(Press-News.org) In a large-scale study of Danish children and young people, researchers from Aarhus University have for the first time found genetic variants that increase the risk of nocturnal enuresis - commonly known as bedwetting or nighttime incontinence. The findings provide completely new insights into the processes in the body causing this widespread phenomenon.

Researchers have long known that nighttime incontinence is a highly heritable condition. Children who wet the bed at night often have siblings or parents who either suffer from or have suffered from the same condition. But until now, science has been unable to pinpoint the genes concerned.

In collaboration with the Danish research project iPSYCH and a team of international colleagues, researchers from Aarhus University have for the first time identified genetic variants that increase the risk of bedwetting. The results have just been published in the scientific journal The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

"As many as sixteen per cent of all seven-year-olds suffer from nocturnal enuresis and although many of them grow out of it, one to two per cent of all young adults still have this problem. It is a serious condition, which can negatively affect children's self-esteem and well-being. For example, the children may be afraid of being bullied, and often opt out of events that involve overnight stays," says Jane Hvarregaard Christensen, who is one of the researchers behind the study.

Regulates urine production

In the study, the researchers studied the genes of 3,900 Danish children and young people, who had either been diagnosed with nocturnal enuresis or had taken medication for it. This group was subsequently compared to 31,000 children and young people who did not suffer from the problem.

"We identified two locations in the genome where specific genetic variants increase the risk of bedwetting. The potential causal genes which we point to play roles in relation to ensuring that our brain develops the ability to keep urine production down at night, that the bladder's activity is regulated and registered, and that we sleep in an appropriate way, among other things," explains first author of the study, Cecilie Siggaard Jørgensen.

The study also shows that commonly occurring genetic variants can explain up to one-third of the genetic risk of bedwetting. This means that genetic variants which all of us have may lead to involuntary nocturnal enuresis, when they occur in a certain combination.

"But you can still also have all the variants without wetting the bed at night, because there are other risk factors in play that we haven't mapped yet - both genetic and environmental. So it's clear that this is very complex and that it's not possible to talk about a single gene that causes nocturnal enuresis," says Jane Hvarregaard Christensen.

Particularly vulnerable

The study also shows that children with many genetic variants that increase the risk of ADHD are particularly vulnerable to developing bedwetting.

"Our findings don't mean that ADHD causes bedwetting in a child, or vice versa, but just that the two conditions have common genetic causes. More research in this area will be able to clarify the details in the biological differences and similarities between the two disorders," she emphasises.

As the study is a first-time study, the researchers also examined more than 5,500 people from Iceland, where they found that the same genetic variants also appear to increase the risk of nocturnal enuresis.

"This means that we can be more certain that our findings are not coincidental. In the future, we wish to find out whether the same genetic variants increase the risk of bedwetting in children in other parts of the world. Bedwetting is not just an issue in northern European but affects millions of children all over the world," she says.

The researchers hope to be able to further clarify the causes of nocturnal enuresis. It is very likely that it will be possible to identify even more genes and thereby gain a deeper understanding of what is required for a child to become dry at night.

"At present we still can't use a child's genetic profile to predict, for example, whether the child will grow out of its condition or whether a particular treatment works. Perhaps this will be possible in the future when more detailed studies have been conducted," says Jane Hvarregaard Christensen.

Behind the results

The study is a so-called genome-wide association study (GWAS). By examining thousands of genetic variants spread out in the entire genome, a GWAS makes it possible to point to statistically significant correlations between specific genetic variants and nighttime incontinence in the persons who are examined.

INFORMATION:

The study is a collaboration between researchers at the Department of Biomedicine, Aarhus University and the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital. Researchers from the Lundbeck Foundation Initiative for Integrative Psychiatric Research, iPSYCH, and deCODE genetics have also contributed.

The study is financed by the Lundbeck Foundation and the Stanley Foundation.

The scientific article can be read in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health

Contact

PhD Student Cecilie Siggaard Jørgensen

Aarhus University, Department of Clinical Medicine and

Aarhus University Hospital - Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine

cecilie.siggaard@clin.au.dk

+45 61161606

Professor Søren Rittig

Aarhus University, Department of Clinical Medicine and

Aarhus University Hospital - Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine

rittig@clin.au.dk

+45 2024 1005

Project Manager, Associate Professor Jane Hvarregaard Christensen

Jane Hvarregaard Christensen

Aarhus University, Department of Biomedicine

jhc@biomed.au.dk

+45 9352 2003

Shelled pteropods, microscopic free-swimming sea snails, are widely regarded as indicators for ocean acidification because research has shown that their fragile shells are vulnerable to increasing ocean acidity.

A new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, shows that pteropods sampled off the coasts of Washington and Oregon made thinner shells than those in offshore waters. Along the coast, upwelling from deeper water layers brings cold, carbon dioxide-rich waters of relatively low pH to the surface. The research, by a team of Dutch and American scientists, ...

