(Press-News.org) A novel new study suggests that the behavior public officials are now mandating or recommending unequivocally to slow the spread of surging COVID-19--wearing a face covering--should come with a caveat. If not accompanied by proper public education, the practice could lead to more infections.

The finding is part of an unique study, just published in JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, that was conducted by a team of health economists and public health faculty at the University of Vermont's Larner College of Medicine in partnership with public health officials for the state of Vermont.

The study combines survey data gathered from adults living in northwestern Vermont with test results that showed whether a subset of them had contracted COVID-19, a dual research approach that few COVID studies have employed. By correlating the two data sets, researchers were able to determine what behaviors and circumstances increased respondents' risk of becoming sick.

The key risk factor driving transmission of the disease, the study found, was the number of daily contacts participants had with other adults and seniors.

That had relevance for two other findings.

Those who wore masks had more of these daily contacts compared with those who didn't, and a higher proportion contracted the virus as a result.

Basic human psychology could be at work, said Eline van den Broek-Altenburg, an assistant professor and vice chair for Population Health Science in the Department of Radiology at the Larner College of Medicine and the study's principal investigator.

"When you wear a mask, you may have a deceptive sense of being protected and have more interactions with other people," she said.

The public health implications are clear. "Messaging that people need to wear a mask is essential, but insufficient," she said. "It should go hand in hand with education that masks don't give you a free pass to see as many people as you want. You still need to strictly limit your contacts."

Public education messaging should make clear how to wear a mask safely to limit infection, van den Broek-Altenburg added.

The study also found that participants' living environment determined how many contacts they had and affected their probability of becoming infected. A higher proportion of those living in apartments were infected with the virus compared with those who lived in single family homes.

"If you live in an apartment, you're going to see more people on a daily basis than if you live in a single family home, so you need to be as vigilant about social distancing," van den Broek-Altenburg said.

The study controlled for profession to prevent essential workers, who by definition have more contacts and are usually required to wear masks, from skewing the results.

"It's generally known that essential workers are at higher risk, and our study bore that out," van den Broek-Altenburg said. "We wanted to see what else predicted that people were going to get sick," she said.

Reported cases in Chittenden County, Vermont only one-fifth of likely total

The study provides the first estimate of unreported cases in Vermont's Chittenden County, where most study participants live. The survey found that 2.2 percent of the survey group had contracted the virus, suggesting that an estimated 3,621 Chittenden County residents were likely to have become ill, compared with just 662 reported cases, just 18%.

That figure translates to a hospitalization rate of 1.2% and adjusted infection fatality rate of 0.55%.

This finding is important for policy-makers, van den Broek-Altenburg said, in and out of Vermont.

"If you know how many people are sick or have been sick, you're much better equipped to make precise predictions of will happen in the future and fashion the appropriate policies," she said.

It also shows the importance of serologic and PCR testing of the general population, she said.

"If you only test symptomatic patients, you'll never be able to find out how many people have already had the virus. With our random sample study we were able to show that Vermont has so far only tested less than one-fifth of the people who have likely had the virus. To capture the larger population, random samples of the population are needed so we can also capture asymptomatic patients, which appears to be the majority of COVID-19 cases."

The study, among other things, is a proof of concept, van den Broek-Altenburg said.

"I hope it leads to other, larger studies that combine survey data with widespread testing. This approach is essential to both understanding the dynamics of this pandemic and planning our response to futures ones."

Ten of the 454 survey respondents who took the serologic test had antibodies for Covid-19, and one tested positive for the virus. Given the small number, researchers simplified their models and were able to reach a high confidence level in the two key findings.

"We tested our models and found that the results were robust through several different model specifications," van den Broek-Altenburg said.

To create the study group, the researchers sent a survey to 12,000 randomly selected people between the ages 18 and 70 who had at least one primary care visit at the University of Vermont Medical Center, which services primarily northwestern Vermont, in the past three years.

INFORMATION:

Coauthors on the study include Eline van den Broek-Altenburg, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Department of Radiology; Adam Atherly, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Center for Health Services Research; Sean Diehl, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Microbiology and Molecular Genetics; Kelsey Gleason University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine; Victoria Hart, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine; Charles MacLean, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine; Daniel Barkhuff, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Emergency Department; Mark Levine, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Department of Medicine; Jan Carney, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Department of Medicine.

Scientists who highlighted the bug-busting properties of bacteria in Northern Irish soil have made another exciting discovery in the quest to discover new antibiotics.

The Traditional Medicine Group, an international collaboration of scientists from Swansea University, Brazil and Northern Ireland, have discovered more antibiotic-producing species and believe they may even have identified new varieties of antibiotics with potentially life-saving consequences.

Antibiotic resistant superbugs could kill up to 1.3 million people in Europe by 2050 - the World Health Organisation (WHO) describes the problem as "one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today".

The search for replacement antibiotics to combat ...

