(Press-News.org) Some people have lost their eyesight, but they continue to "see." This phenomenon, a kind of vivid visual hallucination, is named after the Swiss doctor, Charles Bonnet, who described in 1769 how his completely blind grandfather experienced vivid, detailed visions of people, animals and objects. Charles Bonnet syndrome, which appears in those who have lost their eyesight, was investigated in a study led by scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science. The findings, published today in Brain, suggest a mechanism by which normal, spontaneous activity in the visual centers of the brain can trigger visual hallucinations in the blind.

Prof. Rafi Malach and his group members of the Institute's Neurobiology Department research the phenomenon of spontaneous "resting-state" fluctuations in the brain. These mysterious slow fluctuations, which occur all over the brain, take place well below the threshold of consciousness. Despite a fair amount of research into these spontaneous fluctuations, their function is still largely unknown. The research group hypothesized that these fluctuations underlie spontaneous behaviors. However, it is typically difficult to investigate truly unprompted behaviors in a scientific manner for two reasons, since, for one, instructing people to behave spontaneously is usually a spontaneity-killer. Secondly, it is difficult to separate the brain's spontaneous fluctuations from other, task-related brain activity. The question was: How could they isolate a case of a truly spontaneous, unprompted, behavior in which the role of spontaneous brain activity could be tested?

Individuals experiencing Charles Bonnet visual hallucinations presented the group with a rare opportunity to investigate their hypothesis. This is because in Charles Bonnet syndrome, the hallucinations appear at random, in a truly unprompted fashion, and the visual centers of the brain do not process outside stimuli (because these individuals are blind), and are thus activated spontaneously. In a study led by Dr. Avital Hahamy, a former research student in Malach's lab who is now a postdoctoral research fellow at University College London, the relation between these hallucinations and the spontaneous brain activity has indeed been unveiled.

The researchers first invited to their lab five people who had lost their sight and reported occasionally experiencing clear visual hallucinations. These participants' brain activity was measured using an fMRI scanner while they described their hallucinations as these occurred. The scientists then created movies based on the participants' verbal descriptions, and they showed these movies to a sighted control group, also inside the fMRI scanner. A second control group consisted of blind people who had lost their sight but did not experience visual hallucinations. These were asked to imagine similar visual images while in the scanner.

The same visual areas in the brain were active in all three groups - those that hallucinated, those that watched the films and those creating imagery in their minds' eye. But the researchers noted a difference in the timing of the neural activity between these groups. In both the sighted participants and those in the imagery group, the activity was seen to take place in response either to visual input or to the instructions set in the task. But in the group with Charles Bonnet syndrome, the scientists observed a gradually increasing wave of activity, reminiscent of the slow spontaneous fluctuations, that emerged just before the onset of the hallucinations. In other words, the hallucinations were not the result of external stimuli (eg., sensory images or instructions to imagine specific things), but were rather evoked internally by the slow, spontaneous, brain activity fluctuations.

"Our research clearly shows that the same visual system is active when we see the world outside of us, when we imagine it, when we hallucinate, and probably also when we dream," says Malach. "It also exemplifies the creative power of vision and the contribution of spontaneous brain activity to unprompted and creative behaviors," he adds.

In addition to the scientific value of the work, Hahamy hopes it may raise awareness of Charles Bonnet syndrome, which can be frightening to those who experience it. "These individuals may keep their visual hallucinations a secret - even from doctors and family - and we want them to understand that these visions are a natural product of a healthy brain, in which the visual centers remain intact, even if the eyes have ceased to send them sensory input," she says.

INFORMATION:

Also participating in this research were Dr. Meytal Wilf, formerly in Malach's lab, of Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland; Dr. Boris Rosin, of the Ophthalmology Departments of Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, and University of of Pittsburgh Medical Center; and Prof. Marlene Behrmann of Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Prof. Rafael Malach's research is supported by the Dr. Lou Siminovitch Laboratory for Research in Neurobiology.

The Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, is one of the world's top-ranking multidisciplinary research institutions. Noted for its wide-ranging exploration of the natural and exact sciences, the Institute is home to scientists, students, technicians and supporting staff. Institute research efforts include the search for new ways of fighting disease and hunger, examining leading questions in mathematics and computer science, probing the physics of matter and the universe, creating novel materials and developing new strategies for protecting the environment.

Research from life-saving charity Air Ambulance Kent Surrey Sussex (KSS) in partnership with the University of Surrey has shown the benefits of dispatching HEMS to patients with a sudden, unexplained LOC of medical origin and a high prevalence of acute neurological pathology.

