(Press-News.org) Liver transplant priority in the U.S. goes to the sickest patients, which fails to consider other important factors, including how long patients are likely to survive post-transplant.

Researchers with Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine are collaborating with faculty at the University of Pennsylvania to develop a risk score that more comprehensively prioritizes liver cancer patients for transplantation.

Their paper documenting the development and validation of the LiTES-HCC score to predict post-transplant survival for hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver cancer, patients was published in the highly respected peer-reviewed Journal of Hepatology.

The authors looked retrospectively at national registry data of more than 6,500 adult deceased donor liver transplant recipients and found the 11 variables selected for their scoring system resulted in patient prioritization based on predicted survival and survival benefit, according to the study's lead author, David Goldberg, M.D., MSCE, associate professor of medicine in the Division of Digestive Health and Liver Diseases at the Miller School.

Dr. Goldberg is principal investigator for an ongoing National Institutes of Health grant aimed at redefining liver transplantation prioritization in the U.S.

"There are basically two large subsets of patients awaiting liver transplantation: those who have cirrhosis and complications from that, and then about 20% to 25% of transplants are for people who have liver cancer, which is a known complication of cirrhosis," Dr. Goldberg said. "Cirrhosis is the primary risk factor for developing liver cancer. When it is caught early enough and hasn't gotten too big, transplantation is the best treatment."

Since the early 2000s, patients who meet certain criteria based on tumor number and size get points or priority on the wait list for liver transplant.

"Livers are in short supply for transplantation. We have over 15,000 people waiting for livers," said Ezekiel J. Emanuel, M.D., Ph.D., vice provost for global initiatives and co-director of the Healthcare Transformation Institute at the University of Pennsylvania, who also served as co-author and co-investigator in the study. "As we know, in these circumstances who gets priority is really a life and death matter. We have shown that there are better ways to allocate livers saving more lives."

"For example, you could have a 75-year-old with diabetes, high blood pressure and kidney disease who has a 5 cm tumor have the same priority as someone who is 50, who has autoimmune liver disease and cancer and no other problem, even though the 50-year-old's expected survival is quite different," Dr. Goldberg said.

Researchers have developed other scores attempting to predict who will have better survival, but those scores have focused on tumor characteristics, including tumor size, number of tumors and blood biomarkers, and not on other health problems, such as diabetes or heart disease.

"Ours is the first validated score to predict survival after transplant for people with liver cancer that accounts for both their cancer-related factors but also non-cancer-related factors," Dr. Goldberg said.

Improving on the current system is important because there is a dramatic shortage of organs for transplantation, including livers.

The NIH grant has three aims: The first is the post-transplant research in this paper. Another journal has accepted Dr. Goldberg and colleagues' paper looking at using the score to predict survival in people without liver cancer. And now the researchers are developing a model to predict survival without a transplant.

"The broader goal of our work is to change liver transplant prioritization not just based on survival with the transplant but survival without the transplant. So, if someone is expected to live eight years with the transplant and four years without it, that is vastly different than someone who lives six years with a transplant and three months without," Dr. Goldberg said. "Ultimately, we will put this all together to determine who benefits most from a liver transplantation in order to redefine how we prioritize people for transplantation in the U.S. and maybe the world."

INFORMATION:

Egg cells are among the largest cells in the animal kingdom. If moved only by the random jostlings of water molecules, a protein could take hours or even days to drift from one side of a forming egg cell to the other. Luckily, nature has developed a faster way: cell-spanning whirlpools in the immature egg cells of animals such as mice, zebrafish and fruit flies. These vortices enable cross-cell commutes that take just a fraction of the time. But until now, scientists didn't know how these crucial flows formed.

Using mathematical modeling, researchers now have an answer. The gyres result from the collective behavior of rodlike molecular ...

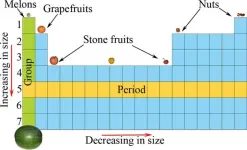

Many students, especially non-science majors, dread chemistry. The first lesson in an introductory chemistry course typically deals with how to interpret the periodic table of elements, but its complexity can be overwhelming to students with little or no previous exposure. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Journal of Chemical Education introduce an innovative way to make learning about the elements much more approachable -- by using "pseudo" periodic tables filled with superheroes, foods and apps.

One of the fundamental topics taught in first-year undergraduate chemistry courses is ...

