Researchers use LRZ HPC resources to perform largest-ever supersonic turbulence simulation

A multi-institution team from Australia and Germany simulates turbulence happening on both sides of the so-called "sonic scale," opening the door for more detailed and realistic galaxy formation simulations

2021-01-11

(Press-News.org) Through the centuries, scientists and non-scientists alike have looked at the night sky and felt excitement, intrigue, and overwhelming mystery while pondering questions about how our universe came to be, and how humanity developed and thrived in this exact place and time. Early astronomers painstakingly studied stars' subtle movements in the night sky to try and determine how our planet moves in relation to other celestial bodies. As technology has increased, so too has our understanding of how the universe works and our relative position within it.

What remains a mystery, however, is a more detailed understanding of how stars and planets formed in the first place. Astrophysicists and cosmologists understand that the movement of materials across the interstellar medium (ISM) helped form planets and stars, but how this complex mixture of gas and dust--the fuel for star formation--moves across the universe is even more mysterious.

To help better understand this mystery, researchers have turned to the power of high-performance computing (HPC) to develop high-resolution recreations of phenomena in the galaxy. Much like several terrestrial challenges in engineering and fluid dynamics research, astrophysicists are focused on developing a better understanding of the role of turbulence in helping shape our universe.

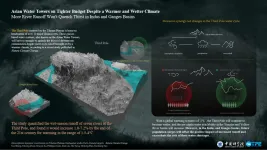

Over the last several years, a multi-institution collaboration being led by Australian National University Associate Professor Christoph Federrath and Heidelberg University Professor Ralf Klessen has been using HPC resources at the Leibniz Supercomputing Centre (LRZ) in Garching near Munich to study turbulence's influence on galaxy formation. The team recently revealed the so-called "sonic scale" of astrophysical turbulence--marking the transition moving from supersonic to subsonic speeds (faster or slower than the speed of sound, respectively)--creating the largest-ever simulation of supersonic turbulence in the process. The team published its research in Nature Astronomy.

Many scales in a simulation

To simulate turbulence in their research, Federrath and his collaborators needed to solve the complex equations of gas dynamics representing a wide variety of scales. Specifically, the team needed to simulate turbulent dynamics on both sides of the sonic scale in the complex, gaseous mixture travelling across the ISM. This meant having a sufficiently large simulation to capture these large-scale phenomena happening faster than the speed of sound, while also advancing the simulation slowly and with enough detail to accurately model the smaller, slower dynamics taking place at subsonic speeds.

"Turbulent flows only occur on scales far away from the energy source that drives on large scales, and also far away from the so-called dissipation (where the kinetic energy of the turbulence turns into heat) on small scales" Federrath said. "For our particular simulation, in which we want to resolve both the supersonic and the subsonic cascade of turbulence with the sonic scale in between, this requires at least 4 orders of magnitude in spatial scales to be resolved."

In addition to scale, the complexity of the simulations is another major computational challenge. While turbulence on Earth is one of the last major unsolved mysteries of physics, researchers who are studying terrestrial turbulence have one major advantage--the majority of these fluids are incompressible or only mildly compressible, meaning that the density of terrestrial fluids stays close to constant. In the ISM, though, the gaseous mix of elements is highly compressible, meaning researchers not only have to account for the large range of scales that influences turbulence, they also have to solve equations throughout the simulation to know the gases' density before proceeding.

Understanding the influence that density near the sonic scale plays in star formation is important for Federrath and his collaborators, because modern theories of star formation suggest that the sonic scale itself serves as a "Goldilocks zone" for star formation. Astrophysicists have long used similar terms to discuss how a planet's proximity to a star determines its ability to host life, but for star formation itself, the sonic scale strikes a balance between the forces of turbulence and gravity, creating the conditions for stars to more easily form. Scales larger than the sonic scale tend to have too much turbulence, leading to sparse star formation, while in smaller, subsonic regions, gravity wins the day and leads to localized clusters of stars forming.

In order to accurately simulate the sonic scale and the supersonic and subsonic scales on either side, the team worked with LRZ to scale its application to more than 65,000 compute cores on the SuperMUC HPC system. Having so many compute cores available allowed the team to create a simulation with more than 1 trillion resolution elements, making it the largest-ever simulation of its kind.

"With this simulation, we were able to resolve the sonic scale for the first time," Federrath said. "We found its location was close to theoretical predictions, but with certain modifications that will hopefully lead to more refined star formation models and more accurate predictions of star formation rates of molecular clouds in the universe. The formation of stars powers the evolution of galaxies on large scales and sets the initial conditions for planet formation on small scales, and turbulence is playing a big role in all of this. We ultimately hope that this simulation advances our understanding of the different types of turbulence on Earth and in space."

Cosmological collaborations and computational advancements

While the team is proud of its record-breaking simulation, it is already turning its attention to adding more details into its simulations, leading toward an even more accurate picture of star formation. Federrath indicated that the team planned to start incorporating the effects of magnetic fields on the simulation, leading to a substantial increase in memory for a simulation that already requires significant memory and computing power as well as multiple petabytes of storage--the current simulation requires 131 terabytes of memory and 23 terabytes of disk space per snapshot, with the whole simulation consisting of more than 100 snapshots.

Since he was working on his doctoral degree at the University of Heidelberg, Federrath has collaborated with staff at LRZ's AstroLab to help scale his simulations to take full advantage of modern HPC systems. Running the largest-ever simulation of its type serves as validation of the merits of this long-running collaboration. During this period, Federrath has worked closely with LRZ's Dr. Luigi Iapichino, Head of LRZ's AstroLab, who was a co-author on the Nature Astronomy publication.

