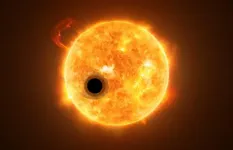

(Press-News.org) The core mass of the giant exoplanet WASP-107b is much lower than what was thought necessary to build up the immense gas envelope surrounding giant planets like Jupiter and Saturn, astronomers at Université de Montréal have found.

This intriguing discovery by Ph.D. student Caroline Piaulet of UdeM's Institute for Research on Exoplanets (iREx) suggests that gas-giant planets form a lot more easily than previously believed.

Piaulet is part of the groundbreaking research team of UdeM astrophysics professor Björn Benneke that in 2019 announced the first detection of water on an exoplanet located in its star's habitable zone.

Published today in the Astronomical Journal with colleagues in Canada, the U.S., Germany and Japan, the new analysis of WASP-107b's internal structure "has big implications," said Benneke.

"This work addresses the very foundations of how giant planets can form and grow," he said. "It provides concrete proof that massive accretion of a gas envelope can be triggered for cores that are much less massive than previously thought."

As big as Jupiter but 10 times lighter

WASP-107b was first detected in 2017 around WASP-107, a star about 212 light years from Earth in the Virgo constellation. The planet is very close to its star -- over 16 times closer than the Earth is to the Sun. As big as Jupiter but 10 times lighter, WASP-107b is one of the least dense exoplanets known: a type that astrophysicists have dubbed "super-puff" or "cotton-candy" planets.

Piaulet and her team first used observations of WASP-107b obtained at the Keck Observatory in Hawai'i to assess its mass more accurately. They used the radial velocity method, which allows scientists to determine a planet's mass by observing the wobbling motion of its host star due to the planet's gravitational pull. They concluded that the mass of WASP-107b is about one tenth that of Jupiter, or about 30 times that of Earth.

The team then did an analysis to determine the planet's most likely internal structure. They came to a surprising conclusion: with such a low density, the planet must have a solid core of no more than four times the mass of the Earth. This means that more than 85 percent of its mass is included in the thick layer of gas that surrounds this core. By comparison, Neptune, which has a similar mass to WASP-107b, only has 5 to 15 percent of its total mass in its gas layer.

"We had a lot of questions about WASP-107b," said Piaulet. "How could a planet of such low density form? And how did it keep its huge layer of gas from escaping, especially given the planet's close proximity to its star?

"This motivated us to do a thorough analysis to determine its formation history."

A gas giant in the making

Planets form in the disc of dust and gas that surrounds a young star called a protoplanetary disc. Classical models of gas-giant planet formation are based on Jupiter and Saturn. In these, a solid core at least 10 times more massive than the Earth is needed to accumulate a large amount of gas before the disc dissipates.

Without a massive core, gas-giant planets were not thought able to cross the critical threshold necessary to build up and retain their large gas envelopes.

How then do explain the existence of WASP-107b, which has a much less massive core? McGill University professor and iREx member Eve Lee, a world-renowned expert on super-puff planets like WASP-107b, has several hypotheses.

"For WASP-107b, the most plausible scenario is that the planet formed far away from the star, where the gas in the disc is cold enough that gas accretion can occur very quickly," she said. "The planet was later able to migrate to its current position, either through interactions with the disc or with other planets in the system."

Discovery of a second planet, WASP-107c

The Keck observations of the WASP-107 system cover a much longer period of time than previous studies have, allowing the UdeM-led research team to make an additional discovery: the existence of a second planet, WASP-107c, with a mass of about one-third that of Jupiter, considerably more than WASP-107b's.

WASP-107c is also much farther from the central star; it takes three years to complete one orbit around it, compared to only 5.7 days for WASP-107b. Also interesting: the eccentricity of this second planet is high, meaning its trajectory around its star is more oval than circular.

"WASP-107c has in some respects kept the memory of what happened in its system," said Piaulet. "Its great eccentricity hints at a rather chaotic past, with interactions between the planets which could have led to significant displacements, like the one suspected for WASP-107b."

Several more questions

Beyond its formation history, there are still many mysteries surrounding WASP-107b. Studies of the planet's atmosphere with the Hubble Space Telescope published in 2018 revealed one surprise: it contains very little methane.

"That's strange, because for this type of planet, methane should be abundant," said Piaulet. "We're now reanalysing Hubble's observations with the new mass of the planet to see how it will affect the results, and to examine what mechanisms might explain the destruction of methane."

The young researcher plans to continue studying WASP-107b, hopefully with the James Webb Space Telescope set to launch in 2021, which will provide a much more precise idea of the composition of the planet's atmosphere.

"Exoplanets like WASP-107b that have no analogue in our Solar System allow us to better understand the mechanisms of planet formation in general and the resulting variety of exoplanets," she said. "It motivates us to study them in great detail."

INFORMATION:

About this study

"WASP-107b's density is even lower: a case study for the physics of gas envelope accretion and orbital migration," by Caroline Piaulet et al., was posted today in the Astronomical Journal. DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/abcd3c. In addition to Piaulet (iREx Ph.D. student, Université de Montréal) and professors Björn Benneke (iREx, Université de Montréal) and Eve Lee (iREx, McGill Space Institute, McGill University), the research team includes Daniel Thorngren (iREx Postdoctoral Fellow, Université de Montréal) and Merrin Peterson (iREx M.Sc student), and 19 other co-authors from Canada, the United States, Germany and Japan.

