Acidification impedes shell development of plankton off the US West Coast

2021-01-19

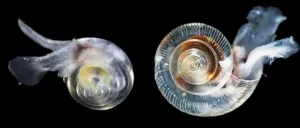

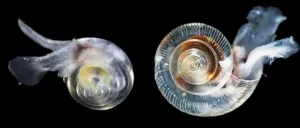

(Press-News.org) Shelled pteropods, microscopic free-swimming sea snails, are widely regarded as indicators for ocean acidification because research has shown that their fragile shells are vulnerable to increasing ocean acidity.

A new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, shows that pteropods sampled off the coasts of Washington and Oregon made thinner shells than those in offshore waters. Along the coast, upwelling from deeper water layers brings cold, carbon dioxide-rich waters of relatively low pH to the surface. The research, by a team of Dutch and American scientists, found that the shells of pteropods collected in this upwelling region were 37 percent thinner than ones collected offshore.

Sometimes called sea butterflies because of how they appear to flap their "wings" as they swim through the water column, fat-rich pteropods are an important food source for organisms ranging from other plankton to juvenile salmon to whales. They make shells by fixing calcium carbonate in ocean water to form an exoskeleton.

"It appears that pteropods make thinner shells where upwelling brings water that is colder and lower in pH to the surface, " said lead author Lisette Mekkes of Naturalis Biodiversity Centers and the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Mekkes added that while some shells also showed signs of dissolution, the change in shell thickness was particularly pronounced, demonstrating that acidified water interfered with pteropods' ability to build their shells.

The scientists examined shells of pteropods collected during the 2016 NOAA Ocean Acidification Program research cruise in the northern California Current Ecosystem onboard the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown. Shell thicknesses of 80 of the tiny creatures - no larger than the head of a pin - were analyzed using 3D scans provided by micron-scale computer tomography, a high-resolution X-ray technique. The scientists also examined the shells with a scanning electron microscope to assess if thinner shells were a result of dissolution. They also used DNA analysis to make sure the examined specimens belonged to a single population.

"Pteropod shells protect against predation and infection, but making thinner shells could also be an adaptive or acclimation strategy," said Katja Peijnenburg, group leader at Naturalis Biodiversity Center. "However, an important question is how long can pteropods continue making thinner shells in rapidly acidifying waters?"

The California Current Ecosystem along the West Coast is especially vulnerable to ocean acidification because it not only absorbs carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, but is also bathed by seasonal upwelling of carbon-dioxide rich waters from the deep ocean. In recent years these waters have grown increasingly corrosive as a result of the increasing amounts of atmospheric carbon dioxide absorbed into the ocean.

"Our research shows that within two to three months, pteropods transported by currents from the open-ocean to more corrosive nearshore waters have difficulty building their shells," said Nina Bednarsek, a research scientist from the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project in Costa Mesa, California, a coauthor of the study.

Over the last two-and-a-half centuries, scientists say, the global ocean has absorbed approximately 620 billion tons of carbon dioxide from emissions released into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels, changes in land-use, and cement production, resulting in a process called ocean acidification.

"The new research provides the foundation for understanding how pteropods and other microscopic organisms are actively affected by progressing ocean acidification and how these changes can impact the global carbon cycle and ecological communities," said Richard Feely, NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and chief scientist for the cruise.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by NOAA's Ocean Acidification Program.

Watch this video to get a sense of how fragile and tiny these creatures are: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L1-4gGTk3OM&feature=emb_logo

For more information, contact Theo Stein, NOAA Communications, at theo.stein@noaa.gov.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-19

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory and collaborators at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Alabama at Birmingham have discovered a new light-induced switch that twists the crystal lattice of the material, switching on a giant electron current that appears to be nearly dissipationless. The discovery was made in a category of topological materials that holds great promise for spintronics, topological effect transistors, and quantum computing.

Weyl and Dirac semimetals can host exotic, nearly dissipationless, electron conduction properties that take advantage of the unique state in the crystal lattice and electronic structure of the material that protects the electrons from doing so. These anomalous electron transport channels, ...

2021-01-19

Scientists have shown that two species of seasonal human coronavirus related to SARS-CoV-2 can evolve in certain proteins to escape recognition by the immune system, according to a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that, if SARS-CoV-2 evolves in the same way, current vaccines against the virus may become outdated, requiring new ones to be made to match future strains.

When a person is infected by a virus or vaccinated against it, immune cells in their body will produce antibodies that can recognise and bind to unique proteins on the virus' surface known as antigens. The immune system relies on being able to 'remember' the antigens that relate to a specific virus in order to provide immunity against it. However, in some viruses, such as ...