"I see our mission as being the interface between the ever-increasing complexity of the HPC architectures, which is a burden on the application developers, and the scientists, which don't always have the right skill set for using HPC resource in the most effective way," Iapichino said. "From this viewpoint, collaborating with Christoph was quite simple because he is very skilled in programming for HPC performance. I am glad that in this kind of collaborations, application specialists are often full-fledged partners of researchers, because it stresses the key role centres' staffs play in the evolving HPC framework."

INFORMATION:

-Eric Gedenk

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-11

A shadow over the promising inhaled interferon beta COVID-19 therapy has been cleared with the discovery that although it appears to increase levels of ACE2 protein - coronavirus' key entry point into nose and lung cells - it predominantly increases levels of a short version of that protein, which the virus cannot bind to.

The virus that causes COVID-19, known as SARS-CoV-2, enters nose and lung cells through binding of its spike protein to the cell surface protein angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

Now a new, short, form of ACE2 has been identified by Professor Jane Lucas, Professor Donna Davies, Dr Gabrielle Wheway and Dr Vito Mennella at the University of Southampton and University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

The study, published in Nature Genetics, shows ...

2021-01-11

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - Jan. 11, 2021 - Most doctors would agree that advanced care planning (ACP) for patients, especially older adults, is important in providing the best and most appropriate health care over the course of a patient's life.

Unfortunately, the subject seldom comes up during regular clinic visits.

In a study conducted by doctors at Wake Forest Baptist Health, only 3.7% of primary care physicians had this conversation with their patients as part of their normal care. Yet in the same study, the researchers found that a new approach involving specially trained nurses substantially increased the frequency of doctors initiating ACP discussions with their patients.

The study is published ...

2021-01-11

Diets rich in certain plant-based foods are linked with the presence of gut microbes that are associated with a lower risk of developing conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to recent results from a large-scale international study that included researchers from King's College London, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the University of Trento, Italy, and health science start-up company ZOE.

Key Takeaways

The largest and most detailed study of its kind uncovered strong links between a person's diet, the microbes ...

2021-01-11

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Engineers at MIT and Imperial College London have developed a new way to generate tough, functional materials using a mixture of bacteria and yeast similar to the "kombucha mother" used to ferment tea.

Using this mixture, also called a SCOBY (symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast), the researchers were able to produce cellulose embedded with enzymes that can perform a variety of functions, such as sensing environmental pollutants. They also showed that they could incorporate yeast directly into the material, creating "living materials" that could ...

2021-01-11

Many Sub-Saharan countries have a desperate shortage of surgeons, and to ensure that as many patients as possible can be treated, some operations are carried out by medical professionals who are not specialists in surgery.

This approach, called task sharing, is supported by the World Health Organisation, but the practice remains controversial. Now a team of medical researchers from Norway, Sweden, Sierra Leone and the Netherlands shows that groin hernia operations performed by associate clinicians, who are trained medical personnel but not doctors, are just as safe and effective as those performed by doctors. The study has been published in JAMA Network Open.

"The study showed ...

2021-01-11

What The Study Did: This randomized clinical trial compares the effects of two antibiotic strategies (oral moxifloxacin versus intravenous ertapenem followed by oral levofloxacin) on hospital discharge without surgery and recurrent appendicitis over one year among adults presenting to the emergency department with uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

Authors: Paulina Salminen, M.D., Ph.D., of Turku University Hospital in Turku, Finland, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2020.23525)

Editor's ...

2021-01-11

New York, NY--January 11, 2021--Like a longtime couple who can predict each other's every move, a Columbia Engineering robot has learned to predict its partner robot's future actions and goals based on just a few initial video frames.

When two primates are cooped up together for a long time, we quickly learn to predict the near-term actions of our roommates, co-workers or family members. Our ability to anticipate the actions of others makes it easier for us to successfully live and work together. In contrast, even the most intelligent and advanced robots have remained notoriously inept at this sort of social communication. This may be about to change.

The study, conducted at Columbia Engineering's Creative Machines Lab led by Mechanical ...

2021-01-11

The Third Pole centered on the Tibetan Plateau is home to headwaters of over 10 major Asian rivers. These glacier-based water systems, also known as the Asian Water Towers, will have to struggle to quench the thirst of downstream communities despite more river runoff brought on by a warmer climate, according to a recent study published in Nature Climate Change.

By constraining earth system models for precipitation projections, together with estimated glacier melt contributions, the study quantified the wet-season runoff of seven rivers at the Third Pole, and found it would increase 1.0-7.2% by the end of the 21st century for warming in the range of 1.5-4°C. However, the study also showed that rising water demands from the growing population will outweigh ...

2021-01-11

To perform calculations, quantum computers need qubits to act as elementary building blocks that process and store information. Now, physicists have produced a new type of qubit that can be switched from a stable idle mode to a fast calculation mode. The concept would also allow a large number of qubits to be combined into a powerful quantum computer, as researchers from the University of Basel and TU Eindhoven have reported in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Compared with conventional bits, quantum bits (qubits) are much more fragile and can lose their information content very quickly. The challenge for quantum computing is therefore to keep the sensitive ...

2021-01-11

Diets rich in healthy and plant-based foods encourages the presence of gut microbes that are linked to a lower risk of common illnesses including heart disease, research has found.

A large-scale international study using metagenomics and blood chemical profiling has uncovered a panel of 15 gut microbes associated with lower risks of common conditions such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. The study has been published today in Nature Medicine from researchers at King's College London, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the University ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers use LRZ HPC resources to perform largest-ever supersonic turbulence simulation

A multi-institution team from Australia and Germany simulates turbulence happening on both sides of the so-called "sonic scale," opening the door for more detailed and realistic galaxy formation simulations