(Press-News.org) Whenever an organism develops and forms organs, a tumour creates metastases or the immune system becomes active in inflammation, cells migrate within the body. As they do, they interact with surrounding tissues which influence their function. The migrating cells react to biochemical signals, as well as to biophysical properties of their environment, for example whether a tissue is soft or stiff. Gaining detailed knowledge about such processes provides scientists with a basis for understanding medical conditions and developing treatment approaches.

A team of biologists and mathematicians at the Universities of Münster and Erlangen-Nürnberg has now developed a new method for analysing cell migration processes in living organisms. The researchers investigated how primordial germ cells whose mode of locomotion is similar to other migrating cell types, including cancer cells, behave in zebrafish embryos when deprived of their biochemical guidance cue. The team developed new software that makes it possible to merge three-dimensional microscopic images of multiple embryos in order to recognise patterns in the distribution of cells and thus highlight tissues that influence cell migration. With the help of the software, researchers determined domains that the cells either avoided, to which they responded by clustering, or in which they maintained their normal distribution. In this way, they identified a physical barrier at the border of the organism's future backbone where the cells changed their path. "We expect that our experimental approach and the newly developed tools will be of great benefit in research on developmental biology, cell biology and biomedicine," explains Prof Dr Erez Raz, a cell biologist and project director at the Center for Molecular Biology of Inflammation at Münster University. The study has been published in the journal "Science Advances".

Details on methods and results

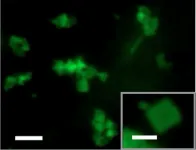

For their investigations, the researchers made use of primordial germ cells in zebrafish embryos. Primordial germ cells are the precursors of sperm and egg cells and, during the development of many organisms, they migrate to the place where the reproductive organs form. Normally, these cells are guided by chemokines - i.e. attractants produced by surrounding cells that initiate signalling pathways by binding to receptors on the primordial germ cells. By genetically modifying the cells, the scientists deactivated the chemokine receptor Cxcr4b so that the cells remained motile but no longer migrated in a directional manner. "Our idea was that the distribution of the cells within the organism - when not being controlled by guidance cues - can provide clues as to which tissues influence cell migration, and then we can analyse the properties of these tissues," explains ?ukasz Truszkowski, one of the three lead authors of the study.

"To obtain statistically significant data on the spatial distribution of the migrating cells, we needed to study several hundred zebrafish embryos, because at the developmental stage at which the cells are actively migrating, a single embryo has only around 20 primordial germ cells," says Sargon Groß-Thebing, also a first author and, like his colleague, a PhD student in the graduate programme of the Cells in Motion Interfaculty Centre at the University of Münster. In order to digitally merge the three-dimensional data of multiple embryos, the biology researchers joined forces with a team led by the mathematician Prof Dr Martin Burger, who was also conducting research at the University of Münster at that time and is now continuing the collaboration from the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg. The team developed a new software tool that pools the data automatically and recognises patterns in the distribution of primordial germ cells. The challenge was to account for the varying sizes and shapes of the individual zebrafish embryos and their precise three-dimensional orientation in the microscope images.

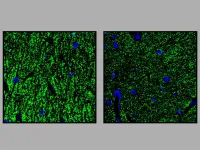

The software named "Landscape" aligns the images captured from all the embryos with each other. "Based on a segmentation of the cell nuclei, we can estimate the shape of the embryos and correct for their size. Afterwards, we adjust the orientation of the organisms", says mathematician Dr Daniel Tenbrinck, the third lead author of the study. In doing so, a tissue in the midline of the embryos serves as a reference structure which is marked by a tissue-specific expression of the so-called green fluorescent protein (GFP). In technical jargon the whole process is called image registration. The scientists verified the reliability of their algorithms by capturing several images of the same embryo, manipulating them with respect to size and image orientation, and testing the ability of the software to correct for the manipulations. To evaluate the ability of the software to recognise cell-accumulation patterns, they used microscopic images of normally developing embryos, in which the migrating cells accumulate at a known specific location in the embryo. The researchers also demonstrated that the software can be applied to embryos of another experimental model, embryos of the fruit fly Drosophila, which have a shape that is different from that of zebrafish embryos.

Using the new method, the researchers analysed the distribution of 21,000 primordial germ cells in 900 zebrafish embryos. As expected, the cells lacking a chemokine receptor were distributed in a pattern that differs from that observed in normal embryos. However, the cells were distributed in a distinct pattern that could not be recognised by monitoring single embryos. For example, in the midline of the embryo, the cells were absent. The researchers investigated that region more closely and found it to function as a physical barrier for the cells. When the cells came in contact with this border, they changed the distribution of actin protein within them, which in turn led to a change of cell migration direction and movement away from the barrier. A deeper understanding of how cells respond to physical barriers may be relevant in metastatic cancer cells that invade neighbouring tissues and where this process may be disrupted.

