Electron transfer discovery is a step toward viable grid-scale batteries

2021-01-21

(Press-News.org) The liquid electrolytes in flow batteries provide a bridge to help carry electrons into electrodes, and that changes how chemical engineers think about efficiency.

The way to boost electron transfer in grid-scale batteries is different than researchers had believed, a new study from the University of Michigan has shown.

The findings are a step toward being able to store renewable energy more efficiently.

As governments and utilities around the world roll out intermittent renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, we remain reliant on coal, natural gas and nuclear power plants to provide energy when the wind isn't blowing and the sun isn't shining. Grid-scale "flow" batteries are one proposed solution, storing energy for later use. But because they aren't very efficient, they need to be large and expensive.

In a flow battery, the energy is stored in a pair of "electrolyte" fluids which are kept in tanks and flow through the working part of the battery to store or release energy. An active metal gains or loses electrons from the electrode on either side, depending on whether the battery is charging or discharging. One efficiency bottleneck is how quickly electrons move between the electrodes and the active metal.

"By maximizing the charge transfer, we can reduce the overall cost of flow batteries," said study first author Harsh Agarwal, a chemical engineering Ph.D. student who works in the lab of Nirala Singh, U-M assistant professor of chemical engineering.

Researchers have been trying different chemical combinations to improve it, but they don't really know what's going on at the molecular level. This study, published in Cell Reports Physical Science, is one of the first to explore it.

Researchers had believed that the negatively charged molecular groups from the acids provided more spots for electron transfer to take place on the battery's negative electrode. The findings from the team co-led by Singh and Bryan Goldsmith, the Dow Corning Assistant Professor of Chemical Engineering, tell a different story. Instead, the acid groups lowered the energy barrier of the electron transfer by serving as a sort of bridge between the active metal in the fluid--vanadium in this case--and the electrode. This helps the vanadium give up its electron.

"Our findings suggest that bridging may play a critical yet underexplored role in other flow battery chemistries employing transition metals," Singh said. "This discovery is not only relevant to energy storage but also fields of corrosion and electrodeposition."

The study shows that the reaction rate in flow batteries can be tuned by controlling how well the acid in the liquid electrolyte binds with the active metal.

"Researchers can apply this knowledge to electrolyte engineering or electrocatalyst development, both of which are important disciplines in sustainable energy," Agarwal said.

Agarwal and Singh measured the reaction rate between the vanadium and electrode for five different acidic electrolytes. To get a clearer picture of the details at the atomic level, the team used a form of quantum mechanical modeling, known as density functional theory, to calculate how well the vanadium-acid combinations bind to the electrode. This part of the study was undertaken by Goldsmith and Jacob Florian, a chemical engineering senior undergraduate student working in the Goldsmith lab.

At Argonne National Laboratory, Agarwal and Singh used X-ray spectroscopy to discover details about how the vanadium ions configured themselves when in contact with different acids. Density functional theory calculations helped interpret the X-ray measurements. The study also provides the first direct experimental verification of how water attaches to vanadium ions.

INFORMATION:

Image: https://docs.google.com/document/d/12zhpF3xUMztkFTI8tnuQc5dCOdSTYr_D1onvUbsMNCk/edit

The study is titled "The effect of anion bridging on heterogeneous charge transfer for V2+/V3+." The work was supported by the University of Michigan Office of Research. This research used the resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, Argonne National Laboratory and the Canadian Light Source.

Nirala Singh

Bryan Goldsmith

Abstract of paper

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-21

New Rochelle, NY, January 20, 2020--SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, blocks the processes of innate immune activation that normally direct the production and/or signaling of type I interferon (IFN-I) by the infected cell and tissues. IFN-I is a key component of host innate immunity that is responsible for eliminating the virus at the early stage of infection, as summarized in a recent review article in Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research (JICR). By suppressing innate immunity, the virus replicates and spreads in the body unchecked, leading to the disease known as COVID-19. Click here to read the article now.

"SARS-CoV-2 utilizes various approaches to evade host IFN-I response, including suppression of IFN-I ...

2021-01-21

Even a modest sea level rise, triggered by increasing global temperatures, would place 100 airports below mean sea level by 2100, a new study has found.

Scientists from Newcastle University modelled the risk of disruption to flight routes as a result of increasing flood risk from sea level rise.

Publishing the findings in the journal Climate Risk Management, Professor Richard Dawson and Aaron Yesudian of Newcastle University's School of Engineering analysed the location of more than 14,000 airports around the world and their exposure to storm surges for current and future sea level. The researchers also studied airports' pre-COVID-19 connectivity and aircraft traffic, and their current level of flood protection.

