(Press-News.org) TROY, N.Y. -- As cancer and tumor cells move inside the human body, they impart and are subject to mechanical forces. In order to understand how these actions affect cancer cell growth, spread, and invasion, a team of engineers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute is developing new models that mimic aspects of the mechanical environment within the body, providing new insight into how and why tumors develop in certain ways.

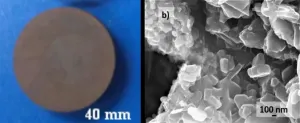

In research published today in Integrative Biology, a team of engineers from Rensselaer developed an in vitro -- in the lab -- lymphatic vessel model to study the growth of tumor emboli, collections of tumor cells within vessels that are often associated with increased metastasis and tumor recurrence.

"The growth of tumor emboli is important for the spread and metastasis of certain types of cancers. For example, inflammatory breast cancer has this growth pattern of just massive spread of emboli growing within dermal lymphatic vessels, in the breast, and it's very aggressive in that way," said Kristen Mills, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Rensselaer, who led this research. "This growth of tumor emboli hasn't really been studied very much."

Previous tumor models in the lab have used unconstrained spheroids of tumor cells that don't allow researchers to study the mechanical interactions that truly happen within the physical boundaries of a tubular-shaped vessel. To more closely mimic what happens in the body, Mills and her team modeled a lymphatic vessel in the lab using a small channel in a gel. They placed these channels within either stiff or soft bioinert gel, in order to mimic the constraints that tumor emboli may encounter in stiff, diseased tissue, or soft, healthy tissue.

To incorporate the varying growth behaviors of cells, the team used breast and colon cancer cell aggregates to model the emboli, one which is more aggressive, the other less.

Researchers found that the model of a stiff tumor environment constrained both types of tumor emboli to the cylindrical channel, causing rapid growth of the emboli along the vessel. But, they found that the growth of the cancer cells was different, based on their type, in the softer matrix model, which mimics healthy colon or breast tissue.

The aggressive cells were not affected by the presence of the open channel at all and grew as a sphere, bulging into the matrix, while the less aggressive cells first grew along the channel for several days before bulging into the matrix. The researchers linked the differences in growth to the force generation capability of the cancer cells. Independent measurements indicated that the aggressive cancer cells were capable of exerting significantly more force than the less aggressive cells.

Growth along a vessel or channel is problematic, Mills said, because the cells within the tumor have constant access to life-sustaining nutrients through the vessel wall. When the tumor cells grow in a sphere and begin to bulge, Mills said, the cells in the center of that mass get farther and farther away from nutrients until they are cut off and eventually die. This information could be critical for therapeutic design and prescription.

"We think this is important because it somehow suggests that, if the tumor tissue surrounding these vessels has been abnormally stiffened through disease, or if -- for example -- the breast tissue is already denser or stiffer, you might really see much more growth within the vessels than with a softer tissue," said Mills, who is also a member of the Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies (CBIS) at Rensselaer.

Jonathan Kulwatno, a graduate student in biomedical engineering at Rensselaer, was first author on this paper. Mills and Kulwatno collaborated with researchers from Mount Sinai.

This unique, mechanical engineering approach to studying cancer is a hallmark of the transformative work being done within CBIS, where researchers like Mills can collaborate across disciplines with other engineers and scientists working in similar areas.

"Professor Mills' engineering approach to studying cancer is laying a critical foundation, where interdisciplinary approaches are used to understand the mechanobiology of cancer with an eventual therapeutic goal," said Deepak Vashishth, the director of CBIS.

As Mills and her team continue their research, she said, they look for new ways to make these models more complex without losing the ability to isolate critical mechanical mechanisms.

INFORMATION:

About Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Founded in 1824, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute is America's first technological research university. Rensselaer encompasses five schools, 32 research centers, more than 145 academic programs, and a dynamic community made up of more than 7,600 students and over 100,000 living alumni. Rensselaer faculty and alumni include more than 145 National Academy members, six members of the National Inventors Hall of Fame, six National Medal of Technology winners, five National Medal of Science winners, and a Nobel Prize winner in Physics. With nearly 200 years of experience advancing scientific and technological knowledge, Rensselaer remains focused on addressing global challenges with a spirit of ingenuity and collaboration. To learn more, please visit http://www.rpi.edu.

Superconductivity already has a variety of practical applications, such as medical imaging and levitating transportation like the ever-popular maglev systems. However, to ensure that the benefits of applied superconductors keep spreading further into other technological fields, we need to find ways of not only improving their performance, but also making them more accessible and simpler to fabricate.

In this regard, magnesium diboride (MgB2) has attracted the attention of researchers since its discovery as a superconductor with multiple advantages. It is a lightweight, easily processible material made from widely abundant ...

