(Press-News.org) Climate and changes in it have direct impacts on species of plant and animals - but climate may also shape more complex biological systems like food webs. Now a research group from the University of Helsinki has investigated how micro-climate shapes each level of the ecosystem, from species' abundances in predator communities to parasitism rates in key herbivores, and ultimately to damage suffered by plants. The results reveal how climate change may drastically reshape northern ecosystems.

Understanding the impact of climatic conditions on species interactions is imperative, as these interactions include such potent ecological forces as herbivory, pollination and parasitism.

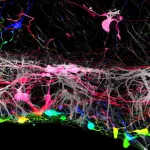

Lead researcher Tuomas Kankaanpaa from the Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, University of Helsinki, investigated how insect communities are assembled along micro-climatic gradients found on a mountainside in Northeast Greenland. He then compared this variation in environmental conditions to variation in the structure and function of different compartments of a food web. This web consists of a flowering plant as the primary producer (mountain avens), of moth larvae feeding on the flowers as consumers, and of parasitic wasps and flies, which, in turn, use moth larvae as living nurseries for their own offspring.

The study identified the micro-climate as an important factor in determining the local structure of parasitoid communities. Even within the uniform focal habitat type (heathland dominated by mountain avens), the abundances of species and the strengths interspecific interactions changed with climatic factors. As parasitoids are fairly specialized predators, they are particularly sensitive to environmental changes.

"To understand the more general impact of climate, we cannot always go species-by-species in each area. Rather, we need to uncover the uniting characteristics of species which show similar responses to climatic conditions," explains Kankaanpaa.

For the parasitoid insects of the North, one key trait turned out to be the way in which parasitoid species use their hosts. Species that spend considerable time dormant inside of their host, waiting for it to grow, form one group: they tend to prefer sites on which snow melts early and summers which are hot and dry. Conversely, species that attack full-sized host larvae or pupae appear to do better at sites where thicker snow cover offers protection from cold winter temperatures.

The larvae of the dominant avens-feeding moth species also preferred warm and dry areas in the landscape. The same association was evident in a long time-series collected as a part of an ongoing monitoring program at the Zackenberg research station. During the past two decades, winters with thin snow cover and warm summers have resulted in an increased proportion of avens flowers being consumed.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN SEASONALITY OF SPECIES SHIFTS?

A potentially serious consequence of climate change is a phenological mismatch - i.e. a situation in which the seasonality of interacting species change at a different rate. This can lead to situations where e.g. herbivorous insects escape some of their predators in time, thereby allowing herbivore populations to grow. The researchers found that the two dominant parasitoids preying on the focal moth larvae showed distinctly different temporal relationships with their host. One of the parasitoids matched the flowering of mountain avens and the development of its host larvae near perfectly across the wide range of spring arrival recorded within the study area. Yet, the other parasitoid species proved only loosely trimmed to coincide with specific life stages of its host. Such shifts can make a big difference once two parasitoids occupy the same host individual and competition within the still-living food source becomes physical. If one is then at the right stage and the other not, this can affect the outcome of the game.

"The parasitoids communities of the far North have previously received little attention. This is surprising, as these communities are species-poor, and thereby offer excellent opportunities to study what factors influence how species come together and interact," says Kankaanpaa.

The research group behind the study bridges two countries and two universities, the University of Helsinki and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU). It is led by Professor Tomas Roslin. The group has studied insect interactions across the world and in Greenland and regards the Arctic as an ideal observatory for monitoring the effects of climate change. In the High Arctic, the climate is changing especially fast - and within this zone, North East Greenland offers a region where other human impacts are minimal, thereby allowing researchers to isolate the unique effects of climate.

How insect communities vary along landscape-level micro-climates provides clues as to how such communities may change with time. Kankaanpää stresses that there is much work to be done before we can fully understand how climate change will reverberate through networks of live interactions. Do, for example, the outbreaks of a single herbivore species pose direct risks to those other herbivores with which it happens to share parasitoids? Can the feeding of large hoards of the joint enemies eventually extirpate the rarer host?

INFORMATION:

Astronomers using images from Kitt Peak National Observatory and Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory have created the largest ever map of the sky, comprising over a billion galaxies. The ninth and final data release from the ambitious DESI Legacy Imaging Surveys sets the stage for a ground-breaking 5-year survey with the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI), which aims to provide new insights into the nature of dark energy. The map was released today at the January 2021 meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

For millennia humans have used maps to understand and navigate our world and put ourselves in context: we rely on maps to show us where we are, where we came from, and where we're going. Astronomical maps continue this tradition on a vast scale. They ...

