(Press-News.org) Astronomers have looked nine billion years into the past to find evidence that galaxy mergers in the early universe could shut down star formation and affect galaxy growth.

New research led by Durham University, UK, the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA)-Saclay and the University of Paris-Saclay, shows that a huge amount of star-forming gas was ejected into the intergalactic medium by the coming together of two galaxies.

The researchers say that this event, together with a large amount of star formation in the nuclear regions of the galaxy, would eventually deprive the merged galaxy - called ID2299 - of fuel for new stars. This would stop star formation for several hundred million years, effectively halting the galaxy's development.

Astronomers observe many massive, dead galaxies containing very old stars in the nearby Universe and don't exactly know how these galaxies have been formed.

Simulations suggest that winds generated by active black holes as they feed, or those created by intense star formation, are responsible for such deaths by expelling the gas from galaxies.

Now the Durham-led study offers galaxy mergers as another way of shutting down star formation and altering galaxy growth.

Observational features of winds and "tidal tails" caused by the gravitational interaction between galaxies in such mergers can be very similar, so the researchers suggest that some past results where galactic winds have been seen as the cause of halting star formation might need to be re-evaluated.

The findings are published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Lead author Dr Annagrazia Puglisi, in Durham University's Centre for Extragalactic Astronomy, said: "We don't yet know what the exact processes are behind the switching off of star formation in massive galaxies.

"Feedback driven winds from star formation or active black holes are thought to be the main responsible for expelling the gas and quenching the growth of massive galaxies.

"Our research provides compelling evidence that the gas being flung from ID2299 is likely to have been tidally ejected because of the merger between two gas rich spiral galaxies. The gravitational interaction between two galaxies can thus provide sufficient angular momentum to kick out part of the gas into the galaxy surroundings.

"This suggests that mergers are also capable of altering the future evolution of a galaxy by limiting its ability to form stars over millions of years and deserve more investigation when thinking about the factors that limit galaxy growth."

Due to the amount of time it takes the light from ID2299 to reach Earth the researchers were able to see the galaxy as it would have appeared nine billion years ago when it was in the late stages of its merger.

This is a time when the universe was only 4.5 billion years old and was in its most active, "young adult" phase if compared to a human life.

Using the European Southern Observatory's Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) telescope, in northern Chile, the researchers saw it was ejecting about half of its total gas reservoir into the galaxy surroundings.

Researchers were able to rule out star formation and the galaxy's active black hole as the reason for this ejection by comparing their measurements to previous studies and simulations and by measuring the physical properties of the escaped gas.

The rate at which the gas is being expelled from ID2299 is too high to have been caused by the energy created by a black hole or starburst as seen in previous studies, while simulations suggest that no black holes can kick out as much cold gas from a galaxy.

The excitation of the escaped gas is also not compatible with a wind generated by a black hole or the birth of new stars.

Co-author Dr Emanuele Daddi, from CEA-Saclay said: "This galaxy is witnessing a truly extreme event.

"It is probably caught during an important physical phase for galaxy evolution that occurs within a relatively short time window. We had to look at over 100 galaxies with ALMA to find it."

Fellow co-author Dr Jeremy Fensch, of the Centre de Recherche Astrophysique de Lyon, added: "Studying this single case unveiled the possibility that this type of event might not be unusual at all and that many galaxies suffered from this 'gravitational gas removal', including misinterpreted past observations.

"This might have huge consequences on our understanding of what actually shapes the evolution of galaxies."

INFORMATION:

The researchers now hope to obtain higher resolution images of ID2299 and other distant galaxy mergers and carry out computer simulations to further understand the effect galaxy mergers have on the life cycle of galaxies.

The research was funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council, part of UK Research and Innovation, Region Île-de-France, and the CEA-Enhanced Eurotalents program, co-funded by the FP7 Marie-Sk?odowska-Curie COFUND program, Comunidad de Madrid, Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MICIU), and co-financed by FEDER (European Regional Development Funds).

Through the centuries, scientists and non-scientists alike have looked at the night sky and felt excitement, intrigue, and overwhelming mystery while pondering questions about how our universe came to be, and how humanity developed and thrived in this exact place and time. Early astronomers painstakingly studied stars' subtle movements in the night sky to try and determine how our planet moves in relation to other celestial bodies. As technology has increased, so too has our understanding of how the universe works and our relative position within it.

What remains a mystery, however, is a more detailed understanding of how stars and planets formed in the first place. Astrophysicists and cosmologists understand that the movement of materials across the interstellar medium (ISM) helped ...