They ...

2021-01-21

A brain pressure disorder that especially affects women, causing severe headaches and sometimes permanent sight loss, has risen six-fold in 15 years, and is linked to obesity and deprivation, a new study by Swansea University researchers has shown.

Rates of emergency hospital admissions in Wales for people with the disorder were also five times higher than for those without.

The condition is called idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). It causes increased pressure in the fluid surrounding in the brain. This can lead to severely disabling headaches as well as vision loss, which ...

2021-01-21

Despite the anticounterfeiting devices attached to luxury handbags, marketable securities, and identification cards, counterfeit goods are on the rise. There is a demand for the next-generation anticounterfeiting technology - that surpasses the traditional ones - that are not easily forgeable and can hold various data.

A POSTECH research team, led by Professor Junsuk Rho of the departments of mechanical engineering and chemical engineering, Ph.D. candidates Chunghwan Jung of the Department of Chemical Engineering and Younghwan Yang of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, have together succeeded in making a switchable display device using nanostructures that is capable of encrypting full-color images depending on the polarization of light. These findings were recently published in ...

2021-01-21

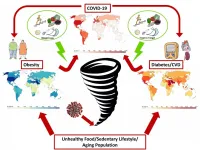

In a Nature Reviews Endocrinology article authors from the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD) highlight the interconnection of obesity and impaired metabolic health with the severity of COVID-19. First, they provide information about the independent relationships of obesity, disproportionate fat distribution and impaired metabolic health with the severity of COVID-19. Then they discuss mechanisms for a complicated course of COVID-19 and how this disease may impact on the global obesity and cardiometabolic pandemics. Finally, they provide recommendations for prevention and treatment in clinical practice and in the public health sector to combat these global pandemics.

Norbert Stefan, Andreas Birkenfeld and Matthias Schulze summarize ...

2021-01-21

Letters, syllables, words and sentences--spatially arranged sets of symbols that acquire meaning when we read them. But is there an area and cognitive mechanism in our brain that is specifically devoted to reading? Probably not; written language is too much of a recent invention for the brain to have developed structures specifically dedicated to it.

According to this novel paper published in Current Biology, underlying reading there is evolutionarily ancient function that is more generally used to process many other visual stimuli. To prove it, SISSA ...

2021-01-21

Research led by the universities of Kent and Oxford has found that fans of the least successful Premier League football teams have a stronger bond with fellow fans and are more 'fused' with their club than supporters of the most successful teams.

The study, which was carried out in 2014, found that fans of Crystal Palace, Hull, Norwich, Sunderland, and West Bromwich Albion were found to have higher loyalty towards one another and even expressed greater willingness to sacrifice their own lives to save the lives of other fans of their club. This willingness was much higher than that of Manchester United, Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool or Manchester City fans. A decade of club statistics from 2003-2013 was used to identify the ...

2021-01-21

Schools are closing again in response to surging levels of COVID-19 infection, but staging randomised trials when students eventually return could help to clarify uncertainties around when we should send children back to the classroom, according to a new study.

Experts say that school reopening policies currently lack a rigorous evidence base - leading to wide variation in policies around the world, but staging cluster randomized trials (CRT) would create a body of evidence to help policy makers take the right decisions.

The pandemic's rapid ...

2021-01-21

Despite being the subject of increasing interest for a whole century, how preeclampsia develops has been unclear - until now.

Researchers believe that they have now found a primary cause of preeclampsia.

"We've found a missing piece to the puzzle. Cholesterol crystals are the key and we're the first to bring this to light," says researcher Gabriela Silva.

Silva works at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) Centre of Molecular Inflammation Research (CEMIR), a Centre of Excellence, where she is part of a research group for inflammation in pregnancy led by Professor Ann-Charlotte Iversen.

The findings are good news for the approximately three per cent of pregnant ...

2021-01-21

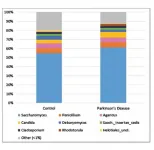

Amsterdam, NL, January 21, 2021 - The bacterial gut microbiome is strongly associated with Parkinson's disease (PD), but no studies had previously investigated he role of fungi in the gut. In this novel study published in the Journal of Parkinson's Disease, a team of investigators at the University of British Columbia examined whether the fungal constituents of the gut microbiome are associated with PD. Their research indicated that gut fungi are not a contributing factor, thereby refuting the need for any potential anti-fungal treatments of the gut in PD patients.

"Several studies conducted since 2014 have characterized changes in the gut microbiome," explained lead investigator Silke Appel-Cresswell, MD, Pacific Parkinson's Research Centre and Djavad ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Electron transfer discovery is a step toward viable grid-scale batteries