(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA - Medical school curriculums may misuse race and play a role in perpetuating physician bias, a team led by Penn Medicine researchers found in an analysis of curriculum from the preclinical phase of medical education. In a perspective piece published Tuesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers identified five key categories in which curriculum misrepresented race in class discussions, presentations, and assessments. The authors recommend that rather than oversimplifying conversations about how race affects diseases' prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment, medical school faculty must widen the lens to "impart an adequate and accurate understanding of the complexity of these relationships."

"In medical school, 20 years ago, we often learned that higher rates of hypertension in certain racial and ethnic groups, was due to genetic predisposition, personal behaviors, or unfortunate circumstances. Now we know this is not true. There are no characteristics innate to racial and ethnic groups, biological or otherwise, that adequately explains these differences. They stem, instead, from differential experiences in our society -- it's structural racism, not race," said the study's senior author Jaya Aysola, MD, MPH, assistant dean of Inclusion and Diversity in the Perelman School of Medicine and executive director at the Penn Medicine Center for Health Equity Advancement. "When we speak of dismantling structural racism, we must begin with medical education, where these sorts of race-based biases are still being reinforced in the classroom."

Though the researchers focused on lectures from a single medical school, the study authors from other institutions found similar misrepresentations of race in their preclinical medical curriculums. The five categories of biases that the research team identified were: semantics, prevalence of disparities without context, race-based diagnostic bias, pathologizing race, and race-based clinical guidelines.

For example, the study authors noted the use of "African American," is a socially and politically meaningful identity for many people, but not for all people of African descent. Moreover, they write, it is a poor proxy for genetic difference, since it lumps people from many different ancestral populations together. The researchers also found that students were taught about the disproportionate burden of type 2 diabetes among the U.S. Akimel O'odham (formerly known as Pima) people, without sufficient historical and social context. Despite high degrees of genetic similarity, the Akimel O'odham living in Mexico have significantly lower rates of diabetes and obesity than those living in the U.S. The authors explain that a the construction of the Hoover Dam in 1930 that pushed the Akimel O'odham from their lands and into poverty, not a genetic predisposition, explains this pattern. The researchers also highlighted the teaching of guidelines that endorse the use of racial categories in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases. One course they analyzed, for instance, encouraged the use of race-adjusted glomerular filtration rate, or GFR, equations, which many experts now say limits care for Black patients and exacerbates health disparities.

"Race is not a biomedical term, and it is a poor proxy for ancestry. Yet, we continue to generate, impart, and assess medical knowledge with this imprecision. In doing so, we perpetuate biases and ignore the actual contributors to the race-based differences we see," Aysola said. "There are several aspects of the medical education apparatus that we have to fundamentally change in order to get to the ideal state where we're dismantling the structures that perpetuate racism."

The authors recommend that medical schools:

Standardize language to describe race and ethnicity, such as using a country of origin to discuss genetic predisposition to disease, rather than "Asian" or "African American."

Appropriately contextualize racial and ethnic differences in disease burden, including always considering the structural and social determinants of disease.

Generate and impart evidence-based medical knowledge when it comes to race, such as reforming board examinations to avoid testing students on race-based clinical guidelines and racial heuristics.

"We are not arguing that race is irrelevant, and our framework is not meant to trigger discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of using race in medicine," the authors write in closing. "Rather, we wish to provide evidence-based guidelines for defining and using race in generating and imparting medical knowledge."

INFORMATION:

Penn authors Christina Amutah, Kaliya Greenidge, Adjoa Mante, Michelle Munyikwa, Sanjna L. Surya, Eve Higginbotham, Dorothy Roberts, and Risa Lavizzo-Mourey also contributed to this work.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

In what is believed to be the most comprehensive molecular characterization to date of the most common type of head and neck cancer, researchers from the Johns Hopkins departments of END ...

As the planet continues to warm, the twin challenges of diminishing water supply and growing energy demand will intensify. But water and energy are inextricably linked. For instance, nearly a fifth of California's energy goes toward water-related activities, while more than a tenth of the state's electricity comes from hydropower. As society tries to adapt to one challenge, it needs to ensure it doesn't worsen the other.

To this end, researchers from UC Santa Barbara, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and UC Berkeley have developed a framework to evaluate how different climate adaptations may impact this water-energy nexus. Their research appears in the open access journal Environmental Research Letters.