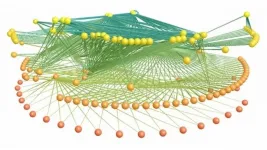

If you want to understand an ecosystem, look at what the species within it eat. In studying food webs -- how animals and plants in a community are connected through their dietary preferences -- ecologists can piece together how energy flows through an ecosystem and how stable it is to climate change and other disturbances. Studying ancient food webs can help scientists reconstruct communities of species, many long extinct, and even use those insights to figure out how modern-day communities might change in the future. There's just one problem: only some species left enough of a trace for scientists to find eons later, leaving large gaps in the fossil record -- and researchers' ability to piece together the food webs from the past.

"When things die and get preserved as fossils, all the ...

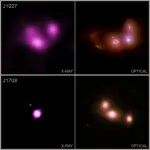

When three galaxies collide, what happens to the huge black holes at the centers of each? A new study using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and several other telescopes reveals new information about how many black holes are furiously growing after these galactic smash ups.

Astronomers want to learn more about galactic collisions because the subsequent mergers are a key way that galaxies and the giant black holes in their cores grow over cosmic time.

"There have been many studies of what happens to supermassive black holes when two galaxies merge," said Adi Foord of Stanford University, who led the study. "Ours is one of the first to systematically look at what happens to ...

The reproductive cycle of viruses requires self-assembly, maturation of virus particles and, after infection, the release of genetic material into a host cell. New physics-based technologies allow scientists to study the dynamics of this cycle and may eventually lead to new treatments. In his role as physical virologist, Wouter Roos, a physicist at the University of Groningen, together with two longtime colleagues, has written a review article on these new technologies, which was published in Nature Reviews Physics on 12 January.

'Physics has been used for a long time to study viruses,' says Roos. 'The laws of ...

In the inaugural issue of the journal Nature Aging a research team led by aging expert Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, dean of Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, synthesizes converging evidence that the aging-related pathophysiology underpinning the clinical presentation of phenotypic frailty (termed as "physical frailty" here) is a state of lower functioning due to severe dysregulation of the complex dynamics in our bodies that maintains health and resilience. When severity passes a threshold, the clinical syndrome and its phenotype are diagnosable. This paper summarizes the evidence meeting criteria for physical frailty as a product of complex system dysregulation. ...

Astronomers have curated the most complete list of nearby brown dwarfs to date thanks to discoveries made by thousands of volunteers participating in the Backyard Worlds citizen science project. The list and 3D map of 525 brown dwarfs -- including 38 reported for the first time -- incorporate observations from a host of astronomical instruments including several NOIRLab facilities. The results confirm that the Sun's neighborhood appears surprisingly diverse relative to other parts of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Mapping out our own small pocket of the Universe is a time-honored quest within astronomy, and ...

NEW YORK (January 14) -- A new study co-authored by researchers from the Wildlife Conservation Society's (WCS) Global Conservation Program and the University of British Columbia (UBC) Faculty of Forestry introduces a classification called Resistance-Resilience-Transformation (RRT) that enables the assessment of whether and to what extent a management shift toward transformative action is occurring in conservation. The team applied this classification to 104 climate adaptation projects funded by the WCS Climate Adaptation Fund over the past decade and found differential responses toward transformation ...

A wide breadth of behaviors surrounding oral sex may affect the risk of oral HPV infection and of a virus-associated head and neck cancer that can be spread through this route, a new study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center suggests. These findings add nuance to the connection between oral sex and oropharyngeal cancer -- tumors that occur in the mouth and throat -- and could help inform research and public health efforts aimed at preventing this disease.

The findings were reported Jan. 11 in the journal Cancer.

In the early 1980s, researchers realized that nearly all cervical cancer is caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), a DNA virus from the Papillomaviridae family. Although about 90% of HPV infections ...

The higher a person's income, the more likely they were to protect themselves at the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic in the United States, Johns Hopkins University economists find.

When it comes to adopting behaviors including social distancing and mask wearing, the team detected a striking link to their financial well-being. People who made around $230,000 a year were as much as 54% more likely to increase these types of self-protective behaviors compared to people making about $13,000.

"We need to understand these differences because we can wring our hands, and we can blame and shame, but in a way it doesn't matter," said Nick Papageorge, the Broadus Mitchell Associate Professor of Economics. "Policymakers just need to recognize who is going ...

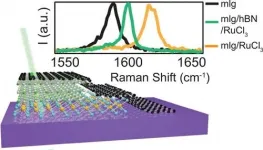

Physicists at Washington University in St. Louis have discovered how to locally add electrical charge to an atomically thin graphene device by layering flakes of another thin material, alpha-RuCl3, on top of it.

A paper published in the journal Nano Letters describes the charge transfer process in detail. Gaining control of the flow of electrical current through atomically thin materials is important to potential future applications in photovoltaics or computing.

"In my field, where we study van der Waals heterostructures made by custom-stacking atomically ...