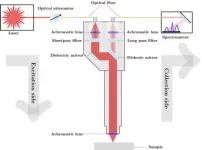

WASHINGTON -- In a new study, researchers show that a light-based analytical technique known as Raman spectroscopy could aid in early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC).

OSCC is the most prevalent type of oral cancer and ranks among the most common cancers diagnosed worldwide. Although effective treatments are available, the cancer is often not detected until a late stage, resulting in overall poor prognosis.

"Raman spectroscopy is not only label-free and non-invasive, but it can potentially be used in ambient light conditions," says research team leader Levi Matthies from University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany. "This makes it promising for use as a potential screening tool ...

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications, publishes selected abstracts from the 31st Great Wall International Cardiology (GW-ICC) Conference, October 19 - 25, 2020

Beijing, January 13, 2021: Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications (CVIA), in its role as the official journal of the Great Wall International Cardiology Conference (GW-ICC), has published selected abstracts from the 31st GW-ICC. Abstracts are now online at https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/cscript/cvia/2020/00000005/a00101s1/art00001

Co-Editors-in-Chief of CVIA Dr. C. Richard Conti, past president of the American College of Cardiology, and Dr Jianzeng Dong, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China commented that CVIA is delighted to be ...

Thousands of genetic markers have already been robustly associated with complex human traits, such as Alzheimer's disease, cancer, obesity, or height. To discover these associations, researchers need to compare the genomes of many individuals at millions of genetic locations or markers, and therefore require cost-effective genotyping technologies. A new statistical method, developed by Olivier Delaneau's group at the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics and the University of Lausanne (UNIL), offers game-changing possibilities. For less than $1 in computational cost, GLIMPSE is able to statistically infer a complete human genome from a very small amount of data. The method offers ...

Researchers at Brazil's National Space Research Institute (INPE), in partnership with colleagues in the United States, United Kingdom and South Africa, have recorded for the first time the formation and branching of luminous structures by lightning strikes.

Analyzing images captured by a super slow motion camera, they discovered why lightning strikes bifurcate and sometimes then form luminous structures interpreted by the human eye as flickers.

The study was supported by São Paulo Research Foundation - FAPESP. An article outlining its results is published in Scientific Reports.

"We managed to obtain the first optical observation of these phenomena and find a possible explanation for branching and flickering," Marcelo Magalhães Fares Saba, ...

Spatial isolation is known to promote speciation - but researchers at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich have now shown that, at least in yeast, the opposite is also true. New ecological variants can also evolve within thoroughly mixed populations.

The idea that speciation is based on the selection of variants that are better adapted to the local environmental conditions is at the heart of Charles Darwin's theory of the origin of species - and it is now known to be a central component of biological evolution, and thus of biodiversity. Geographic isolation of populations is often regarded as a necessary condition for ecotypes to diverge ...

PLYMOUTH MEETING, PA [January 13, 2021] -- New research in the January 2021 issue of JNCCN--Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network finds more than a third of eligible people miss timely screening tests for colorectal cancer and at least a quarter appear to miss timely screening tests for breast and cervical cancers. The study comes from the University of Alberta, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry in Alberta, Canada, with findings based on self-reported results from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) from 2007-2016. According to the author, the results also ...

WHAT:

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium bacteria (S. Typhimurium) commonly cause human gastroenteritis, inflammation of the lining of the intestines. The bacteria live inside the gut and can infect the epithelial cells that line its surface. Many studies have shown that Salmonella use a "run-and-tumble" method of short swimming periods (runs) punctuated by tumbles when they randomly change direction, but how they move within the gut is not well understood.

National Institutes of Health scientists and their colleagues believe they have identified a S. Typhimurium protein, McpC ...

Research into the neuronal basis of emotion processing has so far mostly taken place in the laboratory, i.e. in unrealistic conditions. Bochum-based biopsychologists have now studied couples in more natural conditions. Using electroencephalography (EEG), they recorded the brain activity of romantic couples at home while they cuddled, kissed or talked about happy memories together. The results confirmed the theory that positive emotions are mainly processed in the left half of the brain.

A group led by Dr. Julian Packheiser, Gesa Berretz, Celine Bahr, Lynn Schockenhoff and Professor Sebastian Ocklenburg from the Department of Biopsychology at Ruhr-Universität Bochum ...