"Electricity and water systems are linked in many ...

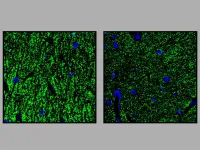

Impaired intelligence, movement disorders and developmental delays are typical for a group of rare diseases that belong to GPI anchor deficiencies. Researchers from the University of Bonn and the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics used genetic engineering methods to create a mouse that mimics these patients very well. Studies in this animal model suggest that in GPI anchor deficiencies, a gene mutation impairs the transmission of stimuli at the synapses in the brain. This may explain the impairments associated with the disease. The results are now published ...

INDIANAPOLIS-- Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center published promising findings today in the New England Journal of Medicine on preventing a common complication to lifesaving blood stem cell transplantation in leukemia.

Sherif Farag, MD, PhD, found that using a drug approved for Type 2 diabetes reduces the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), one of the most serious complications of blood stem cell transplantation. GVHD occurs in more than 30 percent of patients and can lead to severe side effects and potentially fatal results. Farag is ...

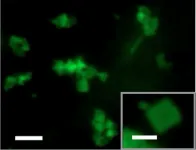

Chemists have developed a nanomaterial that they can trigger to shape shift -- from flat sheets to tubes and back to sheets again -- in a controllable fashion. The Journal of the American Chemical Society published a description of the nanomaterial, which was developed at Emory University and holds potential for a range of biomedical applications, from controlled-release drug delivery to tissue engineering.

The nanomaterial, which in sheet form is 10,000 times thinner than the width of a human hair, is made of synthetic collagen. Naturally occurring collagen is the most abundant protein in humans, making the new material intrinsically biocompatible.

"No one has previously made collagen ...

Alexandria, Va., USA -- The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted dental education and training. The study "COVID-19 and Dental and Dental Hygiene Students' Career Plans," published in the JDR Clinical & Translational Research (JDR CTR), examined the short-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental hygiene and dental students' career intentions.

An anonymous online survey was emailed to dental and dental hygiene students enrolled at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Dentistry, Richmond, USA. The survey consisted of 81 questions that covered a wide range of topics including demographics, anticipated educational debt, career plans post-graduation, ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- In almost all successful advertising campaigns, an appeal to emotion sparks a call-to-action that motivates viewers to become consumers. But according to research from a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign expert who studies consumer information-processing and memory, emotionally arousing advertisements may not always help improve consumers' immediate memory.

A new paper co-written by Hayden Noel, a clinical associate professor of business administration at the Gies College of Business at Illinois, finds that an ad's emotional arousal can have a negative effect on immediate ...

Using stem cells to regenerate parts of the skull, scientists corrected skull shape and reversed learning and memory deficits in young mice with craniosynostosis, a condition estimated to affect 1 in every 2,500 infants born in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The only current therapy is complex surgery within the first year of life, but skull defects often return afterward. The study, supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), could pave the way for more effective and less invasive therapies for children with craniosynostosis. ...

Humans feeding leftover lean meat to wolves during harsh winters may have had a role in the early domestication of dogs, towards the end of the last ice age (14,000 to 29,000 years ago), according to a study published in Scientific Reports.

Maria Lahtinen and colleagues used simple energy content calculations to estimate how much energy would have been left over by humans from the meat of species they may have hunted 14,000 to 29,000 years that were also typical wolf prey species, such as horses, moose and deer. The authors hypothesized that if wolves and humans had hunted the same animals during harsh winters, humans would have killed wolves to reduce competition rather than domesticate them. With the exception of Mustelids such as weasels, ...

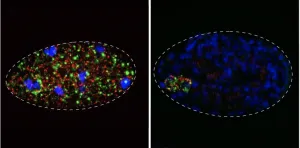

"Nature red in tooth and claw" - The battle to survive is fought down to the level of our genes. Toxin-antidote elements are gene pairs that spread in populations by killing non-carriers. Now, research by the Burga lab at IMBA and the Kruglyak lab at the University of California, Los Angeles shows that these elements are more common in nature than first thought and have evolved a wide range of mechanisms to force their inheritance and propagate in populations - a parasite within the genome.

Originally described in the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, toxin-antidote elements consist of two linked genes, a toxin and its antidote. While the toxin is loaded into eggs by mothers, only embryos that inherit the element express the antidote. Thus, the ...