The study - which is believed to be the first published about HEMS dispatch to non-trauma (neuro) cases - also highlights how HEMS dispatchers in dialogue with ambulance personnel are able to select patients requiring HEMS-specific interventions and, based on its findings, identifies opportunities to improve triage for these patients.

Through a retrospective study of all patients with a LOC ...

In a study spanning four decades, researchers from the University of Hong Kong's Research Division for Ecology & Biodiversity (HKU) in the Faculty of Science, and Toho University's Department of Biology (Toho), Japan, have discovered that predation by snakes is pushing lizards to be active at warmer body temperatures on islands where snakes are present, in comparison to islands free from snakes. Their work also detected significant climatic warming throughout the years and found lizard body temperatures to have also increased accordingly. The findings show that lizard thermal biology is highly dependent on predation pressures ...

Geneva, Switzerland, 7 January 2021 - 'Mini-brains' are pin-head sized collections of several different types of human brain cell. They are used as a tool, allowing scientists to learn about how the brain develops, study disease and test new medicines. Personalized 'mini-brains' can be grown from stem cells generated from a sample of human hair or skin and could shed light on how brain disease progresses in an individual and how this person may respond to drugs.

Research published today by a team of scientists and engineers from HEPIA and the Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, in the journal Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, has revealed ...

Until now, the reason why the drug levodopa (L-Dopa), which reduces the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease, declines in efficacy after a few years' use has been unknown. A side effect that then often occur is involuntary movements. A Swedish-French collaboration, led from Uppsala University, has now been able to connect the problems with defective metabolism of L-Dopa in the brain. The study is published in Science Advances.

"The findings may lead to new strategies for treating advanced Parkinson's," says Professor Per Andrén of the Department of Pharmaceutical Biosciences at Uppsala University. He and Dr Erwan Bézard of the University of Bordeaux, France, headed ...

The coastline of Israel is one of the warmest areas in the Mediterranean Sea. Here, most marine species have been at the limits of their tolerance to high temperatures for a long time - and now they are already beyond those limits. Global warming has led to an increase in sea temperatures beyond those temperatures that Mediterranean species can sustain. Consequently, many of them are going locally extinct.

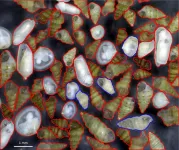

Paolo Albano's team quantified this local extinction for marine molluscs, an invertebrate group encompassing snails, clams and mussels. They thoroughly surveyed the Israeli coastline and ...

Sweden kept preschools, primary and lower secondary schools open during the spring of 2020. So far, little research has been done on the risk of children being seriously affected by COVID-19 when the schools were open. A study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden has now shown that one child in 130,000 was treated in an intensive care unit on account of COVID-19 during March-June. The study has been published in New England Journal of Medicine.

So far, more than 80 million people have become ill with COVID-19 and globally, almost two million people have died from the disease. Many countries have closed down parts of society in order to reduce the spread of infection. One such measure has been to close schools. ...

Men and women aged over 50 can reap similar relative benefits from resistance training, a new study led by UNSW Sydney shows.

While men are likely to gain more absolute muscle size, the gains relative to body size are on par to women's.

The findings, recently published in END ...

Social media misinformation can negatively influence people's attitudes about vaccine safety and effectiveness, but credible organizations -- such as research universities and health institutions -- can play a pivotal role in debunking myths with simple tags that link to factual information, University of California, Davis, researchers, suggest in a new study.

Researchers found that fact-check tags located immediately below or near a post can generate more positive attitudes toward vaccines than misinformation alone, and perceived source expertise makes a difference.

"In fact, fact-checking labels ...

An international team of researchers led by Swinburne University of Technology has demonstrated the world's fastest and most powerful optical neuromorphic processor for artificial intelligence (AI), which operates faster than 10 trillion operations per second (TeraOPs/s) and is capable of processing ultra-large scale data.

Published in the prestigious journal Nature, this breakthrough represents an enormous leap forward for neural networks and neuromorphic processing in general.

Artificial neural networks, a key form of AI, can 'learn' and perform complex operations with wide applications to computer vision, natural language processing, facial recognition, speech translation, ...

El Niño events have long been perceived as a driver for low rainfall in the winter and spring in Hawai'i, creating a six-month wet-season drought. However, a recent study by researchers in the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST) revealed the connection between Hawai'i winter rainfall and El Niño is not as straightforward as previously thought.

Studies in the past decade suggested that there are at least two types of El Niño: the Eastern Pacific and Central Pacific, when the warmest pool of water is located in the eastern or central portions of the ocean basin, respectively. El Niño events usually ...