(Press-News.org) HOUSTON - (Jan. 19, 2021) - Carbon nanotube fibers are not nearly as strong as the nanotubes they contain, but Rice University researchers are working to close the gap.

A computational model by materials theorist Boris Yakobson and his team at Rice's Brown School of Engineering establishes a universal scaling relationship between nanotube length and friction between them in a bundle, parameters that can be used to fine-tune fiber properties for strength.

The model is a tool for scientists and engineers who develop conductive fibers for aerospace, automotive, medical and textile applications like smart clothing. Carbon nanotube fibers have been considered as a possible basis for a space elevator, a project Yakobson has studied.

The research is detailed in the American Chemical Society journal ACS Nano.

As grown, individual carbon nanotubes are basically rolled-up tubes of graphene, one of the strongest known materials. But when bundled, as Rice and other labs have been doing since 2013, the threadlike fibers are far weaker, about one-hundredth the strength of individual tubes, according to the researchers.

"One single nanotube is about the strongest thing you can imagine, because of its very strong carbon-carbon bonds," said Rice assistant research professor Evgeni Penev, a longtime member of the Yakobson group. "But when you start making things out of nanotubes, those things are much weaker than you would expect. Our question is, why? What can be done to resolve this disparity?"

The model demonstrates how the length of nanotubes and the friction between them are the best indicators of overall fiber strength, and suggests strategies toward making them better. One is to simply use longer nanotubes. Another is to increase the number of crosslinks between the tubes, either chemically or by electron irradiation to create defects that make carbon atoms available to bond.

The coarse-grained model quantifies the friction between nanotubes, specifically how it regulates slip when the fibers are under strain and how well connections between nanotubes are likely to recover after breaking. The balance between length and friction is important: The longer the nanotubes, the fewer crosslinks are needed, and vice versa.

"Lengthwise gaps are just a function of how long you can make the nanotubes," Penev said. "These gaps are essentially defects that cause the interfaces to slip when you start pulling on a bundle."

With that inherent weakness as a given, Penev and lead author Nitant Gupta, a Rice graduate student, began to look at the impact of crosslinks on strength. "We modeled the links as carbon dimers or short hydrocarbon chains, and when we started pulling them, we saw they would stretch and break," Penev said.

"What became clear was that the overall strength of this interface depends a lot on the capability of these crosslinks to heal," he said. "If they break and reconnect to the next available carbon as the nanotubes slip, there will be an effective friction between the tubes that makes the fiber stronger. That's the ideal case."

"We show the crosslink density and the length play similar roles, and we use the product of these two values to characterize the strength of the whole bundle," Gupta said, noting the model is available for download via the paper's supporting information.

Penev said braiding nanotubes or linking them like chains would also likely strengthen fibers. Those techniques are beyond the capabilities of the current model, but worth studying, he said.

Yakobson said there's great technological value in strengthening materials. "It's an ongoing, uphill battle in labs around the world, with every advance in GPa (gigapascal, a measure of tensile strength) a great achievement.

"Our theory puts numerous disparate data in clearer perspective, highlighting that there's still a long way to the summit of strength while also suggesting specific steps to experimenters," he said. "Or so we hope."

INFORMATION:

Rice alumnus John Alred, now a technologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, is co-author of the paper. Yakobson is the Karl F. Hasselmann Professor of Materials Science and NanoEngineering and a professor of chemistry at Rice.

The Air Force Office of Scientific Research and computer resources via the National Science Foundation and Rice supported the research.

Read the abstract at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.0c08588.

This news release can be found online at https://news.rice.edu/2021/01/19/a-little-friction-goes-a-long-way-toward-stronger-nanotube-fibers/

Additional Contact

Mike Williams

713-348-6728

mikewilliams@rice.edu

Follow Rice News and Media Relations via Twitter @RiceUNews.

Related materials:

Yakobson Research Group:

https://biygroup.blogs.rice.edu

Rice Department of Materials Science and Nanoengineering:

https://msne.rice.edu

George R. Brown School of Engineering:

https://engineering.rice.edu

Images for download:

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/01/0119_STRENGTH-1-WEB.jpg

Rice University researchers modeled the relationship between the length of carbon nanotubes and the friction-causing crosslinks between them in a fiber and found the ratio can be used to measure the fiber's strength.

(Credit: Evgeni Penev/Rice University)

https://news-network.rice.edu/news/files/2021/01/0119_STRENGTH-2-WEB.jpg

Crosslinks between carbon nanotubes in a bundle are just as important as the length of the tubes to the overall fiber's strength, according to researchers at Rice University who built a computational model of the phenomenon.

(Credit: Evgeni Penev/Rice University)

Located on a 300-acre forested campus in Houston, Rice University is consistently ranked among the nation's top 20 universities by U.S. News & World Report. Rice has highly respected schools of Architecture, Business, Continuing Studies, Engineering, Humanities, Music, Natural Sciences and Social Sciences and is home to the Baker Institute for Public Policy. With 3,978 undergraduates and 3,192 graduate students, Rice's undergraduate student-to-faculty ratio is just under 6-to-1. Its residential college system builds close-knit communities and lifelong friendships, just one reason why Rice is ranked No. 1 for lots of race/class interaction and No. 1 for quality of life by the Princeton Review. Rice is also rated as a best value among private universities by Kiplinger's Personal Finance.

Scleroderma, a chronic and currently incurable orphan disease where tissue injury causes potentially lethal skin and lung scarring, remains poorly understood.