Indiana Jones and Lara Croft have a lot to answer for. Public perceptions of archaeology are often thoroughly outdated, and these characterisations do little to help.

Yet archaeology as practiced today bears virtually no resemblance to the tomb raiding portrayed in movies and video games. Indeed, it bears little resemblance to even more scholarly depictions of the discipline in the entertainment sphere.

A paper published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution aims to give pause to an audience that has been largely prepared to take such out-of-touch depictions at face value. It reveals an archaeology practiced by scientists in white lab coats, using multi-million-euro instrumentation and state of the art computers.

It also reveals an archaeology poised to ...

Irvine, Calif. -- Future climate change will cause a regionally uneven shifting of the tropical rain belt - a narrow band of heavy precipitation near the equator - according to researchers at the University of California, Irvine and other institutions. This development may threaten food security for billions of people.

In a study published today in Nature Climate Change, the interdisciplinary team of environmental engineers, Earth system scientists and data science experts stressed that not all parts of the tropics will be affected equally. For instance, the rain belt ...

Range anxiety, the fear of running out of power before being able to recharge an electric vehicle, may be a thing of the past, according to a team of Penn State engineers who are looking at lithium iron phosphate batteries that have a range of 250 miles with the ability to charge in 10 minutes.

"We developed a pretty clever battery for mass-market electric vehicles with cost parity with combustion engine vehicles," said Chao-Yang Wang, William E. Diefenderfer Chair of mechanical engineering, professor of chemical engineering and professor of materials science and engineering, and director of the Electrochemical Engine Center at Penn State. "There ...

Targeted neuromodulation tailored to individual patients' distinctive symptoms is an increasingly common way of correcting misfiring brain circuits in people with epilepsy or Parkinson's disease. Now, scientists at UC San Francisco's Dolby Family Center for Mood Disorders have demonstrated a novel personalized neuromodulation approach that -- at least in one patient -- was able to provide relief from symptoms of severe treatment-resistant depression within minutes.

The approach is being developed specifically as a potential treatment for the significant fraction of people with debilitating depression ...

More than 3,000 animal species in the world today are considered endangered, with hundreds more categorized as vulnerable. Currently, ecologists don't have reliable tools to predict when a species may become at risk.

A new paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, "Management implications of long transients in ecological systems," focuses on the transient nature of species' and ecosystem stability and illustrates how management practices can be adjusted to better prepare for possible system flips. Some helpful modeling approaches are also offered, including one tool that may help identify potentially ...

Researchers at the University of Adelaide have found new evidence about the positive role of androgens in breast cancer treatment with immediate implications for women with estrogen receptor-driven metastatic disease.

Published today in Nature Medicine, the international study conducted in collaboration with the Garvan Institute of Medical Research, looked at the role of androgens - commonly thought of as male sex hormones but also found at lower levels in women - as a potential treatment for estrogen receptor positive breast cancer.

Watch a video explainer about the new ...

Some of the low-carbon policy options currently used by governments may be detrimental to the households and small businesses less able to manage added short-term costs from energy price hikes, according to a new study.

However, it also suggests that this menu of decarbonising policies, from quotas to feed-in tariffs, can be designed and balanced to benefit local firms and lower-income families - vital for achieving 'Net Zero' carbon and a green recovery.

University of Cambridge researchers combed through thousands of studies to create the most comprehensive analysis to date of widely used types of low-carbon policy, and compared how they perform in areas such as cost and competitiveness. ...

Some of the low-carbon policy options currently used by governments may be detrimental to the households and small businesses less able to manage added short-term costs from energy price hikes, according to a new study.

However, it also suggests that this menu of decarbonising policies, from quotas to feed-in tariffs, can be designed and balanced to benefit local firms and lower-income families - vital for achieving 'Net Zero' carbon and a green recovery.

University of Cambridge researchers combed through thousands of studies to create the most comprehensive analysis to date of widely used types of low-carbon policy, and compared how they perform in areas such ...

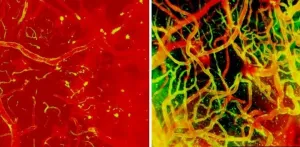

Researchers from the National Institutes of Health have discovered Jekyll and Hyde immune cells in the brain that ultimately help with brain repair but early after injury can lead to fatal swelling, suggesting that timing may be critical when administering treatment. These dual-purpose cells, which are called myelomonocytic cells and which are carried to the brain by the blood, are just one type of brain immune cell that NIH researchers tracked, watching in real-time as the brain repaired itself after injury. The study, published in Nature Neuroscience, ...

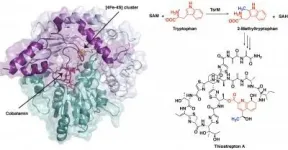

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Images of a protein involved in creating a potent antibiotic reveal the unusual first steps of the antibiotic's synthesis. The improved understanding of the chemistry behind this process, detailed in a new study led by Penn State chemists, could allow researchers to adapt this and similar compounds for use in human medicine.

"The antibiotic thiostrepton is very potent against Gram-positive pathogens and can even target certain breast cancer cells in culture," said Squire Booker, a biochemist at Penn State and investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. "While it has been used ...