University of Otago researchers have added another piece to the puzzle about how best to translocate New Zealand lizards for conservation purposes - confine them.

In a paper just published in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology, the Department of Zoology researchers outlined how they translocated 19 barking geckos to Mana Island, using the method of penned release - enclosing them in a 100m² pen for three months so they get used to the site and hopefully establish a breeding population.

It was the first time such a method had been used with the species and the researchers found it worked well. The geckos' area use decreased over time, indicating ...

There are many components to aging, both mental and physical. When it comes to the infrastructure of the human body - the musculoskeletal system that includes muscles, bones, tendons and cartilage - age-associated decline is inevitable, and the rate of that decline increases the older we get. The loss of muscle function -- and often muscle mass -- is scientifically known as sarcopenia or dynapenia.

For adults in their 40s, sarcopenia is hardly noticeable -- about 3% muscle mass is lost each decade. For those aged 65 years and older, however, muscle decline can become much more rapid, with an average loss of 1% muscle mass each year. More importantly, sarcopenia is also marked by a decrease ...

Since 2013, China has implemented the strictest ever air pollution control policies, which resulted in substantial reductions in aerosol concentrations.

However, extreme and persistent haze events frequently occur during wintertime in China. In winter haze events, aerosol-related reductions of surface solar radiation (SSR) have comparable impacts on clouds over eastern provinces.

Recently, researchers from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory of the United States (PNNL) and their collaborators conducted a study to further understand the underlying chemical mechanisms driving winter haze events and how ...

A new type of stem cell - that is, a cell with regenerative abilities - could be closer on the horizon, a new study led by UNSW Sydney shows.

The stem cells (called induced multipotent stem cells, or iMS) can be made from easily accessible human cells - in this case, fat - and reprogrammed to act as stem cells.

The results of the animal study, which created human stem cells and tested their effectiveness in mice, was published online in Science Advances today - and while the results are encouraging, more research and tests are needed before any potential translation ...

Males are more likely to test positive for COVID-19, more likely to have complications and more likely to die from the virus than females, independent of age, according to a new study published this week in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Farhaan Vahidy of Houston Methodist Research Institute, US, and colleagues.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolds and evolves across the globe, researchers have identified population sub-groups with higher levels of disease vulnerability, such as those with advanced age or certain pre-existing conditions. Small studies from China and Europe have indicated that males tend to experience higher disease ...

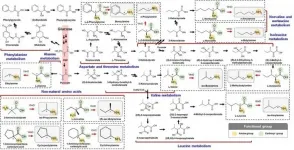

KAIST metabolic engineers presented the bio-based production of multiple short-chain primary amines that have a wide range of applications in chemical industries for the first time. The research team led by Distinguished Professor Sang Yup Lee from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering designed the novel biosynthetic pathways for short-chain primary amines by combining retrobiosynthesis and a precursor selection step.

The research team verified the newly designed pathways by confirming the in vivo production of 10 short-chain primary amines by supplying the precursors. Furthermore, the platform Escherichia ...

Women who are young, "conventionally attractive" and appear and act feminine are more likely to be believed when making accusations of sexual harassment, a new University of Washington-led study finds.

That leaves women who don't fit the prototype potentially facing greater hurdles when trying to convince a workplace or court that they have been harassed.

The study, involving more than 4,000 participants, reveals perceptions that primarily "prototypical" women are likely to be harassed. The research also showed that women outside of those socially determined norms ...

WASHINGTON -- Women who do not fit female stereotypes are less likely to be seen as victims of sexual harassment, and if they claim they were harassed, they are less likely to be believed, according to research published by the American Psychological Association.

"Sexual harassment is pervasive and causes significant harm, yet far too many women cannot access fairness, justice and legal protection, leaving them susceptible to further victimization and harm within the legal system," said Cheryl Kaiser, PhD, of the University of Washington and a co-author of the study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. "Our research found that a claim was deemed less ...

In experiments in mouse tissues and human cells, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say they have found that removing a membrane that lines the back of the eye may improve the success rate for regrowing nerve cells damaged by blinding diseases. The findings are specifically aimed at discovering new ways to reverse vision loss caused by glaucoma and other diseases that affect the optic nerve, the information highway from the eye to the brain.

"The idea of restoring vision to someone who has lost it from optic nerve disease has been considered science fiction for decades. ...