MEDFORD/SOMERVILLE, Mass. (Jan. 14, 2021)-- Exposure to discrimination plays a significant role in the risk of developing anxiety and related disorders, even - in a first - after accounting for potential genetic risks, according to a multidisciplinary team of health researchers led by Tufts University and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Researchers determined that even after controlling for genetic risk for anxiety, depression, and neuroticism, greater reports of discrimination experiences remained associated with higher scores of anxiety and related disorders. The findings, recently ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Scientists have found a new species of fleshy verdigris lichen, thanks to DNA analysis of museum specimens. Misidentified by its original collectors, the lichen is only known from 32 specimens collected in North and Central Florida scrubland between 1885 and 1985. Now the hunt is on to find it in the wild - if it still exists.

The lichen, named Cora timucua in honor of Florida's Timucua people, is critically endangered, even more so than the federally protected Florida perforate reindeer lichen, and possibly extinct. Researchers are holding out hope that C. timucua may persist in undisturbed pockets of the state's dwindling pine scrub habitat, though recent searches came up empty.

"The million-dollar question is 'Where is this lichen?'" said Laurel Kaminsky, a digitization ...

A novel new study suggests that the behavior public officials are now mandating or recommending unequivocally to slow the spread of surging COVID-19--wearing a face covering--should come with a caveat. If not accompanied by proper public education, the practice could lead to more infections.

The finding is part of an unique study, just published in JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, that was conducted by a team of health economists and public health faculty at the University of Vermont's Larner College of Medicine in partnership with public health officials for the state of Vermont.

The study combines survey data gathered from adults living in northwestern Vermont with test results that showed whether a subset of them had contracted COVID-19, a dual research ...

Scientists who highlighted the bug-busting properties of bacteria in Northern Irish soil have made another exciting discovery in the quest to discover new antibiotics.

The Traditional Medicine Group, an international collaboration of scientists from Swansea University, Brazil and Northern Ireland, have discovered more antibiotic-producing species and believe they may even have identified new varieties of antibiotics with potentially life-saving consequences.

Antibiotic resistant superbugs could kill up to 1.3 million people in Europe by 2050 - the World Health Organisation (WHO) describes the problem as "one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today".

The search for replacement antibiotics to combat ...

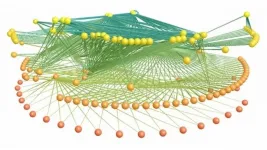

If you want to understand an ecosystem, look at what the species within it eat. In studying food webs -- how animals and plants in a community are connected through their dietary preferences -- ecologists can piece together how energy flows through an ecosystem and how stable it is to climate change and other disturbances. Studying ancient food webs can help scientists reconstruct communities of species, many long extinct, and even use those insights to figure out how modern-day communities might change in the future. There's just one problem: only some species left enough of a trace for scientists to find eons later, leaving large gaps in the fossil record -- and researchers' ability to piece together the food webs from the past.

"When things die and get preserved as fossils, all the ...

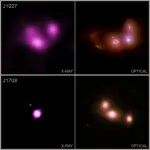

When three galaxies collide, what happens to the huge black holes at the centers of each? A new study using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and several other telescopes reveals new information about how many black holes are furiously growing after these galactic smash ups.

Astronomers want to learn more about galactic collisions because the subsequent mergers are a key way that galaxies and the giant black holes in their cores grow over cosmic time.

"There have been many studies of what happens to supermassive black holes when two galaxies merge," said Adi Foord of Stanford University, who led the study. "Ours is one of the first to systematically look at what happens to ...

The reproductive cycle of viruses requires self-assembly, maturation of virus particles and, after infection, the release of genetic material into a host cell. New physics-based technologies allow scientists to study the dynamics of this cycle and may eventually lead to new treatments. In his role as physical virologist, Wouter Roos, a physicist at the University of Groningen, together with two longtime colleagues, has written a review article on these new technologies, which was published in Nature Reviews Physics on 12 January.

'Physics has been used for a long time to study viruses,' says Roos. 'The laws of ...

In the inaugural issue of the journal Nature Aging a research team led by aging expert Linda P. Fried, MD, MPH, dean of Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, synthesizes converging evidence that the aging-related pathophysiology underpinning the clinical presentation of phenotypic frailty (termed as "physical frailty" here) is a state of lower functioning due to severe dysregulation of the complex dynamics in our bodies that maintains health and resilience. When severity passes a threshold, the clinical syndrome and its phenotype are diagnosable. This paper summarizes the evidence meeting criteria for physical frailty as a product of complex system dysregulation. ...

Astronomers have curated the most complete list of nearby brown dwarfs to date thanks to discoveries made by thousands of volunteers participating in the Backyard Worlds citizen science project. The list and 3D map of 525 brown dwarfs -- including 38 reported for the first time -- incorporate observations from a host of astronomical instruments including several NOIRLab facilities. The results confirm that the Sun's neighborhood appears surprisingly diverse relative to other parts of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Mapping out our own small pocket of the Universe is a time-honored quest within astronomy, and ...