A shadow over the promising inhaled interferon beta COVID-19 therapy has been cleared with the discovery that although it appears to increase levels of ACE2 protein - coronavirus' key entry point into nose and lung cells - it predominantly increases levels of a short version of that protein, which the virus cannot bind to.

The virus that causes COVID-19, known as SARS-CoV-2, enters nose and lung cells through binding of its spike protein to the cell surface protein angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2).

Now a new, short, form of ACE2 has been identified by Professor Jane Lucas, Professor Donna Davies, Dr Gabrielle Wheway and Dr Vito Mennella at the University of Southampton and University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust.

The study, published in Nature Genetics, shows ...

WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. - Jan. 11, 2021 - Most doctors would agree that advanced care planning (ACP) for patients, especially older adults, is important in providing the best and most appropriate health care over the course of a patient's life.

Unfortunately, the subject seldom comes up during regular clinic visits.

In a study conducted by doctors at Wake Forest Baptist Health, only 3.7% of primary care physicians had this conversation with their patients as part of their normal care. Yet in the same study, the researchers found that a new approach involving specially trained nurses substantially increased the frequency of doctors initiating ACP discussions with their patients.

The study is published ...

Diets rich in certain plant-based foods are linked with the presence of gut microbes that are associated with a lower risk of developing conditions such as obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, according to recent results from a large-scale international study that included researchers from King's College London, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the University of Trento, Italy, and health science start-up company ZOE.

Key Takeaways

The largest and most detailed study of its kind uncovered strong links between a person's diet, the microbes ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Engineers at MIT and Imperial College London have developed a new way to generate tough, functional materials using a mixture of bacteria and yeast similar to the "kombucha mother" used to ferment tea.

Using this mixture, also called a SCOBY (symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast), the researchers were able to produce cellulose embedded with enzymes that can perform a variety of functions, such as sensing environmental pollutants. They also showed that they could incorporate yeast directly into the material, creating "living materials" that could ...

Many Sub-Saharan countries have a desperate shortage of surgeons, and to ensure that as many patients as possible can be treated, some operations are carried out by medical professionals who are not specialists in surgery.

This approach, called task sharing, is supported by the World Health Organisation, but the practice remains controversial. Now a team of medical researchers from Norway, Sweden, Sierra Leone and the Netherlands shows that groin hernia operations performed by associate clinicians, who are trained medical personnel but not doctors, are just as safe and effective as those performed by doctors. The study has been published in JAMA Network Open.

"The study showed ...

What The Study Did: This randomized clinical trial compares the effects of two antibiotic strategies (oral moxifloxacin versus intravenous ertapenem followed by oral levofloxacin) on hospital discharge without surgery and recurrent appendicitis over one year among adults presenting to the emergency department with uncomplicated acute appendicitis.

Authors: Paulina Salminen, M.D., Ph.D., of Turku University Hospital in Turku, Finland, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2020.23525)

Editor's ...

New York, NY--January 11, 2021--Like a longtime couple who can predict each other's every move, a Columbia Engineering robot has learned to predict its partner robot's future actions and goals based on just a few initial video frames.

When two primates are cooped up together for a long time, we quickly learn to predict the near-term actions of our roommates, co-workers or family members. Our ability to anticipate the actions of others makes it easier for us to successfully live and work together. In contrast, even the most intelligent and advanced robots have remained notoriously inept at this sort of social communication. This may be about to change.

The study, conducted at Columbia Engineering's Creative Machines Lab led by Mechanical ...

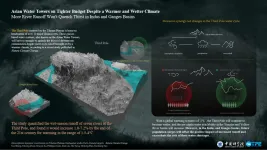

The Third Pole centered on the Tibetan Plateau is home to headwaters of over 10 major Asian rivers. These glacier-based water systems, also known as the Asian Water Towers, will have to struggle to quench the thirst of downstream communities despite more river runoff brought on by a warmer climate, according to a recent study published in Nature Climate Change.

By constraining earth system models for precipitation projections, together with estimated glacier melt contributions, the study quantified the wet-season runoff of seven rivers at the Third Pole, and found it would increase 1.0-7.2% by the end of the 21st century for warming in the range of 1.5-4°C. However, the study also showed that rising water demands from the growing population will outweigh ...

To perform calculations, quantum computers need qubits to act as elementary building blocks that process and store information. Now, physicists have produced a new type of qubit that can be switched from a stable idle mode to a fast calculation mode. The concept would also allow a large number of qubits to be combined into a powerful quantum computer, as researchers from the University of Basel and TU Eindhoven have reported in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

Compared with conventional bits, quantum bits (qubits) are much more fragile and can lose their information content very quickly. The challenge for quantum computing is therefore to keep the sensitive ...