However, the defining characteristic of systemic sclerosis, the most serious form of scleroderma, is irreversible and progressive scarring that affects the skin and internal organs.

Published in iScience, Michigan Medicine's Scleroderma Program and the rheumatology and dermatology departments partnered with the Northwestern Scleroderma Program in Chicago and Mayo Clinic to investigate the causes of ...

Researchers have revealed the first atomic structures of the respiratory apparatus that plants use to generate energy, according to a study published today in eLife.

The 3D structures of these large protein assemblies - the first described for any plant species - are a step towards being able to develop improved herbicides that target plant respiration. They could also aid the development of more effective pesticides, which target the pest's metabolism while avoiding harm to crops.

Most organisms use respiration to harvest energy from food. Plants use photosynthesis to convert sunlight into sugars, and then respiration to break down the sugars into energy. This involves tiny cell components called mitochondria and a set of five protein assemblies ...

Provincial and territorial governments should set clear rules for vaccinating health care workers against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in public and private settings, and should not leave this task to employers, according to an analysis in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

"An effective vaccine provided to health care workers will protect both the health workforce and patients, reducing the overall burden of COVID-19 on services and ensuring adequate personnel to administer to people's health needs through the pandemic," writes Dr. Colleen M. Flood, University of Ottawa Research Chair in Health Law & Policy and a ...

HAMILTON, ON, Jan. 19, 2021 -- McMaster researchers have developed a new form of cultivated meat using a method that promises more natural flavour and texture than other alternatives to traditional meat from animals.

Researchers Ravi Selvaganapathy and Alireza Shahin-Shamsabadi, both of the university's School of Biomedical Engineering, have devised a way to make meat by stacking thin sheets of cultivated muscle and fat cells grown together in a lab setting. The technique is adapted from a method used to grow tissue for human transplants.

The sheets of living cells, each about the thickness of a sheet of printer paper, are first grown in culture and then concentrated on growth plates before being peeled ...

NANOTECHNOLOGY PREVENTS PREMATURE BIRTH IN MOUSE STUDIES

Media Contact: Rachel Butch, rbutch1@jhmi.edu

In a study in mice and human cells, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers say that they have developed a tiny, yet effective method for preventing premature birth. The vaginally delivered treatment contains nanosized (billionth of a meter) particles of drugs that easily penetrate the vaginal wall to reach the uterine muscles and prevent them from contracting. If proven effective in humans, the treatment could be one of the only clinical options available to prevent ...

From a pair of simple principles of evolution--chance mutation and natural selection--nature has constructed an almost unfathomable richness of life around us. Despite our scientific sophistication, human design and engineering have struggled to emulate nature's techniques and her inexhaustible inventiveness. But that may be changing.

In a new perspective article, Stephanie Forrest and Risto Miikkulainen explore a domain known as evolutionary computation (EC), in which aspects of Darwinian evolution are simulated in computer systems.

The study highlights the progress our machines have made in replicating evolutionary processes and what this could mean for engineering design, software refinement, gaming strategy, robotics and even medicine, while fostering a deeper insight ...

Using cutting-edge DNA sequencing technologies, a group of laboratories in Konstanz, Würzburg, Hamburg and Vienna, led by evolutionary biologist Professor Axel Meyer from the University of Konstanz, succeeded in fully sequencing the genome of the Australian lungfish. The genome, with a total size of more than 43 billion DNA building blocks, is nearly 14 times larger than that of humans and the largest animal genome sequenced to date. Its analysis provides valuable insights into the genetic and developmental evolutionary innovations that made it possible for fish to colonize land. The findings, published online in the journal Nature, expand our understanding of this major evolutionary ...

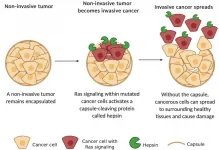

Researchers at the University of Helsinki have defined a cancer invasion machinery, which is orchestrated by a frequently mutated cancer gene called Ras. When signaling from Ras protein becomes abnormally high, like it does in many cancers, this switches on the cellular machinery that helps the cancer cells to depart from the tissue from which the cells have developed.

It has been unclear how the cancer invasion machinery works exactly, until now, as the study finds Ras in the role of Friar Lawrence in Shakespeare's famous play, "Get me an iron crow and bring it straight unto my cell (Romeo and Juliet, 5.2.21-23)." ...

Climate change is more pronounced in the Arctic than anywhere else on the planet, raising concerns about the ability of wildlife to cope with the new conditions. A new study shows that rare insects are declining, suggesting that climatic changes may favour common species.

As part of a new volume of studies on the global insect decline, researchers are presenting the first Arctic insect population trends from a 24-year monitoring record of standardized insect abundance data from North-East Greenland.

The work took place during 1996-2018 as part of the ecosystem-based monitoring program Greenland Ecosystem Monitoring at the field station Zackenberg, located in the world's largest national ...

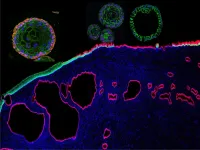

Organoids are increasingly being used in biomedical research. These are organ-like structures created in the laboratory that are only a few millimetres in size. Organoids can be used to study life processes and the effect of drugs. Because they closely resemble real organs, they offer several advantages over other cell cultures.

Now there are also organoid models developed for the cervix. This part of the female body is particularly at risk to develop cancers. By creating novel organoid models, a group led by Cindrilla Chumduri (Würzburg), Rajendra Kumar Gurumurthy (Berlin) and Thomas F. Meyer ...