INFORMATION:

Original publication

Gross-Thebing S, Truszkowski L, Tenbrinck D, Sánchez-Iranzo H, Camelo C, Westerich KJ, Singh A, Maier P, Prengel J, Lange P, Hüwel J, Gaede F, Sasse R, Vos BE, Betz T, Matis M, Prevedel R, Luschnig S, Diz-Muñoz A, Burger M, Raz E. Using migrating cells as probes to illuminate features in live embryonic tissues. Sci Adv 2020;6: eabc5546.

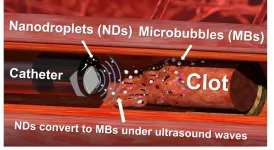

Engineering researchers have developed a new technique for eliminating particularly tough blood clots, using engineered nanodroplets and an ultrasound "drill" to break up the clots from the inside out. The technique has not yet gone through clinical testing. In vitro testing has shown promising results.

Specifically, the new approach is designed to treat retracted blood clots, which form over extended periods of time and are especially dense. These clots are particularly difficult to treat because they are less porous than other clots, making it hard for drugs ...

PHILADELPHIA - Medical school curriculums may misuse race and play a role in perpetuating physician bias, a team led by Penn Medicine researchers found in an analysis of curriculum from the preclinical phase of medical education. In a perspective piece published Tuesday in the New England Journal of Medicine, the researchers identified five key categories in which curriculum misrepresented race in class discussions, presentations, and assessments. The authors recommend that rather than oversimplifying conversations about how race affects diseases' prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment, medical school faculty must widen the lens to "impart an adequate and accurate understanding of the complexity ...

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

In what is believed to be the most comprehensive molecular characterization to date of the most common type of head and neck cancer, researchers from the Johns Hopkins departments of END ...

As the planet continues to warm, the twin challenges of diminishing water supply and growing energy demand will intensify. But water and energy are inextricably linked. For instance, nearly a fifth of California's energy goes toward water-related activities, while more than a tenth of the state's electricity comes from hydropower. As society tries to adapt to one challenge, it needs to ensure it doesn't worsen the other.

To this end, researchers from UC Santa Barbara, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and UC Berkeley have developed a framework to evaluate how different climate adaptations may impact this water-energy nexus. Their research appears in the open access journal Environmental Research Letters.

"Electricity and water systems are linked in many ...

Impaired intelligence, movement disorders and developmental delays are typical for a group of rare diseases that belong to GPI anchor deficiencies. Researchers from the University of Bonn and the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics used genetic engineering methods to create a mouse that mimics these patients very well. Studies in this animal model suggest that in GPI anchor deficiencies, a gene mutation impairs the transmission of stimuli at the synapses in the brain. This may explain the impairments associated with the disease. The results are now published ...

INDIANAPOLIS-- Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center published promising findings today in the New England Journal of Medicine on preventing a common complication to lifesaving blood stem cell transplantation in leukemia.

Sherif Farag, MD, PhD, found that using a drug approved for Type 2 diabetes reduces the risk of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), one of the most serious complications of blood stem cell transplantation. GVHD occurs in more than 30 percent of patients and can lead to severe side effects and potentially fatal results. Farag is ...

Chemists have developed a nanomaterial that they can trigger to shape shift -- from flat sheets to tubes and back to sheets again -- in a controllable fashion. The Journal of the American Chemical Society published a description of the nanomaterial, which was developed at Emory University and holds potential for a range of biomedical applications, from controlled-release drug delivery to tissue engineering.

The nanomaterial, which in sheet form is 10,000 times thinner than the width of a human hair, is made of synthetic collagen. Naturally occurring collagen is the most abundant protein in humans, making the new material intrinsically biocompatible.

"No one has previously made collagen ...

Alexandria, Va., USA -- The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted dental education and training. The study "COVID-19 and Dental and Dental Hygiene Students' Career Plans," published in the JDR Clinical & Translational Research (JDR CTR), examined the short-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental hygiene and dental students' career intentions.

An anonymous online survey was emailed to dental and dental hygiene students enrolled at Virginia Commonwealth University School of Dentistry, Richmond, USA. The survey consisted of 81 questions that covered a wide range of topics including demographics, anticipated educational debt, career plans post-graduation, ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- In almost all successful advertising campaigns, an appeal to emotion sparks a call-to-action that motivates viewers to become consumers. But according to research from a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign expert who studies consumer information-processing and memory, emotionally arousing advertisements may not always help improve consumers' immediate memory.

A new paper co-written by Hayden Noel, a clinical associate professor of business administration at the Gies College of Business at Illinois, finds that an ad's emotional arousal can have a negative effect on immediate ...

Using stem cells to regenerate parts of the skull, scientists corrected skull shape and reversed learning and memory deficits in young mice with craniosynostosis, a condition estimated to affect 1 in every 2,500 infants born in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The only current therapy is complex surgery within the first year of life, but skull defects often return afterward. The study, supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), could pave the way for more effective and less invasive therapies for children with craniosynostosis. ...