01-07

The coastline of Israel is one of the warmest areas in the Mediterranean Sea. Here, most marine species have been at the limits of their tolerance to high temperatures for a long time - and now they are already beyond those limits. Global warming has led to an increase in sea temperatures beyond those temperatures that Mediterranean species can sustain. Consequently, many of them are going locally extinct.

Paolo Albano's team quantified this local extinction for marine molluscs, an invertebrate group encompassing snails, clams and mussels. They thoroughly surveyed the Israeli coastline and ...

2021-01-07

Sweden kept preschools, primary and lower secondary schools open during the spring of 2020. So far, little research has been done on the risk of children being seriously affected by COVID-19 when the schools were open. A study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden has now shown that one child in 130,000 was treated in an intensive care unit on account of COVID-19 during March-June. The study has been published in New England Journal of Medicine.

So far, more than 80 million people have become ill with COVID-19 and globally, almost two million people have died from the disease. Many countries have closed down parts of society in order to reduce the spread of infection. One such measure has been to close schools. ...

2021-01-07

Men and women aged over 50 can reap similar relative benefits from resistance training, a new study led by UNSW Sydney shows.

While men are likely to gain more absolute muscle size, the gains relative to body size are on par to women's.

The findings, recently published in END ...

2021-01-07

Social media misinformation can negatively influence people's attitudes about vaccine safety and effectiveness, but credible organizations -- such as research universities and health institutions -- can play a pivotal role in debunking myths with simple tags that link to factual information, University of California, Davis, researchers, suggest in a new study.

Researchers found that fact-check tags located immediately below or near a post can generate more positive attitudes toward vaccines than misinformation alone, and perceived source expertise makes a difference.

"In fact, fact-checking labels ...

2021-01-07

An international team of researchers led by Swinburne University of Technology has demonstrated the world's fastest and most powerful optical neuromorphic processor for artificial intelligence (AI), which operates faster than 10 trillion operations per second (TeraOPs/s) and is capable of processing ultra-large scale data.

Published in the prestigious journal Nature, this breakthrough represents an enormous leap forward for neural networks and neuromorphic processing in general.

Artificial neural networks, a key form of AI, can 'learn' and perform complex operations with wide applications to computer vision, natural language processing, facial recognition, speech translation, ...

2021-01-07

El Niño events have long been perceived as a driver for low rainfall in the winter and spring in Hawai'i, creating a six-month wet-season drought. However, a recent study by researchers in the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) revealed the connection between Hawai'i winter rainfall and El Niño is not as straightforward as previously thought.

Studies in the past decade suggested that there are at least two types of El Niño: the Eastern Pacific and Central Pacific, when the warmest pool of water is located in the eastern or central portions of the ocean basin, respectively. El Niño events usually ...

2021-01-07

WASHINGTON--Black and Hispanic people with COVID-19 and diabetes are more likely than Caucasians to die or have serious complications, according to a new study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. ...

2021-01-07

With an estimated lifespan between 25 to 40 years, the queen conch (Strombus gigas) is a prized delicacy long harvested for food and is revered for its beautiful shell. Second only to the spiny lobster, it is one of the most important benthic fisheries in the Caribbean region. Unfortunately, the species faces a challenge of survival: how to endure and thrive, as populations are in a steady state of decline from overfishing, habitat degradation and hurricane damage. In some places, the conch populations have dwindled so low that the remaining conch cannot find breeding partners. This dire situation is urgent in ecological and economic terms.

To preserve this most significant molluscan fishery in the Caribbean, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Research shows rising lizard temperatures may change predator-prey relationship with snakes

Four decades of research on Japanese Izu Islands finds rising lizard temperatures may change predator-prey relationship with snakes