(Press-News.org) Researchers from Skoltech and their colleagues have optimized data analysis for a common method of studying the 3D structure of DNA in single cells of a Drosophila fly. The new approach allows the scientists to peek with greater confidence into individual cells to study the unique ways DNA is packaged there and get closer to understanding this crucial process's underlying mechanisms. The paper was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The reason a roughly two-meter-long strand of DNA fits into the tiny nucleus of a human cell is that chromatin, a complex of DNA and proteins, packages it into compact but very complex structures. To study the way DNA is packaged, researchers worldwide have developed so-called chromosome conformation capture (3C) techniques, the most efficient of which is called Hi-C. Hi-C essentially catalogs all interacting fragments of a DNA strand via high-throughput sequencing.

Therein lies the problem, however: to work, Hi-C needs tens of micrograms of DNA, which means millions of cells, each with its unique spatial organization of chromatin, have to be averaged to get a snapshot that will inevitably miss some peculiarities of DNA packaging in single cells. Much like the 'average person' does not really exist, conventional Hi-C cannot tell you which of the multitudes of interactions actually happen in the same cell. Furthermore, this snapshot will hardly be useful in unraveling the physical processes that led to chromatin's particular 3D structure.

"We see certain structures, such as so-called Topologically Associating Domains, or TADs, in averaged contact maps, but we do not know whether they are artifacts of averaging or indeed exist in individual cells. Moreover, we know that cells even in one tissue may be quite diverse in terms of gene expression - so a natural question arises whether this diversity also exists on the structural level," says Mikhail Gelfand, Skoltech Vice President for Biomedical Research and a co-author of the new paper.

To overcome this hurdle and make the Hi-C process more suitable for single cells, researchers from several institutes advanced a single-cell Hi-C technique. The Skoltech team, led by Gelfand and assistant professor at the Skoltech Center of Life Sciences Ekaterina Khrameeva, took a challenge to optimize data processing for single-cell Hi-C and uncover the fundamental properties of Drosophila cells.

Their colleagues from the Institute of Gene Biology RAS and Lomonosov Moscow State University collaborate with researchers from French-Russian Interdisciplinary Scientific Center J.-V. Poncelet optimized the snHi-C procedure to make it suitable for experiments with Drosophila cells.

For the technique to work, the teams had to start with the same Hi-C steps of chemically 'freezing' the chromatin in place, strategically cutting the DNA and reassembling it so that fragments that were spatially close end up stitched together. But then, instead of using the DNA in bulk, they amplified the miniscule amounts of DNA from a single cell in each well using a polymerase from a phi29 bacteriophage. This phi29 polymerase is widely used in DNA amplification methods thanks to its ability to generate a lot of DNA from the tiniest of templates and make significantly fewer errors than other commonly-used polymerases.

However, it turned out that the handy DNA polymerase, while less error-prone, can still make random 'hops' between DNA molecules, creating artificial 'links' that Hi-C algorithms cannot distinguish from real interactions. So the researchers had to come up with an authenticity test, weeding out the random hops from real traces of interacting fragments.

They used their new technique on Drosophila cells to determine whether the fundamental ways of chromatin folding are the same across organisms. Earlier studies in mammalian cells pointed to the existence of TADs in average contact maps from Hi-C analysis, but not in individual cells. However, in Drosophila, single-cell data show that there are TADs in each particular cell. More research is needed to elucidate the biological mechanism that forms these stable domains, but the researchers suggest two models for these TADs. One implies that Drosophila chromatin is 'sticky' in a particular way, with different regions having different affinity to form contacts. The other, so-called loop extrusion mechanism, posits that large protein complexes create loops in the strand, bringing distant regions close together and creating a larger-scale structure.

"Perhaps, one of the most interesting questions to ask is whether chromatin folding rules are similar between different species of living organisms. Having single-cell Hi-C for the individual cells of Drosophila, we noticed that the genome of this insect is folded into domains, similar to the domains observed in single mammalian cells. However, these structures are much more ordered than in mammals," Aleksandra Galitsyna, PhD student at Skoltech and one of the paper's first co-authors, notes.

"We will continue studying chromatin architecture and dig into the mechanisms of loop and TAD formation. There are lots of unanswered questions in this area. We already know that these mechanisms might differ between some organisms, but what is the full picture of chromatin folding evolution? If we want to understand it at a sufficient scale, we would need to bridge gaps between well-studied organisms by resolving chromatin structure in the weird ones. To do that, we are already working on sponges, yeasts, and amoeba," Ekaterina Khrameeva says.

She adds that the team is also interested in how chromatin organization changes might be associated with the disease, organism development, and aging. "Assuming that chromatin architecture is tightly linked to gene expression, answering these questions might unravel the regulatory prerequisites of human development, aging, and disease," Khrameeva notes.

INFORMATION:

Other organizations involved in this research include the Institute of Gene Biology (Russian Academy of Sciences), Lomonosov Moscow State University, French National Centre for Scientific Research, French-Russian Interdisciplinary Scientific Center J.-V. Poncelet and other organizations.

A study of students at seven public universities across the United States has identified risk factors that may place students at higher risk for negative psychological impacts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors associated with greater risk of negative impacts include the amount of time students spend on screens each day, their gender, age and other characteristics.