2021-01-19

DENVER--A study in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology (JTO) comparing surgeries performed at one Chinese hospital in 2019 with a similar date range during the COVID-19 pandemic found that routine thoracic surgery and invasive examinations were performed safely. The JTO is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Wentao Fang, MD, chief director of the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China and his colleagues analyzed the number of elective procedures ...

2021-01-19

Scientists are urging global policymakers and funders to think of fish as a solution to food insecurity and malnutrition, and not just as a natural resource that provides income and livelihoods, in a newly-published paper in the peer-reviewed journal Ambio. Titled "Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding," the paper argues for viewing fish from a food systems perspective to broaden the conversation on food and nutrition security and equity, especially as global food systems will face increasing threats from climate change.

The "Fish as Food" paper, authored by scientists and policy experts from Michigan State University, Duke ...

2021-01-19

HOUSTON - (Jan. 19, 2021) - Microscopic bubbles can tell stories about Earth's biggest volcanic eruptions and geoscientists from Rice University and the University of Texas at Austin have discovered some of those stories are written in nanoparticles.

In an open-access study published online in Nature Communications, Rice's Sahand Hajimirza and Helge Gonnermann and UT Austin's James Gardner answered a longstanding question about explosive volcanic eruptions like the ones at Mount St. Helens in 1980, the Philippines' Mount Pinatubo in 1991 or Chile's Mount Chaitén in 2008.

Geoscientists have long sought to use tiny bubbles in erupted lava and ash to reconstruct some of the conditions, ...

2021-01-19

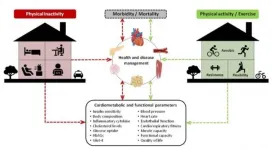

Social distancing and working from home help prevent transmission of the novel coronavirus but can be conducive to unhealthy behavior such as bingeing on fast food or spending more time in a chair or on a couch staring at a screen, and generally moving about less during the day. Scientists believe the reduction in physical activity experienced during the first few months of the pandemic could lead to an annual increase of more than 11.1 million in new cases of type 2 diabetes and result in more than 1.7 million deaths.

The estimates are presented by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP), Brazil, in a review article published in Frontiers in Endocrinology. The authors stress that there is an "urgent need" to recommend physical activity during ...

2021-01-19

Just how close are the world's countries to achieving the Paris Agreement target of keeping climate change limited to a 1.5°C increase above pre-industrial levels?

It's a tricky question with a complex answer. One approach is to use the remaining carbon budget to gauge how many more tonnes of carbon dioxide we can still emit and have a chance of staying under the target laid out by the 2015 international accord. However, estimates of the remaining carbon budget have varied considerably in previous studies because of inconsistent approaches and assumptions used by researchers.

Nature Communications Earth and Environment just published a paper by a group of researchers led by Damon Matthews, professor in the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment. In it, ...

2021-01-19

TAMPA, Fla. - Cells need energy to survive and thrive. Generally, if oxygen is available, cells will oxidize glucose to carbon dioxide, which is very efficient, much like burning gasoline in your car. However, even in the presence of adequate oxygen, many malignant cells choose instead to ferment glucose to lactic acid, which is a much less efficient process. This metabolic adaptation is referred to as the Warburg Effect, as it was first described by Otto Warburg almost a century ago. Ever since, the conditions that would evolutionarily select for cells to exhibit a Warburg Effect have been in debate, as it is much less efficient and produces toxic waste ...

2021-01-19

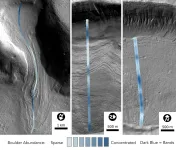

In a new paper published today in the Proceedings of the National Academies of ScienceS (PNAS), planetary geologist Joe Levy, assistant professor of geology at Colgate University, reveals a groundbreaking new analysis of the mysterious glaciers of Mars.

On Earth, glaciers covered wide swaths of the planet during the last Ice Age, which reached its peak about 20,000 years ago, before receding to the poles and leaving behind the rocks they pushed behind. On Mars, however, the glaciers never left, remaining frozen on the Red Planet's cold surface for more than 300 million years, covered in debris. "All the rocks and sand carried on that ice have remained ...

2021-01-19

ATLANTA--Early in the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment claims were largely driven by state shutdown orders and the nature of a state's economy and not by the virus, according a new article by Georgia State University economists.

David Sjoquist and Laura Wheeler found no evidence the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) affected the number of initial claims during the first six weeks of the pandemic.

Their research explores state differences in the magnitude of weekly unemployment insurance claims for the weeks ending March 14 through April 25 by focusing on three factors: the impact of COVID-19, the effects of state economic structures and state orders closing non-essential ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Acidification impedes shell development of plankton off the US West Coast