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory and collaborators at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Alabama at Birmingham have discovered a new light-induced switch that twists the crystal lattice of the material, switching on a giant electron current that appears to be nearly dissipationless. The discovery was made in a category of topological materials that holds great promise for spintronics, topological effect transistors, and quantum computing.

Weyl and Dirac semimetals can host exotic, nearly dissipationless, electron conduction properties that take advantage of the unique state in the crystal lattice and electronic structure of the material that protects the electrons from doing so. These anomalous electron transport channels, ...

Scientists have shown that two species of seasonal human coronavirus related to SARS-CoV-2 can evolve in certain proteins to escape recognition by the immune system, according to a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that, if SARS-CoV-2 evolves in the same way, current vaccines against the virus may become outdated, requiring new ones to be made to match future strains.

When a person is infected by a virus or vaccinated against it, immune cells in their body will produce antibodies that can recognise and bind to unique proteins on the virus' surface known as antigens. The immune system relies on being able to 'remember' the antigens that relate to a specific virus in order to provide immunity against it. However, in some viruses, such as ...

DENVER--A study in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology (JTO) comparing surgeries performed at one Chinese hospital in 2019 with a similar date range during the COVID-19 pandemic found that routine thoracic surgery and invasive examinations were performed safely. The JTO is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Wentao Fang, MD, chief director of the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China and his colleagues analyzed the number of elective procedures ...

Scientists are urging global policymakers and funders to think of fish as a solution to food insecurity and malnutrition, and not just as a natural resource that provides income and livelihoods, in a newly-published paper in the peer-reviewed journal Ambio. Titled "Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding," the paper argues for viewing fish from a food systems perspective to broaden the conversation on food and nutrition security and equity, especially as global food systems will face increasing threats from climate change.

The "Fish as Food" paper, authored by scientists and policy experts from Michigan State University, Duke ...

HOUSTON - (Jan. 19, 2021) - Microscopic bubbles can tell stories about Earth's biggest volcanic eruptions and geoscientists from Rice University and the University of Texas at Austin have discovered some of those stories are written in nanoparticles.

In an open-access study published online in Nature Communications, Rice's Sahand Hajimirza and Helge Gonnermann and UT Austin's James Gardner answered a longstanding question about explosive volcanic eruptions like the ones at Mount St. Helens in 1980, the Philippines' Mount Pinatubo in 1991 or Chile's Mount Chaitén in 2008.

Geoscientists have long sought to use tiny bubbles in erupted lava and ash to reconstruct some of the conditions, ...

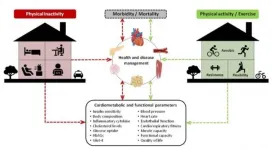

Social distancing and working from home help prevent transmission of the novel coronavirus but can be conducive to unhealthy behavior such as bingeing on fast food or spending more time in a chair or on a couch staring at a screen, and generally moving about less during the day. Scientists believe the reduction in physical activity experienced during the first few months of the pandemic could lead to an annual increase of more than 11.1 million in new cases of type 2 diabetes and result in more than 1.7 million deaths.

The estimates are presented by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP), Brazil, in a review article published in Frontiers in Endocrinology. The authors stress that there is an "urgent need" to recommend physical activity during ...

Just how close are the world's countries to achieving the Paris Agreement target of keeping climate change limited to a 1.5°C increase above pre-industrial levels?

It's a tricky question with a complex answer. One approach is to use the remaining carbon budget to gauge how many more tonnes of carbon dioxide we can still emit and have a chance of staying under the target laid out by the 2015 international accord. However, estimates of the remaining carbon budget have varied considerably in previous studies because of inconsistent approaches and assumptions used by researchers.

Nature Communications Earth and Environment just published a paper by a group of researchers led by Damon Matthews, professor in the Department of Geography, Planning and Environment. In it, ...

TAMPA, Fla. - Cells need energy to survive and thrive. Generally, if oxygen is available, cells will oxidize glucose to carbon dioxide, which is very efficient, much like burning gasoline in your car. However, even in the presence of adequate oxygen, many malignant cells choose instead to ferment glucose to lactic acid, which is a much less efficient process. This metabolic adaptation is referred to as the Warburg Effect, as it was first described by Otto Warburg almost a century ago. Ever since, the conditions that would evolutionarily select for cells to exhibit a Warburg Effect have been in debate, as it is much less efficient and produces toxic waste ...

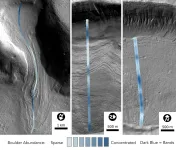

In a new paper published today in the Proceedings of the National Academies of ScienceS (PNAS), planetary geologist Joe Levy, assistant professor of geology at Colgate University, reveals a groundbreaking new analysis of the mysterious glaciers of Mars.

On Earth, glaciers covered wide swaths of the planet during the last Ice Age, which reached its peak about 20,000 years ago, before receding to the poles and leaving behind the rocks they pushed behind. On Mars, however, the glaciers never left, remaining frozen on the Red Planet's cold surface for more than 300 million years, covered in debris. "All the rocks and sand carried on that ice have remained ...