Research has shown many college students faced significant mental health challenges going into the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts say the pandemic has added new stressors. The findings, published in the journal PLOS ONE, could help experts tailor services ...

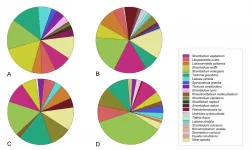

Announcing a new publication for Marine Life Science & Technology journal. In this research article the authors Hungchia Huang, Jinpeng Yang, Shixiang Huang, Bowei Gu, Ying Wang, Lei Wang and Nianzhi Jiao from Xiamen University, Xiamen, China and Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China consider the spatial distribution of planktonic ciliates in the western Pacific Ocea: along a transect from Shenzhen (China) to Pohnpei (Micronesia).

Planktonic ciliates have been recognized as major consumers of nano- and picoplankton in pelagic ecosystems, playing pivotal roles in the transfer ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - As a former school nurse in the Columbia Public Schools, Gretchen Carlisle would often interact with students with disabilities who took various medications or had seizures throughout the day. At some schools, the special education teacher would bring in dogs, guinea pigs and fish as a reward for good behavior, and Carlisle noticed what a calming presence the pets seemed to be for the students with disabilities.

Now a research scientist at the MU Research Center for Human-Animal Interaction (ReCHAI) in the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, Carlisle studies the benefits that companion animals can have on families. While there is plenty of ...

New Orleans, LA - Catherine O'Neal, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine's branch campus in Baton Rouge, is a co-author of a paper reporting that shortening the length of quarantine due to COVID exposure when supported by mid-quarantine testing may increase compliance among college athletes without increasing risk. The findings are published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's January 8, 2021 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), available here.

CDC partnered with representatives of the NCAA conferences to analyze retrospective data collected by participating colleges and universities. De-identified data from a total of 620 ...

Gut microbes passed from female mice to their offspring, or shared between mice that live together, may influence the animals' bone mass, says a new study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that treatments which alter the gut microbiome could help improve bone structure or treat conditions that weaken bones, such as osteoporosis.

"Genetics account for most of the variability in human bone density, but non-genetic factors such as gut microbes may also play a role," says lead author Abdul Malik Tyagi, Assistant Staff Scientist at the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Lipids at Emory Microbiome Research Center, Emory University, Georgia, US. "We wanted to investigate the influence of the microbiome on skeletal growth and bone mass development."

To ...

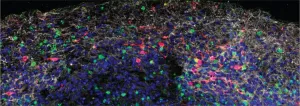

Using both mouse and human brain tissue, researchers at Yale School of Medicine have discovered that SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect the central nervous system and have begun to unravel some of the virus's effects on brain cells. The study, published today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), may help researchers develop treatments for the various neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Though COVID-19 is considered to primarily be a respiratory disease, SARS-CoV-2 can affect many other organs in the body, including, in some patients, the central nervous system, where infection is associated with ...

The first step in treating cancer is understanding how it starts, grows and spreads throughout the body. A relatively new cancer research approach is the study of metabolites, the products of different steps in cancer cell metabolism, and how those substances interact.

To date, research like this has focused mostly on cancerous tissues; however, normal tissues that surround tumors, known as the extratumoral microenvironment (EM), may have conditions favorable for tumor formation and should also be studied.

In a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE, researchers investigated the metabolites involved in the growth and spread of melanoma, a rare but deadly ...

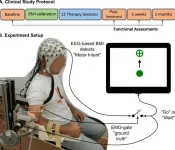

Almost 18,000 Americans experience traumatic spinal cord injuries every year. Many of these people are unable to use their hands and arms and can't do everyday tasks such as eating, grooming or drinking water without help.

Using physical therapy combined with a noninvasive method of stimulating nerve cells in the spinal cord, University of Washington researchers helped six Seattle area participants regain some hand and arm mobility. That increased mobility lasted at least three to six months after treatment had ended. The research team published these findings Jan. 5 in the journal ...

A recent study finds that, in the wake of a mass shooting, National Rifle Association (NRA) employees, donors and volunteers had extremely mixed emotions about the organization - reporting higher levels of both positive and negative feelings about the NRA, as compared to people with no NRA affiliation.

"We wanted to see what effect 'in-group' affiliation and political identity had on how people responded to the NRA's actions after a mass shooting," says Yang Cheng, co-author of the study and an assistant professor of communication at North Carolina State University. "The political findings were predictable - Republicans thought more favorably of the NRA than Democrats did. But the in-group affiliation was a lot more complex than ...

Stroke survivors who had ceased to benefit from conventional rehabilitation gained clinically significant arm movement and control by using an external robotic device powered by the patients' own brains.

The results of the clinical trial were described in the journal NeuroImage: Clinical.

Jose Luis Contreras-Vidal, director of the Non-Invasive Brain Machine Interface Systems Laboratory at the University of Houston, said testing showed most patients retained the benefits for at least two months after the therapy sessions ended, suggesting the potential for long-lasting gains. He is also Hugh Roy and Lillie Cranz Cullen Distinguished Professor of electrical and computer engineering.

The trial involved training stroke survivors with limited movement in one arm to use a brain-machine interface ...